Queer California: Untold Stories

Curated by: Christina Linden

Exhibition schedule: Oakland Museum of California, April 13–August 11, 2019

The exhibition Queer California: Untold Stories was conceived to address a principal concern: What gets left out of historical narratives about queer history? Historicizing, by its very nature, must consolidate events into what feels most essential. But essential to whom? Essential for whom? Curator Christina Linden set out to rejigger the narrative, privileging the untold accounts and the unseen communities throughout California. In some ways, it is an impossible task. How can one represent even a partial history of queerness in a state as large and storied as California? It goes without saying that the queer community has made remarkable strides in achieving greater social acceptance and has earned significant gains in the name of equality. But what about the individuals who do not see themselves in these victories? What about those individuals who do not really see themselves represented anywhere? Linden acknowledges that Queer California is not fully inclusive. Not only would this task be impossible, but we as viewers would not have time to absorb the result. Necessarily, this exhibition also carries the torch of history, but it is a decidedly fresh and future-gazing take.

Queer California is packed. Entering the Great Hall gallery of the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) means engagement with an active world. The space feels undersized, although one must wonder what space would be sufficient. Limits must be drawn somewhere. And so, like Alice passing into a new underworld, experiencing the exhibition is to enter an ebullient space brimming over with stories to tell. The stories are at times tender, funny, communalist, sexy, and yes, traumatic, too. But this exhibition is not relying on tragedy to tell its tales. The struggle, the fight, and the persisting oppression have been used countless times to insist on an urgency and appeal to the empathy of viewing audiences. While those concerns of queer life remain acute and pressing, Queer California declares that they are only one facet of complex, lived experiences.

Never Not Been a Part of Me, an OMCA-produced video created for Queer California, illustrates the guiding principle of the exhibition. This is not an artwork but instead takes the form of a collection of interviews with eight members of various Californian Native American tribes who identify as many things (such as Indigenous, Native language historian, individualistic, community member, singer, or outside of any category whatsoever), but among those identities is a connection to queerness. In the span of nineteen minutes, the video shows the complexities and complications of terms such as queer. That term originates from a settler colonial culture, as does the term heteronormative, and so for many of the individuals interviewed, queer does not fit their experience. “Two-spirit” has become an umbrella term used across native cultures to describe a sort of third gender. The designation was coined to distinguish from non-Native LGBTQ terminology and attends to more traditional cultural and ceremonial gender roles within Native communities. However, two-spirit does not speak to all identities. In fact, it does not come close. The video interviews individuals of varied ages and from different Indigenous communities around California, each grappling with terms such as two-spirit, queer, and the various other descriptors recovered by studying their respective Native languages. Labels are imperfect, and the video asserts the impossibility of a universal representation.

The curatorial concept for the exhibition comes through in the nonhierarchical, anti-patriarchal design, resulting in the absence of a predetermined way to navigate the presentation. Instead, small eddies of side galleries, nooks, and crannies are created to allow for wandering and discovery. Different worlds reveal themselves if you look, worlds such as that of gay men’s motorcycle clubs, black queer zines, or that of a working-class lesbian bar in Eastside Los Angeles. The exhibition has ample and generous seating throughout, but nowhere is the seating ordered as in an auditorium. There is also no consistent visual vocabulary; one screening room has staggered benches and another has small plush stools. The spaces are unregimented, and each is unique, as uniformity is not the objective.

The exhibition is polyphonic, with competing sounds emanating from all sides communicating that this is not a space for reverence. It is a place where diverse voices can be heard, and one need not observe the exhibition in silence. One such voice comes from a park bench, or in other areas of the exhibition a car seat, where oral histories of cruising Balboa Park in San Diego can be heard from a sound shower above (fig. 1). The work, Queen’s Circle (2016/19), by Parkeology, reveals stories of socializing and cruising told through the memories of drag queens, dykes, madames, healthcare workers, leather daddies, police officers, politicians, park rangers, and others.

Another element contributing to the chorus of Queer California is an installation, Trans Hirstories of the Bay Area, staged by the Museum of Trans History and Art (MOTHA.) Founded in 2013 by its current director, Chris E. Vargas, MOTHA exists as a museum without walls and is physically manifested through context-specific projects. In this exhibition, Trans Hirstories of the Bay Area is a collection of artwork, artifacts, oral histories, music, and ephemera dedicated to the cultural work of trans artists, hirstorians (an anti-patriarchal term that Vargas uses in lieu of historian), activists, community members, and scholars. All of this material is housed within a small freestanding gallery that serves as a museum within a museum. The installation seems to focus largely on people of color within the trans community, and the stories tell of community and chosen families with a palpable kindheartedness. Of particular note is the work of Jerome Caja, whose untitled checkerboard, from about 1990, makes checkers out of bottlecaps with a little pig, or TV, or cock, or syringe painted in nail polish. Above it are two framed Caja works: Ascension of the Drag Queen (1994; SFMOMA), also painted in nail polish, showing a cheeky ascension scene where the ascending figure is a drag queen being lifted up by two little putti who happen to be clowns; and The Ascension of the Fruit Bowl (1991; SFMOMA) depicting a winged nude man lifting a bowl of fruit over a burning city. These charming and peculiar works are viewed near a speaker playing a 1978 disco hit, “You Make Me Feel,” by Sylvester. The soundtrack escapes to most areas of the gallery, setting a playful tone for the entire exhibition.

Appropriately, Queer California is not all merriment and good times. A small gallery of work by Cassils shows documentation of a performance made in response to the violence against trans and gender-nonconforming people. Cassils uses their own body in a sculptural manner, undergoing rigorous fitness routines to sculpt their own transmasculine physique. The performance, Becoming an Image (2012–present), represented in photographs, shows the artist physically fighting with a one-ton block of clay. Cassils wrestles, kicks, and punches the block while naked in total darkness. The struggle took place before an audience who could only see the action through the illumination of a camera flash. One need not be present for the performance to feel the immense strain of effort, representing both frustration and catharsis at once. Also present in the space is a bronze casting of the enormous manipulated clay block after the performance. The bronzed sculpture benefits from being touchable. Visitors to the exhibition can physically feel the impact of the performance, and the act of reaching out to touch and feel it is inherently an empathetic gesture. Still, it seems a shame to lose the analogy of transformation afforded by the evolution from clay to ceramic.

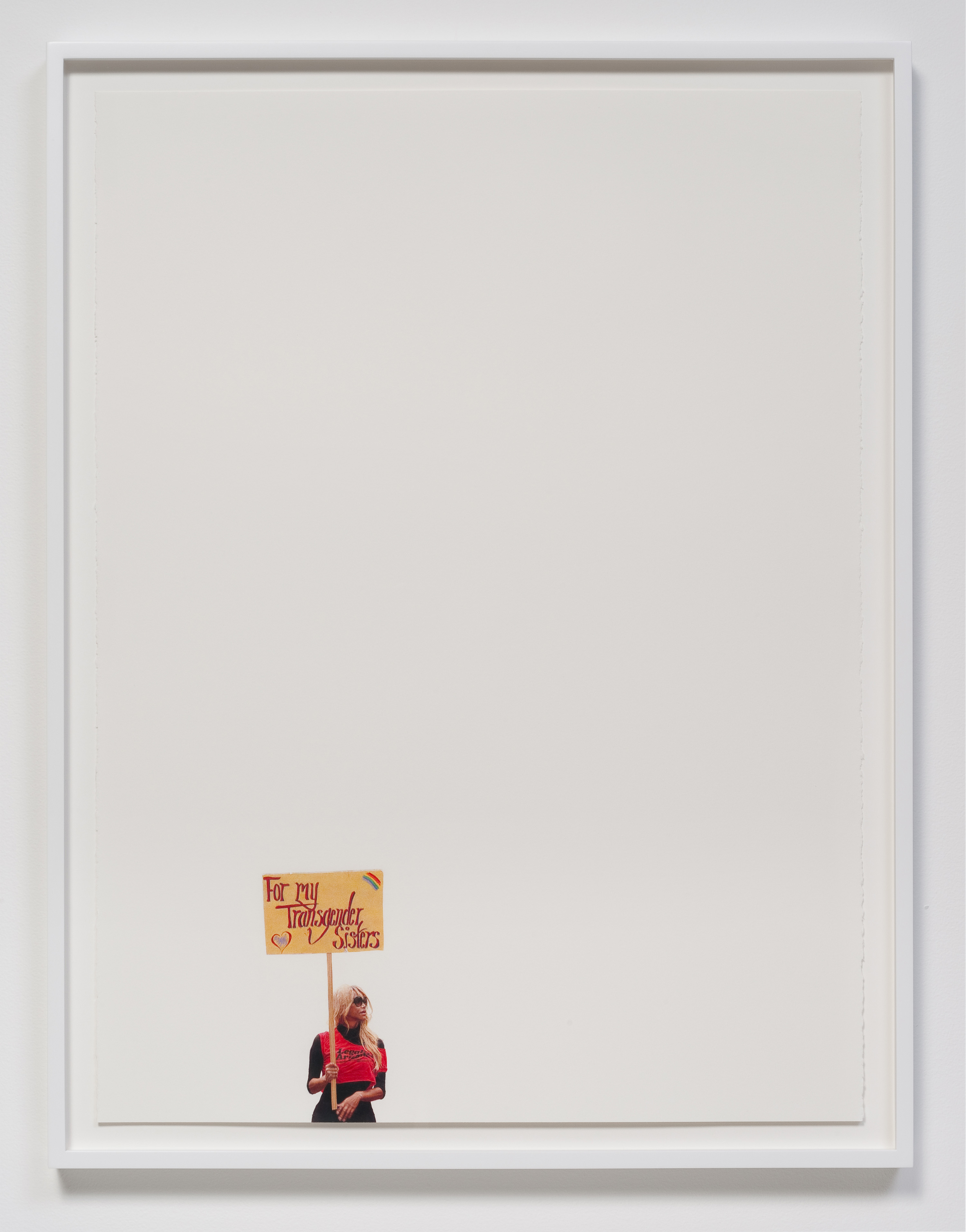

Looking on to this scene is a drawing by Andrea Bowers, For My Transgender Sisters (May Day March, Los Angeles, 2012), showing a solitary figure marching with a protest sign (fig. 2). No other figures are present, but the sole individual speaks for many. A collective solidarity is felt rather than seen.

Queer California is also a sexy exhibition. This is an aspect of queer life that too often is overlooked or ignored in public. Barbara Hammer’s short experimental film Dyketactics (1974) is erotic, tender, and awash in the warmth of desire. Torreya Cummings contributes to the more explicit aspects of the exhibition as well with her series of photographs titled Hard Rocks (2014). She restaged some images from a 1970s gay porn magazine that showed some studs hanging around dressed as cowboys. Cummings reimagined the images with what feels like a group of her friends. Although everyone is unmistakably in costume, faux mustaches and all, the scenes feel quite earnest. In the remaking of a fantasy, somehow the real is what surfaces.

Graceful moves that weave documentary images to creative narrative distinguish Tina Takemoto’s striking video Looking for Jiro (fig. 3). Based in archival research from the GLBT Historical Society, Takemoto found the photographs and personal effects of Jiro Onuma (1904–1990) who immigrated to the United States from Japan in the 1920s and was imprisoned by the American government in an internment camp during World War II. Very little information exists about queer life within internment camps, and so Takemoto set out to imagine Jiro’s persona through a drag king performance video set to a mash-up of songs by Madonna and ABBA. According to the exhibition wall label, Takemoto says she aimed “to imagine how Jiro Onuma survived the isolation, boredom and heteronormativity of the camps as a dandy gay bachelor who is forced to work in the prison mess hall while dreaming of muscular men from his male physique magazines.” Through speculation, Takemoto explores the hidden dimensions of same-sex intimacy as she dances with a broom, makes two loaves of braided bread, then greases up her arms and penetrates the bread so that she can wear them as prosthetic biceps. It is charmingly humorous while also possessing a grief and longing for a past that can never fully be recovered.

A historical exhibition might not be complete without a timeline, and Queer California does not disappoint (fig. 4). Including this didactic helps skirt an assumption that everyone will come to the exhibition with the same cultural knowledge. The timeline, however, complicates the core concept of the show, which is to refrain from a solidified and agreed-upon narrative of a singular queer history. The exhibition deftly avoids presenting the works in chronological order, but the inclusion of a timeline touches on sensitivities to what, even in this inclusive exhibition, remains left out and untold. The struggle to be seen continues, yet Queer California reminds us that there are many ways to achieve many open-ended futures.

Cite this article: Leila Grothe, review of Queer California: Untold Stories, Oakland Museum of California, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2252.

PDF: Grothe, review of Queer California

About the Author(s): Leila Grothe is Associate Curator at the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, California College of the Arts