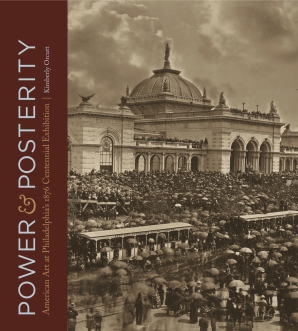

Power and Posterity: American Art at Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibition

Kimberly Orcutt

University Park: Penn State University Press, 2017; 296 pp.; 43 color illus.; 41 b/w illus.; Hardcover $89.95; (ISBN: 9780271078366)

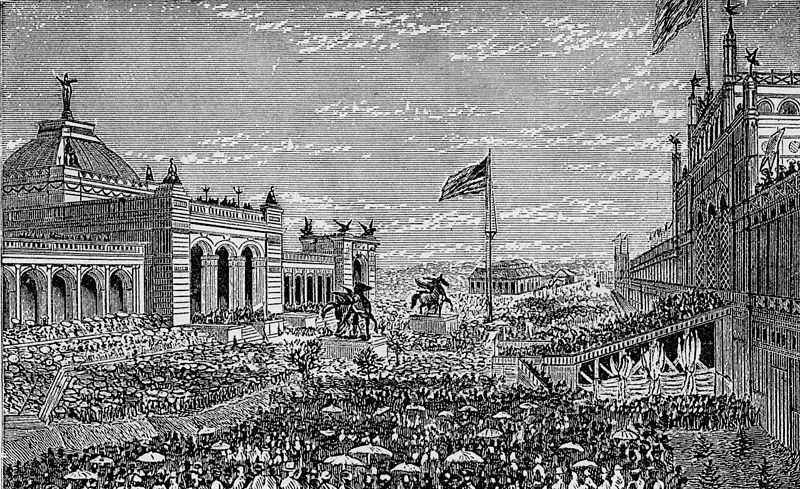

Kimberly Orcutt’s insightful account of the organization and reception of the fine arts display at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia begins quite fittingly with the event’s opening ceremonies on May 10, 1876 (fig. 1). An unexpectedly large crowd gathered in Fairmount Park that day to witness the start of what would be a milestone in American cultural history, as well as one of the most heavily attended and thoroughly documented public experiences of the nineteenth century. The grand scale of pageantry reflected the freighted ambitions of this first major world’s fair to take place on US soil (fig. 2). Hours of patriotic speeches were followed by a hundred-gun salute and a one thousand-person choir singing Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus.” Inevitably, such pomp resulted in defeated expectations. Orcutt notes that even from the first, direct experience of the fair greatly diverged from the organizers’ desired narratives. One newspaper reporter wryly observed that a solemn procession of dignitaries, described in an official program to include President Ulysses S. Grant and Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, would surely have made an imposing spectacle—if only it had been possible to spot it through the hordes of gathered spectators. In their eagerness to bear witness to history, American viewers overwhelmed the very events in which they hoped to participate, so that even from its beginning, the 1876 Centennial Exhibition proved difficult to see clearly.

Orcutt surmounts this obstacle by culling through voluminous period guidebooks, newspaper accounts, photographs, poems, and satire, as well as official records, to assemble an in-depth study of the fine art featured in this celebration and the ways it informed and reflected period debates surrounding national identity and America’s relationship to its own history. The Centennial ostensibly commemorated the hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, although, as Orcutt points out, its underlying stakes were considerably higher. Just a decade after the close of the Civil War, this devastating conflict remained fresh in national memory. Many perceived the Centennial as an opportunity to heal the cultural rift between North and South—not by reckoning directly with recent events, but by mining the nobler origins of the country to fashion a new model for American identity. In this way, the exhibition marked a self-conscious pivot point in US history, “a break between past and future,” as Orcutt describes it, when nineteenth-century Americans sought reassurance “that treasured national values remained intact and that a reunified nation could move confidently into a larger, more complicated modern world” (10).

Art and visual experience played a crucial role in this undertaking, and Orcutt focuses on the ways that American art, artists, and collectors shaped this national dialogue to make a valuable contribution to the history of art in the United States during the late nineteenth century. Like the country as a whole, the American art world was at a crossroads in 1876, as patrons, galleries, critics, and a viewing public vied to define a national school against the factional skirmishes of a nativist old guard and a younger generation of cosmopolitan expatriates. Orcutt argues that an event such as the Centennial, which was packaged for posterity and immediate mass consumption even as it occurred, presents an opportunity for modern scholars to observe past actors caught in a moment of cultural reflection, attempting to write their own history—or more precisely, their own art history—in real time.

The book is divided into three main parts that examine the organization of the fine art exhibition and its legacy as related to American artists, museums, and collecting. Each section is composed of two chapters that focus on the role of a particular constituency and how it exercised its cultural authority through the fair. Part one explores the role of artists as exhibitors and organizers in shaping the fair’s narrative about American art of the past, present, and future. In the first chapter, which makes a particularly strong addition to scholarship on the subject, Orcutt describes the long and contentious process of organizing the selection and arrangement of works of American painting and sculpture on display in Memorial Hall (fig. 3).1 Planning for the fine art pavilion began late, which added pressure to an already high-stakes process. In an unusual move for period fairs, artists rather than collectors or government officials were given complete responsibility for assembling the exhibition and determining how it would be arranged.

Orcutt’s scholarly perspective as a curator proves methodologically valuable here as she evaluates how the selection and arrangement of individual works shaped the overall message of the fine arts exhibition. Drawing upon period letters and journals, particularly the correspondence of the embattled Bureau of Art chief John Sartain, the author presents a cohesive narrative of how the final form of the exhibition was shaped by practicalities of shipping, construction, and scheduling as much as any overarching aesthetic vision. Regional rivalries between art world leaders from Philadelphia, Boston, and New York played a significant role as well. The most notorious outcome of these internal battles was the rejection of Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic (1875; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Art Museum) from display in Memorial Hall, but Orcutt uses the lesser-known but related exclusion of the Orientalist tableau Almeh: A Dream of Alhambra (date and location unknown) by another Philadelphia artist, H. Humphrey Moore, to illuminate how civic pride intersected with larger debates over the direction and ideal character of American art. The second chapter evaluates how exhibition organizers accomplished the curatorial task of linking past and present so that the American school of 1876 appeared to be the logical culmination of the previous century, with displays divided between historical paintings, foreign-made artworks owned by local collectors, and recent work by living artists. The latter category comprised the largest and most frequently discussed of these sections, although Orcutt persuasively establishes the interconnected significance of all three by using gallery maps and photographs to reconstruct how the halls were hung and analyzing the underlying ideology that guided the organizers’ approach.

Part two of the book examines how the fine art exhibition was received by critics and members of the American public. These categories bleed together slightly due to the inherent difficulty of recovering general opinion through published sources; nonetheless, the author conjures a vivid sense of visitor experience in Memorial Hall by drawing upon newspapers, guidebooks, and firsthand accounts to reconstruct how varying audiences perceived the works of art on display. Chapter three focuses on public reaction to what Orcutt describes as the “nation’s first blockbuster exhibition” (85). Preceding the founding of most major American art museums, the Centennial Exhibition provided uninitiated viewers with their crucial first lesson in art appreciation. Orcutt mines period publications for cartoons, photographs, and gallery maps that creatively recapture the experience of roaming from gallery to gallery during the unusually hot summer of 1876. Visitors complained of stifling temperatures, awkward traffic patterns, and rooms too crowded with art and people to allow for satisfactory viewing. Navigating the exhibition challenged viewers emotionally as well. Though there was an official ban on artwork depicting Civil War subjects, Peter F. Rothermel’s massive painting The Battle of Gettysburg—Pickett’s Charge (1870; The State Museum of Pennsylvania) was slipped past the Bureau of Art’s main committee by prominent Philadelphians. In the midst of a national event that was otherwise devoted to selective memory, this painting’s graphic depiction of the carnage and confusion of battle ignited a firestorm of condemnation. Yet despite this controversy, or perhaps because of it, Orcutt argues that viewing The Battle of Gettysburg provided audiences with the most meaningful art encounter of the exhibition, since it “was not just an exercise in museum etiquette but an emotional and intellectual experience that raised questions and prompted discussions” (101). Whether Centennial visitors appreciated the painting or hated it, Rothermel’s work forced them into confrontation with America’s recent history and demanded they take a position.

For all those who visited the fine art exhibition in person, millions more experienced it secondhand through the critical writing of the period. Orcutt’s fourth chapter examines responses of art writers to the aesthetic vision of American art’s present and future. Corresponding with the beginning of the professionalization of the field, these critical writings opened up a national dialogue on the state of American art that held an influential position in shaping the long-term legacy of the Centennial. Like the artists who organized the show, period art writers were divided over the question of the proper relationship of American art to that of Europe, and the close proximity of foreign and American artwork in Fairmount Park raised sensitive new questions about nascent cultural identity. Orcutt describes how the work of Hudson River School artists, which outnumbered other types of painting in the galleries, became a particular focus for critical ire and praise. Some writers described the wealth of landscapes as an artistic triumph for the country, while others voiced growing disillusionment with “all the wearisome succession of map-like prospects of cultivated country” (123). Ultimately, Orcutt argues, the success of the exhibition was in making public a debate over the character of American art that had been circulating quietly among specialists for years. Art writers created a body of publications that spoke to aspiration as well as opinion and formed new narrative histories of American art along with a fresh sense of the power critics had to determine its history.

The third and final section of the book examines how market forces shaped the selection of European artwork displayed at the Centennial both in the Fairmount Park international galleries and the works loaned by American collectors. The fifth chapter focuses on the former, examining how the artwork submitted by European delegations provoked anxiety regarding international perceptions of American taste. The Centennial organizers initially hoped that foreign art contributions would align conceptually with their planned display of American art by presenting the best available European contemporary art for the edification of gallery visitors. The contributions from the French and Italian delegations proved especially frustrating to those who held this expectation. Instead of museum-quality work, these submissions more closely resembled a gallery show of sculpture and painting for purchase, including decorative work by stonecutters and middling-quality portraits of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin whose selection appeared motivated to generate sales to undiscriminating Americans. In addition to exposing the awkward divide between commercialism and commemoration that characterized most nineteenth-century world’s fairs, the low quality of work in the French and Italian galleries struck a nerve by implying that American viewers and collectors might not be able to tell the difference.

Chapter six looks beyond Philadelphia to the New York Centennial Loan Exhibition, a display of art drawn from the private galleries of American collectors that ran almost concurrently with the exhibition in Fairmount Park (167). This rich assembly of European academic and Old Master paintings was conceived as a showcase for American wealth and taste, and it eclipsed the offerings in the international galleries in Philadelphia in terms of quantity and quality. Orcutt writes that the New York exhibition represented a kind of “riposte” to the insulting submissions of the European delegations and the perceived liberties taken by Sartain and other Philadelphians in selecting work for the American galleries. The chapter reads as a slight departure from the more nuanced delineation of regional “Art Worlds” that distinguish the earlier chapters, since New York collectors appear to gain the last word in period debates over aesthetics and spectatorship by mounting an exhibition that reached a considerably smaller audience that the Centennial Exhibition. Nonetheless, Orcutt persuasively connects the successes, failures, and sky-high ambitions that animated the American art world with the priorities that sparked the American museum movement in the years to follow.

Whereas previous studies locate the Centennial Exhibition within the consumer emporia of world’s fairs or examine the event in its totality, Orcutt’s focused exhibition history is a valuable tool for research and teaching, especially her chapters on the organization and public experience of the fine art galleries. One small point of contention is the relatively limited scope of the study in terms of visual media. Orcutt’s explanation at the outset is that her chosen focus on painting and sculpture follows definitions of fine art put forward by the Centennial Exhibition organizers, although one can only imagine how probing the fault lines in period media hierarchy might have supported her exploration of the relationship between art and power during this period—especially as photography and prints continually creep into her study as mediations of the other artwork under discussion. However, this does not diminish Orcutt’s impressive feat of scholarship so much as it suggests productive directions for future studies. Like the festivities of its opening ceremonies, the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition was a historical event so sprawling in its execution and cultural impact that its legacy has been hard to perceive. Demonstrating careful research and astute observation of the powerful role curatorial acts can play in the shaping of history, Orcutt’s insightful scholarship offers a fresh perspective on this pivotal moment in American art history and its continuing reverberations in the art world today.

Cite this article: Erin Pauwels, review of Power and Posterity: American Art at Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibition, by Kimberly Orcutt, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1690.

PDF: Pauwels, review of Power and Posterity

Notes

- Previous studies of the Centennial Exhibition include: Bruno Giberti, Designing the Centennial: A History of the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002); Susanna W. Gold, The Unfinished Exhibition: Visualizing Myth, Memory, and the Shadow of the Civil War in Centennial America. (New York: Routledge, 2017); Robert Rydell, All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Exhibitions, 1876–1916 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984); and Robert Rydell, John E. Findling, and Kimberly D. Pelle, Fair America: World’s Fairs in the United States (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000). ↵

About the Author(s): Erin Pauwels is Assistant Professor of Art History at Temple University