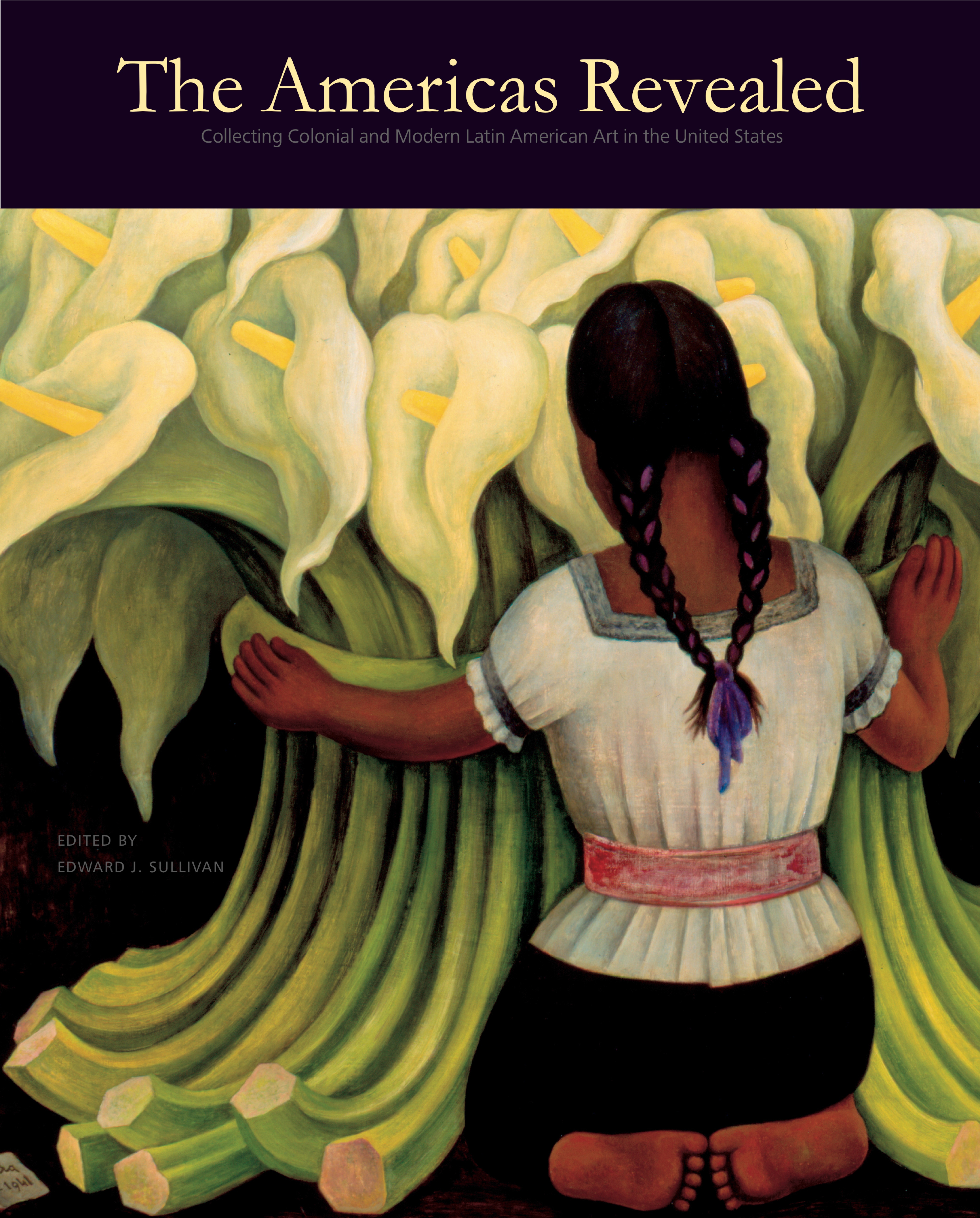

The Americas Revealed: Collecting Colonial and Modern Latin American Art in the United States

Edited by Edward J. Sullivan

Edited by Edward J. Sullivan

With essays by Miriam Margarita Basilio, Estrellita B. Brodsky, Vanessa K. Davidson, Anna Indych-López, Ronda Kasl, Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, Berit Potter, Mari Carmen Ramírez, Joseph Rishel, Delia Solomons, and Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt

University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press in association with The Frick Collection, 2018; 224 pp.; 48 color illus.; 16 b/w illus.; Hardcover: $69.95 (ISBN: 9780271079523)

Collecting is an activity that establishes hierarchies over time, creates meaning, and legitimizes ideological stances. In the same way, it is a cultural phenomenon that is directly associated with taste and personal obsessions and is often influenced by political factors. As described in this compilation of eleven essays coordinated by the distinguished art historian Edward J. Sullivan, the study of Latin American Art in the United States through both private and institutional collecting serves as a tool of analysis for the reinterpretation of Latin American artwork produced from the colonial period to the present day. Latin America is conceived of as a geopolitical region whose cultural and aesthetic differences need to be distinguished. In this way, the Kunstgeographie (meaning the geography of art), traces artistic and cultural exchanges and the distribution of concepts and contact zones. Collecting contributes in various ways to this map of artistic geography and allows the contributors to establish new parameters and categories for the circulation and reception of artworks.

In his introductory essay, “Acquisitive Passions: Observations on Collecting the Art of the Americas in the United States,” Sullivan surveys the history of Latin American collecting practices in North America, discussing its formation, individualities, and typologies. Key figures in this continental cultural exchange, such as Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, Lincoln Kirstein, Albert Bender, and René d’Harnoncourt, greatly determined the movement and final destination of works by Latin American artists throughout the United States. As Sullivan explains, the history of collecting is directly related to the history of exhibitions, which functioned as strategies of artistic promotion and also coincided with the reinforcement of cultural diplomacy between the United States and Latin America in two key moments of their shared history, namely the 1930s–1940s and the period of the Cold War. For this reason, a new way of understanding transnational bonds is presented here: Mexico and other Latin American countries were not isolated from North American artistic and cultural policies. Instead, the instrumentation of a conciliatory Pan-Americanism during the period of World War II resulted in a new understanding of the political climate that directly resulted in the formation of various notable American museum collections.

The eleven essays compiled in The Americas Revealed explain through different perspectives and approaches the practice of collecting Latin American Art in the United States. Their focus ranges from the political and private contexts for collecting to highlighting the ideologies of the collectors themselves. Contributions by art historians and curators explore methods of collecting and consider how Latin American art has been perceived at various points in this history. A notable aspect of this compendium is that it presents a more global approach, which avoids the construction of interpretations that can at times be exclusionary. Concepts of identity and territory can no longer be perceived in a singular way. The essays in this volume therefore hint at a more open scholarly dialogue with a broader scope that allows for more diverse voices. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that for researchers of Latin American art, this book represents an important contribution to the discipline because it refers to existing collections—complete, fragmented, or occasionally little known—that enable reflection upon local and international convergences, as well as the multiple parameters of so-called “national representations.”

The book is structured around case studies in the development of collections of Latin American art from the colonial, modern, and contemporary period that are thematically related. Essays by Miriam Margarita Basilio, Joseph Rishel, Berit Potter, and Vanessa K. Davidson illustrate the role of museums and the formation of archives of Latin American art in iconic institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, Philadelphia Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Phoenix Museum of Art. These museums are very well known for maintaining a long and historic connection with Latin American art and artists. In addition to the museums, contributors describe the exhibitions and the gradual acquisition of works overseen by both directors and curators that promoted the idea of Latin American art as innovative. As these essays outline, emphasis was increasingly placed upon the purchasing of paintings and prints by Mexican artists, and most importantly, these works were then included in public exhibitions. These authors demonstrate how the acquisition of works of art also reflected political agendas wherein museum trustees directly intervened in collecting practices. MoMA became the paradigm for this type of collecting, a model that has resulted in inevitable paradoxes of inclusion and exclusion.

Among the most enriching aspects of the book are the essays that address repositories of colonial works. Ronda Kasl considers the growing interest by both collectors and emblematic museums, such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, at the beginning of the twentieth century for works produced in New Spain, particularly ceramic objects (fig. 1). Such decorative arts objects were later exhibited in its galleries as a kind of extension of the European influence in Latin America, which required legitimization in its own territory. In her essay, Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt examines the collection of Roberta and Richard Huber that focuses on Spanish and Portuguese colonial art. The invaluable testimony of the Hubers sheds light on the personal experiences of contemporary collectors who compile objects with a sense of vocation and an eye toward the preservation of heritage. Likewise, Delia Solomons reviews the ways in which popular artistic styles that were widely accepted by the 1970s, a decade characterized by political and ideological confrontations, supported institutional collecting of Latin American art. As already mentioned, such collecting was promoted through strategies of exhibition employed by mainstream museums. Solomons explains that the acquisition of abstract work was simultaneous to the organization of groundbreaking exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum and MoMA, such as The Emergent Decade or The 1964 Guggenheim International (1965–67).

Lastly, Mari Carmen Ramírez discusses the curatorial practices of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), and discusses the acquisition of canonical artists who experienced greater success over others who have garnered less recognition. Ramírez provides details on the mechanisms of MFAH exhibitions and describes changing narratives regarding Latin American art that defined the growth of the museum collection.

The art historian James Oles wrote that a significant part of the history of Mexican art is found in the United States.1 This volume demonstrates the truth of such a declaration and reconsiders the international circulation of Mexican artwork from the 1920s and 1930s forward. The essay by Anna Indych-López transcends the stereotype of the “vogue for all things Mexican” in the early twentieth century, sparking an examination of the international modernist context that corresponded to the art market. Similarly, the texts by Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro and Estrellita B. Brodsky provide interpretations of the collecting of contemporary Latin American art from a global perspective. While Brodsky describes the role collectors have personally played in various institutions, Pérez-Barreiro observes how the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection attends to new forms of collecting, not because it belongs to a certain geographical region but instead because of its capacity to trigger new interpretations of different moments of Latin American art. In this way, both essays describe how individuals and collections have an important impact on research into contemporary Latin American movements.

Within the spirit of a transnational perspective, The Americas Revealed is among a group of recent comparative studies that engage with debates on the modernity of Latin American countries and the elements they share with other regions. Artistic modernity therefore can be illustrated through the dynamic tensions among spaces, people, time, and borders, all of which favor exchanges, networks, and intense flows of artistic migration, creating a weave that is traced in this book through the different paths forged by the practice of collecting.

In conclusion, the necessary internationalization of cultural borders has created artistic and cultural structures that allow the redefinition of the image of Latin America beyond a nationalist concept. The Americas Revealed clearly demonstrates how cultural, intellectual, and artistic relations between the United States and Latin America impact the development of collecting. In general terms, the objective of the book is to reflect upon and promote new scholarship addressing the transmission and appropriation of ideas, cultural objects, and images of Latin America in the United States. It is crucial to recognize the work done by The Frick Collection through the publication of a series of specialized books on art history and collecting, of which this book is the fourth volume. It is profusely and beautifully illustrated, and the bibliography serves as an updated reference, helping the reader to engage deeply with the topics addressed. It is undeniable that this book will become a great contribution for the classroom and an obligatory scholarly reference. There is, however, still much work to do. Above all, in this era, complex scholarship is needed that allows for an explanation of the arts of Latin America in rich and detailed ways.

Cite this article: Dafne Cruz Porchini, review of The Americas Revealed: Collecting Colonial and Modern Latin American Art in the United States, edited by Edward J. Sullivan, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1706.

PDF: Porchini, review of The Americas Revealed

Notes ↑

- James Oles, “Colecciones disueltas: sobre unos extranjeros y muchos cuadros mexicanos,” Patrocinio, colección y circulación de las artes. XX Coloquio Internacional de Historia del Arte (México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, 1997), 623. ↵

About the Author(s): Dafne Cruz Porchini is affiliated with the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas (Institute of Aesthetic Research), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México