Mikva Dreams: Judaism, Feminism, and Maintenance in the Art of Mierle Laderman Ukeles

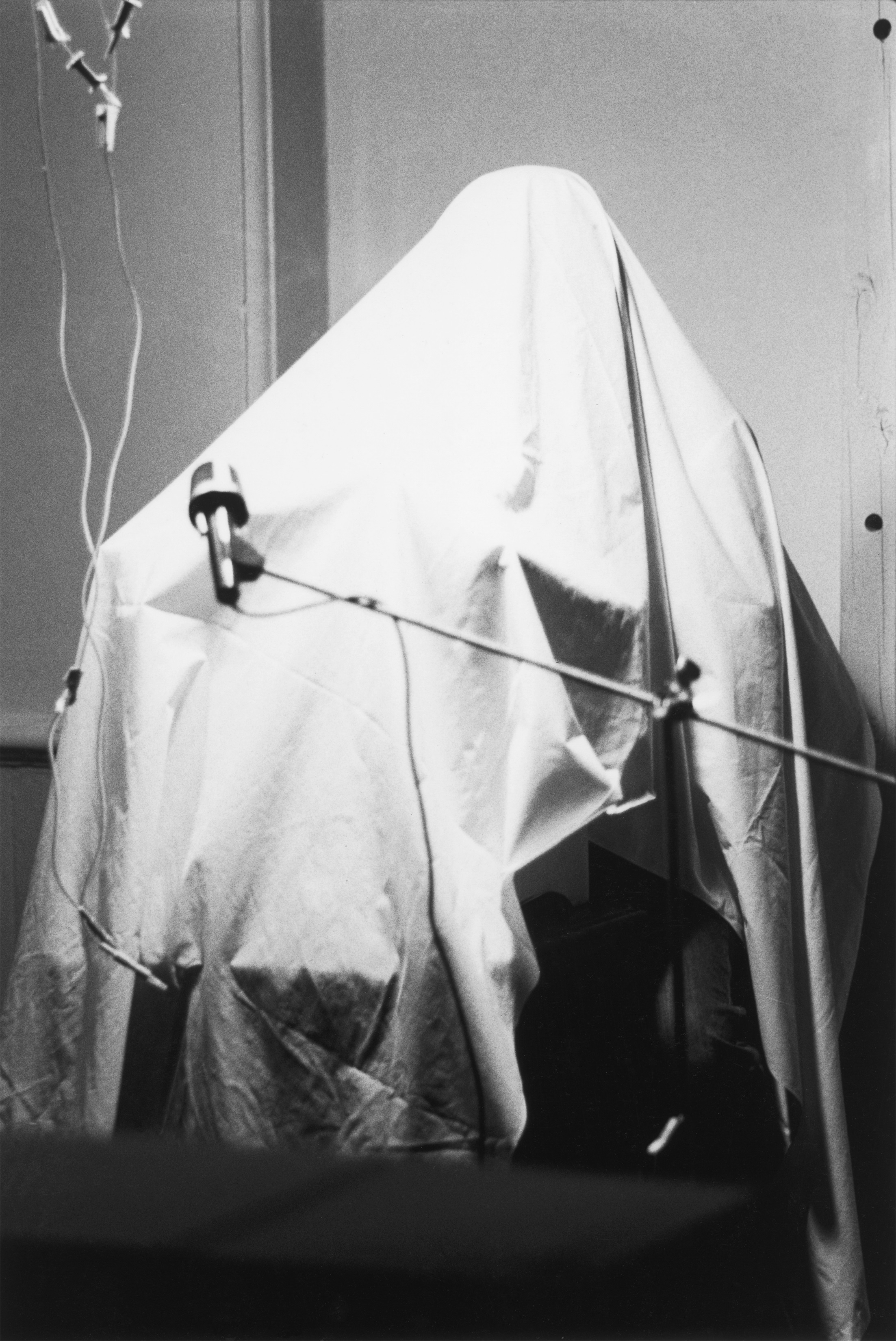

When Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b. 1939) performed Mikva Dreams at New York’s Franklin Furnace Gallery in 1977, it was the first time the immersion of a Jewish woman in the mikvah had been presented to an audience for American art. Seated in the gallery, Ukeles read aloud from a text she had written, while covering herself with a white sheet, “to preserve,” in her words, “an aura of sacred mystery and privacy” (fig. 1).1 In her performance, she described the immersion in the mikvah as an act of rebirth and a return to the Garden of Eden, extolling it as a ritual that connects a woman with her inner being.

The laws of immersion in the mikvah were not foreign to the Orthodox artist. In Orthodox Judaism, the mikvah serves to achieve ritual purity after the nidda (menstrual flow), during which a Jewish couple is forbidden from having physical contact or performing any act that might lead to physical intimacy. After the cessation of her menstrual period, the Orthodox Jewish woman immerses herself in a mikvah before resuming sexual relations with her husband. When a woman immerses in the mikvah, all of her body, including her hair, must be submerged in the water; anything that adheres to the body or hair and prevents direct contact with the water invalidates the immersion. The act of ritual immersion in the mikvah also serves as part of the process of conversion, which joins a person (male or female) to the Jewish people. Additionally, it is customary for men in some Jewish communities to immerse in the mikvah before the morning prayer, and many Jewish men immerse on the eve of the High Holidays.

Any natural gathering of running water constitutes a natural mikvah: lake, river, or sea. In urban areas, the mikvah is built using an approximation of natural water, that is, rainwater collected through the force of gravity via a duct and mixed with tap water. The mikvah is constructed like a small bathing pool. The “Bor” (“Otzar”) is the part of the mikvah in which the rainwater is stored; it is connected by a pipe (known as the “kissing pipe”) to the ritual bath, where the rainwater is mixed with ordinary tap water.

Mikva Dreams, which referred to the laws of nidda and to the immersion experience in the mikvah, was the first work in a series created by Ukeles in the 1970s and 1980s that dealt with the mikvah from a religious and feminist perspective. While the study of feminist thought and activism is well developed, the study of religious feminist art is not. Scholars determined to diversify our understanding of American art have yet to include religious feminist art, and more particularly Jewish feminist art, in the discussion. Although Ukeles is known for her public and environmental “maintenance art” from the 1970s and 1980s, her focus on religion during this same period is not well known. By focusing on Mikva Dreams and her other mikvah projects, this article contextualizes and makes better visible Ukeles’s contribution to contemporary American art and its feminist discourses.

Critics and art historians have marginalized Ukeles’s art about religion. Whereas her secular maintenance art has been exhibited in major art institutions and become part of the American art canon, her religious art, created during the same period, has been the subject of little critical study. The tendency to exclude art that concerns religion, which has characterized American scholarship and art criticism, may partly account for this omission. Samantha Baskind has investigated the reception of Jewish artists in the United States and found that work that did not explicitly deal with Jewish themes became part of the canon of American art, whereas work dealing with Jewish identity and sensibility did not.2 Baskind’s findings provide support for Sally Promey’s claim that until the 1990s, art historians embraced the modern secularization thesis—the idea that traditional religions are in decline in the industrialized world—and therefore failed to include art with religious content in the canon.3 Furthermore, Promey showed that until the 1990s, art about religion was discussed in scholarly studies only when it could be classified in secular terms.4 Rosalind Krauss noted the emergence of an “absolute rift” between art and religion following the desacralization of art in the nineteenth century,5 and visual culture scholar Kajri Jain expressed a similar idea, stating: “I think that contemporary art just doesn’t ‘do’ religion.”6 In 2004, art scholar James Elkins published On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art, in which he too pointed to the repression of art linked to religion in contemporary art discourse.7

Critics and curators who study American Jewish art have likewise avoided art about religion. In the 1970s and 1980s, Jewish themes were considered kitschy and consequently excluded from the history of Jewish American art. Norman Kleeblatt, who curated Too Jewish? Challenging Traditional Identities in 1996, developed that exhibition upon realizing that the biblical imagery produced by Archie Rand (b. 1949) was “too Jewish” to exhibit at the Jewish Museum in New York.8 He wanted to analyze this paradox, as well as to understand his own discomfort as an assimilated Jew before these works.9 Even today, themes related to the Jewish religion do not form the primary concern at the Jewish Museum in New York, one of the most important Jewish art institutions in the United States.10 Therefore, the secularization of American art, scholarship, and criticism helps to explain the differing receptions accorded to Ukeles’s maintenance art and her work about religion.

The Jewish and religious content in Ukeles’s work has only recently begun to receive greater visibility. For example, New York Times art critic Holland Cotter, writing in 2016 about the artist’s retrospective exhibition at the Queens Museum in New York, explicitly remarked on the Jewish context of her work.11 Similarly, the art critic and curator Lucy Lippard, in her essay in the book that accompanied this same exhibition, wrote that “for all her avant-garde flair and eventual art world recognition, she has maintained her traditional Jewish faith.”12 The book’s main essay, written by the exhibition curator Patricia Phillips, includes a survey of Ukeles’s Jewish-themed art and even points to the Jewish and religious aspects of her maintenance art, which had not previously been discussed.13 This article builds on these observations by bringing Ukeles’ Mikva Dreams and her other mikvah projects explicitly into the scholarly conversation, arguing that the artist understood them as an empowering feminist exploration of women’s bodies, spirituality, and roles within Judaism and the family. In so doing, she demonstrated that religion, feminism, and art are not as antithetical as some had claimed.

Ukeles’s Mikvah Works in the 1970s and 1980s

The treatment of ritual immersion and the mikvah, which I argue is integrally connected to the maintenance work for which she is well known, was central to Ukeles’s artistic practice in the 1970s and 1980s. The performance of Mikva Dreams began with a declaration by the artist: “Sisters! In this new time for all of us, I take this time to tell you of these private things.”14 Ukeles then read a detailed description of the technical aspects of constructing a mikvah. She followed this methodical description by reading from a script written in the third person about her own personal experience of the ritual immersion, from the preparations, through the act itself, to the feeling of joy it gave her: “She goes in, naked, all dead edges removed. . . . The Mikva is for her intrinsic self. Her self-self. . . . The blood stopped flowing a week ago. She is the moon.”15 The artist also presented the practical aspects of the immersion as a ritual with erotic characteristics:

In all the gentleness of continuing love, she goes to the Mikva. The Mikva water hit above her breasts when she is standing up. The waters have pressure in them. She pushes into it as she comes down the steps. When she leaves, it seems as if the waters softly bulge her out, back to the world. No, she doesn’t want to tell you about it. It is a secret between her and herself. . . . The water is warm, body temperature . . . a square womb of living waters.16

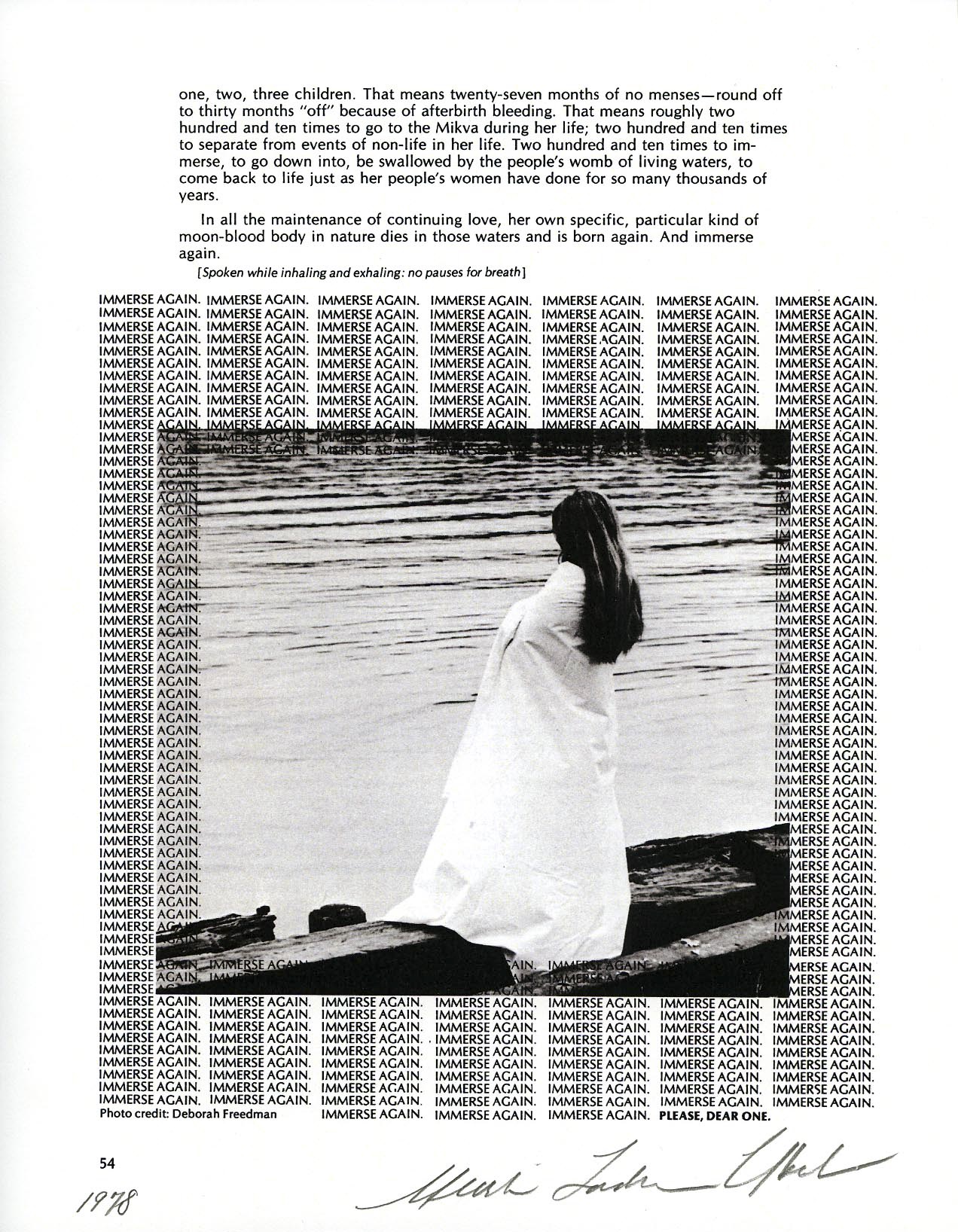

The performance concluded with a meditation, during which the artist repeated the words “immerse again” two hundred and ten times, the number of times which, according to her calculation, she might immerse in the mikvah during her reproductive years. The performance, which included no other sculptural objects or elements, portrayed the mikvah and immersion in it as an elevated ritual that connects feminist consciousness with Jewish ritual.17 Ukeles presented immersion as a personal and intimate act, though at the same time her performance included a public and political call to be reborn as both Jewish and feminist women.

In a second version of the performance, produced for a 1978 issue of Heresies magazine dedicated to the goddess in history and contemporary life, Ukeles again draped herself in a white sheet.18 This time she performed the work alone, with no audience, standing on the banks of the Hudson River in New York.19 Ukeles transformed the performative and vocal properties of the work into three pages of text and a static image for the magazine (figs. 2 and 3). The photograph, depicting the artist from behind, draped in a sheet and standing before the river, was surrounded by 210 repetitions of the words “Immerse Again.” As at Franklin Furnace, she called on her “sisters” to be reborn as both Jewish and feminist women, concluding her recitation in Heresies with the words: “Please Dear One.”

Despite the uniqueness of Mikva Dreams, this work did not have a broad impact, and there were no reviews written of it at the time. It was only later, in 1992, that the text of Mikva Dreams and its printed representation were included in the feminist Jewish anthology Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality: A Sourcebook, edited by Ellen Umansky and Dianne Ashton.20 In the book, the editors characterized the work as a symbol of female purification and noted the way it channels the theme of immersion into an extremely personal route, in their words, “deriving its form and actuality from the artist’s profound Jewish consciousness.”21

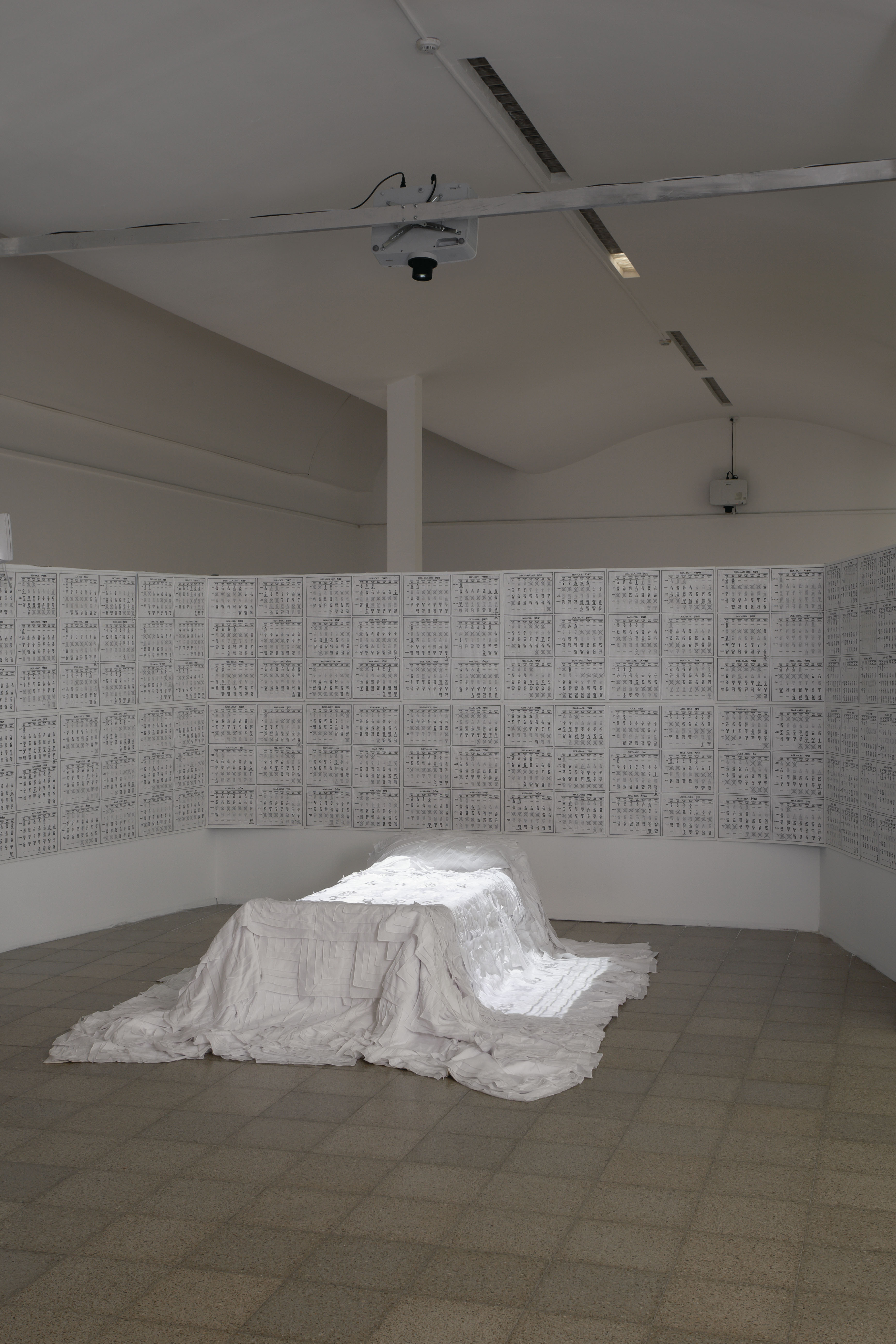

In 1986, Ukeles exhibited a third mikvah work, this time in the form of an installation that she constructed at the Jewish Museum as part of a group exhibition, “Jewish Themes/Contemporary American Artists II,” curated by Susan Tumarkin Goodman. This installation, entitled Mikvah: The Place of Kissing Waters and Double Doors of Transformation, Ready? Ready! consisted of a mikvah built within the walls of the museum (fig. 4). This was the artist’s interpretation of the traditional mikvah structure and the experience of transition that immersion is meant to generate. It was not used for actual performance, and although no water was used in the work, the artist otherwise structured the bath in accordance with the dictates of Jewish law regarding materials and measurement.

The upper floor of the installation served as the entrance to Ukeles’s mikvah, a sort of preparatory room for immersion. It contained a bathtub cut in half and a wall of folded towels and soap shaped into blocks (figs. 5 and 6). The artist marked the connection between the cycle of the female body and the lunar cycle by hanging on the wall four circular hand-cast lamps simulating the moon as it appears at different stages of the month. Echoing her claim that the essence of Jewish thought lies in transformation and cyclical rebirth, at the entrance of the mikvah, before the staircase, she placed two doors, one in front of the other, one as an entrance and the other as an exit (fig. 7). For the artist, these two doors symbolized the two circumstances necessary for creating the transformation: the entrance door represented the woman’s willingness for rebirth, and the exit door, society’s readiness to accept the rebirth she has undergone.

The staircase that would ordinarily provide access from the upper to lower sections of the mikvah was replaced in Ukeles’s installation by an unusual set of transparent triangular stairs in which each step faced a different direction, a structure designed to suggest the idea of immersion as a transition from one state of consciousness to another (fig. 4). Ukeles explained that with every step a woman takes down the stairs, she must consciously choose to move from one condition to the next.22

Beneath the entrance floor and next to the immersing area was the “Bor,” a gray, well-shaped structure in which the rainwater is stored (fig. 8). From deep inside emanated a sound work composed of the natural sound of falling rain. Whereas the Bor in a traditional mikvah is covered and unseen, like plumbing, in Ukeles’s mikvah, it was in plain sight. As in her maintenance art, the artist exposed mechanisms that usually remain invisible. The Bor was made of thin concrete over a steel armature in a configuration resembling the organic shape of a vagina. It also recalled ancient mikvahs carved out of rock, which have been uncovered in archaeological excavations. On the left side was a copper tap to suggest the bringing of city water into the mikvah (fig. 9). On the right was a blue PVC pipe that came down from the roof of the museum, ran inside the building and across its lobby, and suggested the pipe that collects rainwater (“Heaven’s waters”) for the mikvah (figs. 10 and 11). Ukeles stressed in her artist’s statement that as an environmental artist she was interested in technical solutions such as gravity-fed systems for collecting, grounding, and storing “holy” natural water, adding that she was fascinated by “the Rabbis’ ancient invention of an urban structure where a proper amount of this natural water can ‘kiss’ more plentiful regular city water into efficacious holiness!”23

Figs. 5–12. Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Mikva: The Place of Kissing Waters (details), 1986.

© Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York, NY

The walls of the immersing area of the mikvah were covered, as is customary, with tiles. Here the artist hung layers of stiffened white sheets similar to the sheet in which she covered herself in her Mikva Dreams performances a decade earlier (fig. 12). Ukeles described the sheets as “a poetic progressive series of a person who would have entered the mikvah covered with a sheet that gradually opens it out and then tosses it away to become re-born.”24 The layers of sheets were coated with transparent pearlescent paint, which created a glowing appearance, and in some parts of the sheets, the paint concentration produced a yellow viscous substance resembling body secretion. Some of the sheets were wrapped around themselves to suggest the forms of a fallopian tube, umbilical cord, or fetus, connecting immersion in the mikvah to birth, as in her previous performances. Ukeles wrote in her artist’s statement for the catalogue that the mikvah is “the woman’s ancient place . . . a site devoted to honoring each Jewish woman’s sacred moon-body cycles.”25 She also referred to the similarity of the mikvah to “Stonehenge and sacred earth mounds, that mark, month by month, the cumulative story of each woman’s life measures of possible fecundity.”26 As in her earlier performances, immersion in this installation was presented as an act of recreation connecting a renewed feminist consciousness with the rituals of Orthodox Judaism.

The installation at the Jewish Museum was not used for performance, but the artist did organize a performance in the auditorium of the museum that was attended by several hundred people during this same exhibition. This performance focused on the transformative act of ritual immersion in the mikvah as part of the process of conversion, which is used to join a person to the Jewish people27 The piece was inspired by the mid-1980s controversy over the Jewishness of the Ethiopian Jews, many of whom had escaped great hardship to immigrate to Israel with the help of the state. The Israeli Rabbinate had declared that their Jewishness was questionable, and they therefore had to convert by immersing in a mikvah. Ukeles was outraged by this ruling, and she created this performance in response. She also commented on the political role that the mikvah had come to play, arguing that “[as a] central locus of conversion, mikva has become the hollow place where all the empty waves of disunity and non-acceptance among Orthodox, Conservative and Reform authorities reverberate around who and how one becomes a Jew.”28 She proposed, instead, that “we should each and all go to the mikva and immerse again, and therefore convert all of us to get started over. . . . Then no one would be more Jewish than any other!”

The conversion performance was held in the darkened museum auditorium, with spotlights directed at different elements of the set. This created an intensely dramatic scene. Forty people invited by the artist, representing different ages and parts of the American Jewish community, held together a big sheet of clear blue plexiglass symbolizing a river. They raised the river over their heads as if they were all at once immersing in the water (fig. 13). Meanwhile, another group of volunteers from the audience, serving as witnesses to the conversion, stood under a gate created onstage by the artist. The participants spoke about their Jewish identity and the possibility of Jewish unity. As Ukeles recounted, “Some believed in Jewish unity, and others did not, it was up to them to share their thoughts.”29 The performance was accompanied by a video, shown on a very large screen at the front of the auditorium, featuring Ukeles’s husband immersing in a mikvah. This performance, as in her Franklin Furnace and her Hudson River performances, also dealt with the process of transformation made possible by immersion in the mikvah.

The “Jewish Themes/Contemporary American Artists II” exhibition did not have a significant impact on the art world, although it was reviewed and several critics discussed Ukeles’s work. Michael Brenson described the exhibition in the New York Times as significant in the way that it announced that old themes, new art, and fresh approaches to media and materials can enhance each other in compelling and dramatic ways. He called Ukeles’s Mikva Dreams “a complex installation dealing with ritual and purification.”30 Lynne Rosenthal wrote in the New York City Tribune that “Ukeles has constructed many site-specific projects, but none, perhaps as mysterious and conducive to bodily-spiritual cleansing and transformation as this.”31 Nevertheless, Ukeles’s commitment to representing an enduring ritual of Jewish culture, and her connection of this history to contemporary practice, was also criticized as an engagement in transgression and taboo.32 In a 2006 interview with gallerist and curator Marisa Newman, Ukeles spoke in hindsight about her disappointment at the response to her work from this period.33 Despite the specifically religious context of her installation and performance, and despite her desire to be active as an Orthodox Jew, Ukeles had her work completely ignored by the Orthodox Jewish community.

Mikva Dreams and the Feminist Spirituality Movement

With her mikvah work, Ukeles was participating in the spirituality movement that was a significant part of American feminist art in the 1970s.34 Many artists, among them Nancy Spero (1926–2009), Rachel Rosenthal (1926–2015), Audrey Flack (b. 1931), Mary Beth Edelson (b. 1933), Judy Chicago (b. 1939), Betsy Damon (b. 1940), and Donna Henes (b. 1945), participated in the Great Goddess movement, turning to the ancient goddesses as a source of inspiration and adopting matriarchal ideas from the past to enrich the feminist experience and discourse of the present.35 Some, such as Adelson, Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019), Damon, and Ana Mendieta (1948–1985), like Ukeles, were creating feminist performances.36 Although performance art provided a critical means for connecting art to daily life, feminist performance artists also gave ceremony a central place in their work by re-mystifying it, returning to art some sense of the sacred that had been lost in modern times.37

Ukeles did not explicitly partake in the Great Goddess movement, which was centered in Southern California and not New York,38 but her Jewish-themed works did comment on contemporary feminist experience by exalting women’s religious rituals. Her Mikva Dreams performances were similar to feminist spiritual meetings held in the 1970s, especially those in which enactment was intended to reinvigorate the Great Goddess religions. During these gatherings, a self-described priestess, or witch, held a public ceremony that combined discussion of “femininity” with a critique of patriarchal religions.39 Ukeles likewise used her performances to praise the act of ritual immersion, and her language is comparable to that used in the Great Goddess discourse:

Like most goddess traditions, Matronit-Shechina, the Jew’s female divinity, has been pictured from ancient times as magically combining all these aspects: eternal renewed virgin, and eternal passionate lover, and eternal creating mother. Mikva is the site-intersection of all these holy energies.40

Therefore, the artist designed Mikva Dreams in the spirit of the Great Goddess. She sought to connect herself and the viewers of her performance to the ceremony of Jewish ritual immersion, which she saw as a source of divine energies handed down by women from generation to generation. And indeed, the 1978 issue of Heresies in which her text and a photograph of her performance were published was devoted entirely to the Great Goddess movement.

Moreover, Ukeles’s turn to the theme of mikvah can be understood as part of the move to develop the iconography of the spiritual feminist movement, which was inspired by feminist body art to involve “the artist’s body in either production or performance.”41 Many American feminist artists working in the 1960s and 1970s presented the female body as a symbol of women’s liberation and as opposed to the repressive patriarchal order.42 Artists Joan Semmel (b. 1932), Eleanor Antin (b. 1935), Chicago, Hannah Wilke (1940–1993), Lynda Benglis (b. 1941), Tee Corinne (1943–2006), Faith Wilding (b. 1943), Suzanne Santoro (b. 1946), and Karen Le Cocq (b. 1949) created work that focused on female sexuality as a vital and multivalent aspect of female experience.43 Feminist performance artists Barbara Turner Smith (b. 1931), Yoko Ono (b. 1933), Schneemann, Marina Abramović (b. 1945), Adrian Piper (b. 1948), and Mendieta likewise used their body to demonstrate the objectification of women and its results, pushing the limits of sexual taboo.44

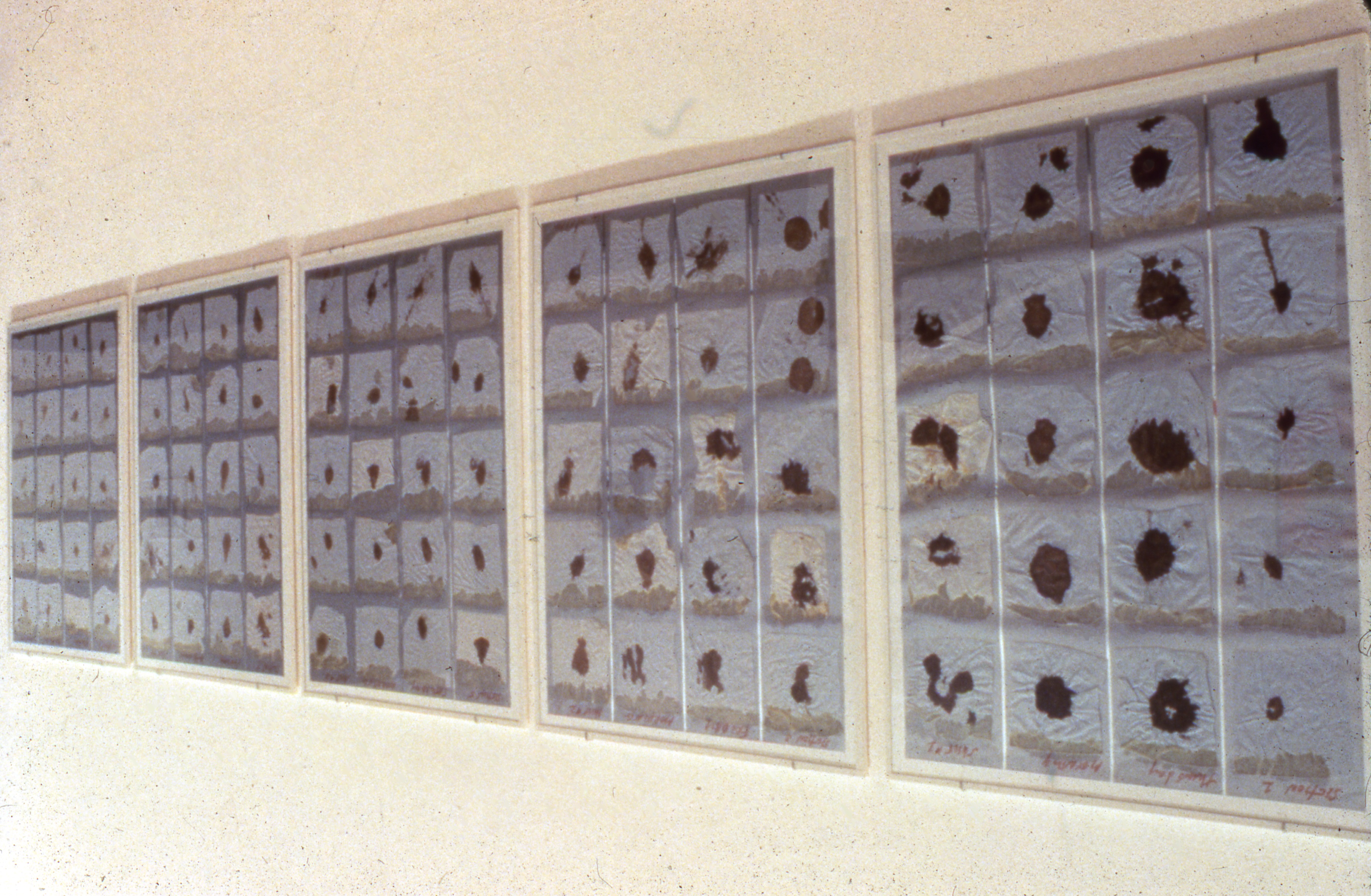

Ukeles, like several other American feminist artists at the time, engaged with the taboo subject of menstruation, and, like them, she worked to reclaim it as a site of power rather than shame.45 Chicago created a photolithograph titled Red Flag, in which she is seen from her waist down, pulling a blood-soaked tampon out of her vagina in 1971.46 In 1972, her installation Menstruation Bathroom at the Los Angeles Womanhouse featured, among other things, a trashcan overflowing with tampons and pads soaked in blood-red paint, evoking, in her words, “everything that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light” (fig. 14).47 Similarly, Wilding confronted the social shame of menstruation in Sacrifice (1971), a tableau in which a wax effigy of the artist, covered with decaying animal intestines, lay before an altar of feminine hygiene products.48 Schneemann, for her part, incorporated her own menstrual blood into her 1972 gridded artwork Blood Work Diary, examining the texture and color of her blood stains (fig. 15). The way in which the material of her body is presented in the work, she explained, indicates a dynamic of autonomous feminine aesthetics, which is not categorized or judged through the dichotomies of impure-pure.49 Similarly, in her Interior Scroll performances from 1975 and 1977, she pulled a menstrual blood-stained scroll out of her vagina and read it in public.50 Schneemann and other feminist artists linked their artistic activity to the Great Goddess, seeing in its forms and images the source of the sacred feminine knowledge connected to birth and transformation.51 These artists’ works were accepted and discussed as significant contributions to feminism,52 and their art was embraced by the spiritual feminist movement. Although Ukeles’s mikvah works were not accepted into the canon of feminist art, they too should be seen in the context of this movement. She explored the cycles of a woman’s body through her treatment of the theme of mikvah and subverted the traditional meaning of the ritual by making it public.

Despite the evident connection between Mikva Dreams and the feminist Goddess movement, Ukeles’s work is also distinct from it. The dominant feminist exchanges in the United States during the 1970s linked Jewish law regarding menstruation with the patriarchal view that menstrual blood is impure, which led feminists to critique the Jewish laws of purity. In an interview by Linda Montano, published in 2000, Ukeles explained that many feminist women in the 1970s objected to the ritual of the mikvah and viewed it as primitive, whereas she saw it as a continuation of the matriarchal religion of the past.53 The artist expressed this position in her performance of Mikva Dreams, when she stated that “misunderstandings have adhered to the concept and power of the Mikva. No. Mikva is not about women as dirty.”54 In contrast to dominant feminist beliefs of the 1970s, Ukeles consistently produced work that aimed to reclaim immersion practices as empowering rituals for women, an approach that was prevalent in American Orthodox Jewish feminism at the time.

Ukeles’s understanding of the ritual of immersion is brought into relief by considering the difference between Christian and Jewish feminist criticism in the United States. Whereas Christian discussions were divided between those who sought to fix the church and those who broke with church institutions and founded a new religion based on feminine spirituality,55 in the various religious branches of Jewish feminism there was rarely a demand to split from traditional institutions, nor was there a call to establish a post-Judaic religion.56 Feminist Jewish theologians criticized Jewish rituals and texts through acts of interpretation and the reclamation of elements from within Jewish tradition which they viewed as feminine. Rather than disengage from it, they chose instead to reinvent it.57 Ukeles likewise connected feminism with the thought of Orthodox Jewish feminists of the time, proposing a reinterpretation of the laws of nidda that freed them from the dichotomy of pure and impure as shaped by the rabbinical tradition.

Public discussion of women’s ritual immersion was taboo in Ashkenazi )Jews of eastern European origin( religious Jewish communities at this time, and Ukeles argued that this veil of secrecy was a patriarchal construction. In her performance of Mikva Dreams, she explained that the menstrual ritual had barely survived “these centuries of cultural hang-ups toward menstruation itself: superstitions which are really fear and loathing of a woman’s body itself, woman’s deep mysterious fertile magic body and her times.”58 She presented her work as an alternative to those who marked menstrual blood as dirty, insisting instead that the Jewish ritual of immersion was not based on a distinction between pure and impure.

In her performance of Mikva Dreams, Ukeles quoted Rachel Adler, a prominent Jewish feminist theologian in the United States. Adler, who presented a feminist critique of Jewish thought and halakah (Jewish law) in the 1970s, held a sympathetic view of ritual bathing and the laws of nidda at this time.59 Jewish Orthodox feminist thinker Blu Greenberg wrote a poem around this same time in which she praised the experience of immersing in the mikvah, especially commending the cooperation between the immersing woman and the mikvah attendant.60 Indeed, Ukeles’s text for Mikva Dreams is reminiscent of Greenberg’s poem in its exaltation of the ritual bath attendant and the practice of purification. In this way, Ukeles’s work aligns with Jewish feminist thought, reclaiming the ritual immersion practice as an empowering rite for Jewish women. Yet, while Ukeles expressed notions that were typical of Orthodox Jewish feminists in the United States, she was still exceptional. Most of the American feminist artists of Jewish origin working in the 1970s did not deal overtly with aspects of Jewish religion in their art.61 By contrast, Ukeles dealt with her heritage and religion directly.

Ukeles’s performance was remarkable in the broader non-Jewish feminist context of the 1970s as well. In the general feminist debate of the 1970s, Judaism was often characterized as a patriarchal religion, an anti-feminist sphere that oppressed women through, among other ways, the religious laws of nidda. But religious Jewish feminists rejected this characterization. Reflecting upon negative attitudes toward Judaism held by feminists in the 1970s, feminist scholar Susan Gubar observed that to be Jewish and a feminist at this time was perceived as an oxymoron.62 More generally, Jews were still regarded as “other” by mainstream American society.63 Ellen Umansky and Joyce Antler, both of whom have noted anti-Semitic undertones in the American feminist talk of the 1970s, argue that it was these anti-Semitic voices that led some Jewish feminist women to turn toward Jewish tradition and to reclaim it.64

In a parallel process, Jewish women working within the Jewish tradition began to introduce feminism into their own communities with the aim of importing the achievements of feminism into their Jewish milieu. According to Edna Kantorovitz, who has described the unique aspects of Ukeles’s Mikva Dreams performance in the context of 1970s feminist discourse: “It was not unusual then to be told that Judaism was a religion of hatred and retribution with a paternalistic God in contrast to the loving and forgiving Christian religion. Jewish women were thought to hate their bodies because of menstruation and the mikva.”65Kantorovitz argues that Ukeles challenged these assumptions and aimed to reveal an unknown side of Jewish belief. Her appreciation for ritual immersion therefore opposed the predominant feminist discourse while also sharing the spirit of religious Jewish feminists of the 1970s.

The artist herself has stressed the gap between her work and the reigning feminist discourse of the time. Speaking later about the inclusion of Mikva Dreams in the journal Heresies in the late 1970s, Ukeles pointed out that the publication of the work in a feminist journal was not at all self-evident at the time: “I was apprehensive about the piece being accepted by the [Heresies] collective, because there was a lot of anger against patriarchy in Judaism and in religion generally. But it was also very well received.”66 Unlike most Jewish feminist artists, whose works did not focus on religion, and like the religious Jewish feminists, who sought to connect religion and feminism, Ukeles dealt with religious Judaism in public while also remaining conscious of the rift between her work and the mainstream feminist debate. By celebrating the mikvah and its laws, she challenged the prominent secular discourse of both the art and feminist communities, offering them a perspective that does not reject religion but instead renews and celebrates it.

Ukeles’s Mikva Works and American Jewish Feminist Art

The nature of the connection that Ukeles forged between Judaism and feminism can be further developed through comparison of her mikvah projects with the works of two other Jewish American artists whose art dealt with immersion:

Ruth Weisberg (b. 1942), who began creating prints on this theme in the 1970s, and Helène Aylon (b. 1931), whose works on immersion date from 2001. Like Ukeles, Weisberg dealt with immersion in the context of birth and rebirth. Unlike Ukeles, Aylon criticized the laws of ritual immersion, albeit in a subtle way.

Weisberg’s Waterbourne from 1973 depicts a naked woman floating in a pool of water, curled up in a fetal pose. Above her, a reflection of light in warm oranges and reds illuminates the scene (fig. 16).67 Matthew Baigell connects such works by Weisberg, who was active in the feminist art movement in Los Angeles, with the art of the first generation of feminist artists who dealt with birth: Chicago, who created images of women giving birth as part of The Birth Project in the early 1980s, and the feminist art collective that worked with Chicago and Miriam Schapiro (1925–2015) to create the performance Birth Trilogy, shown at Womanhouse in 1972.68 Birth Trilogy served as a ritual of rebirth, symbolizing the community of women who attend their own and one another’s births.69 Baigell claims that, like these artists, Weisberg was dealing with birth in order to reestablish women’s connection to themselves and as a metaphor for their own rebirth as feminist women. Yet, unlike the treatment of birth at Womanhouse, Weisberg (like Ukeles) incorporated immersion into her work.70 Moreover, and again like Ukeles, Weisberg distinguished herself from other feminist artists by dealing with Jewish religious subjects. Yet despite Weisberg’s straightforward presentation of a woman bathing, she did not interpret these works in the context of Jewish ritual immersion; they were presented only as an act of rebirth, with an emphasis on their sensuality. Only later, in the early 2000s, did Weisberg discuss these works in the context of the Jewish ritual of immersion.71 In practice, both Ukeles and Weisberg, as well as Chicago and the Womanhouse collective, brought feminist visibility to women’s biological processes (menstruation and birth), and all these projects offered a metaphor for women’s rebirth as feminists. Therefore, while Ukeles connected feminism with Judaism in the 1970s, clearly and openly presenting ritual bathing in a Jewish context, Weisberg left the Jewish context of her immersion works implicit until later in her career.

Aylon’s work, My Bridal Chamber from 2001, is like Ukeles’s mikvah performances and installation in that it deals directly with the laws of ritual immersion (fig. 17). Where Ukeles refrained from direct criticism of Orthodox Judaism, however, Aylon presented a more ambivalent view. Her installation My Bridal Chamber featured a number of works, among them My Marriage Bed and My Clean Days. In My Marriage Bed the artist covered a bed with white bedika cloths and projected on them images from the adjacent installation of My Clean Days. My Clean Days was comprised of panels representing the ten years of Aylon’s marriage, on which the artist marked all the days throughout that decade in which she was “pure” and therefore permitted, according to halakah, to engage in sexual relations with her husband. Echoing Ukeles’s repetition of the words “immerse again” in her performance, Aylon stressed the repetitive aspect of the practice of ritual purification by concretizing it in the form of a calendar that marked the days of her “impurity” and “purity” over the course of her married life.72 Like Ukeles in Mikva Dreams, Aylon included a text in which she described the purification acts in the mikvah as an ancient female ritual connecting women to the lunar cycle. Moreover, and also like Ukeles, she opposed portraying the practice of immersion in terms of the pure-impure dichotomy. But, on a more critical note, Aylon stated in her text that “immersion . . . was an idea that had to come from a woman, not from those who do not bleed,” whereas “the term ‘unclean’ came from those who do not bleed.”73 Alongside her description of immersion as an ancient and exalted feminine ritual, she pointed to the patriarchal rabbinical system’s regulation of women. As she explained in reference to this installation, “It is my contention that ancient women founded the traditional bath long before Leviticus but were never credited for this. Instead, the concept of the bath was distorted by patriarchal rulings.”74 Aylon’s critical approach recalls Adler’s, who in the 1970s presented the rituals of immersion with sympathy, but later, in 1993, criticized the laws of nidda.75 While Aylon did not take a firmly critical position on the mikvah, she was, like Adler’s later stance, critical of the notion of purification as articulated by patriarchal Orthodox Jews. Comparing Ukeles’s works with those of Jewish American feminist artists clarifies the sympathetic nature of her approach to the Jewish ritual of purification and the unique manner by which she reclaimed this practice.

“The Personal is Political”: The Mikva Works in the Context of Maintenance Art

Ukeles’s treatment of the mikvah has received scant attention and remains in the shadow of her much better-known maintenance art. But examining these two groups of works in juxtaposition sheds new light on both bodies of work. Ukeles developed her mikvah works as part of her body of maintenance art. After the birth of her first daughter in 1968 and in response to the tension she experienced between her roles as an artist and as a mother, she composed the Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! in which she declared that she would henceforth perform all housework as art.76 She saw housework as “maintenance work,” a type of labor that society viewed as inferior to other forms of work.77

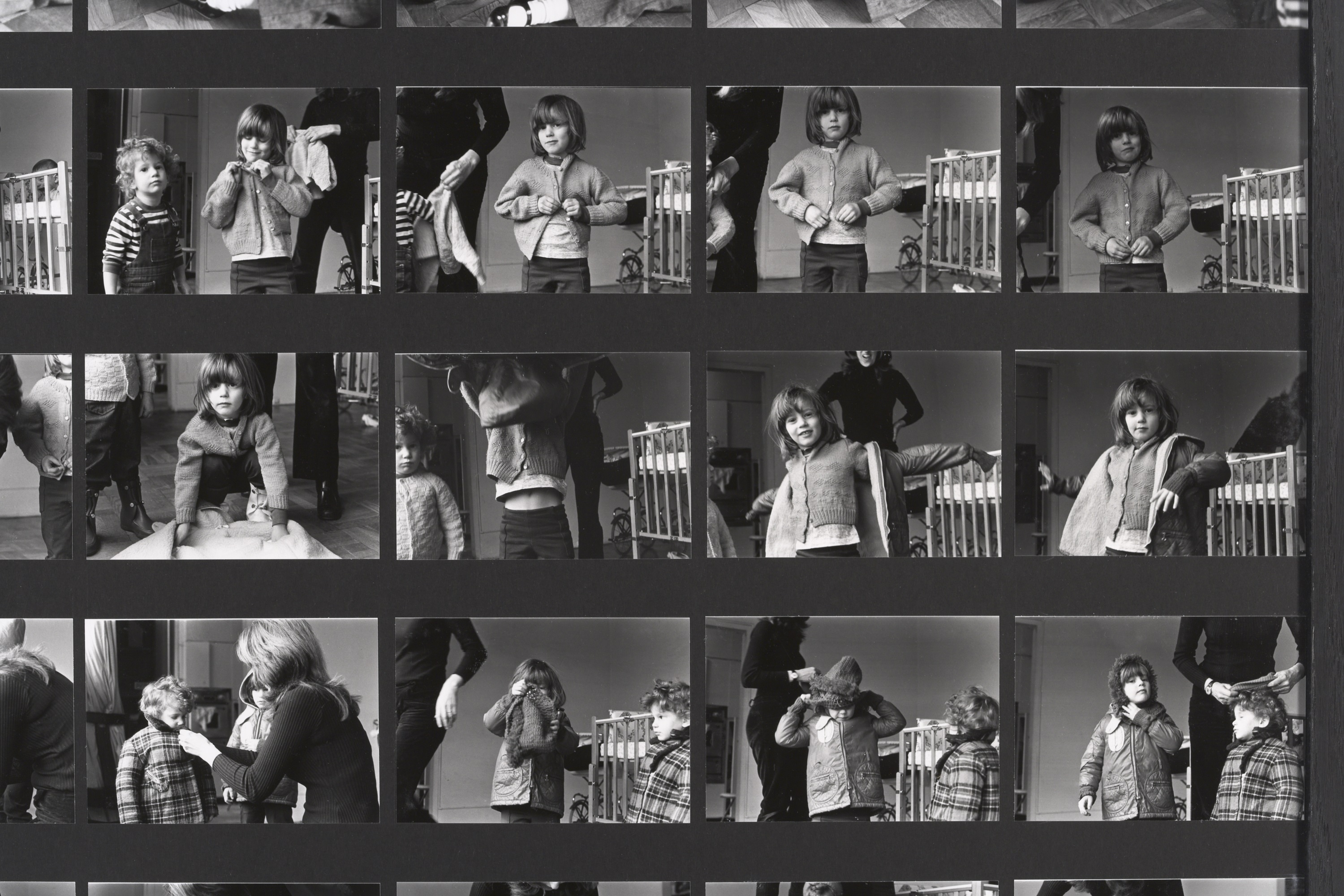

After writing the manifesto, Ukeles made several kinds of maintenance art. She documented several performances at home that make the transparent subjects of motherhood and housework visible. In one piece, she photographed herself cleaning a dirty diaper, thereby transforming private bodily excretion into art (fig. 18). In another, titled Dressing to Go Out/Undressing to Go In, she dressed and undressed her children, illustrating the considerable amount of women’s work required to transition them from the private home to the public sphere (fig. 19a, b).78 In her well known Maintenance Art Performance Series (1973–74), Ukeles featured herself washing museum floors and performing other cleaning jobs in an exhibition space, thereby connecting the daily drudgery associated with motherhood and managing a household with the centers of art (fig. 20).79 She expanded this feminist approach to other service jobs, including those typically performed by men who were viewed by society, like women, as second-class citizens.80 So, for example, the Touch Sanitation Performance (1978–80) was designed to give voice to people working in the devalued sanitation profession. In the performance, Ukeles set out to shake the hand of every single worker of the New York City Department of Sanitation as a gesture of thanks for the work they do for the city (fig. 21). As she greeted each of the 8,500 sanitation workers, Ukeles thanked them “for keeping NYC alive.” In each of these projects, Ukeles brought attention to the unseen and little-recognized labor that women, some museum employees, and sanitation workers perform regularly, investing it with a value that is ordinarily denied.

Maintenance art is rooted in Marxist feminism and the argument that women’s inferior economic status had led to their dependency on men, effectively rendering them nonautonomous beings.81 The solution offered in the 1960s was seemingly simple: women would gain independence by going out to work.82 And indeed, many feminists embraced this idea, eventually demanding equal pay for women in the work force. Feminists Marxists in the 1970s, however, demanded that the transparent labor of women (their various kinds of “care”) be recognized and validated by income as well.83 In this spirit, Ukeles did not rebel against women’s work per se, but instead argued that private work was no less important than public work, and housework was therefore worthy of remuneration. Transforming maintenance into art awarded it visibility and prestige; it was displayed in the public space of the museum and received respectful attention from curators, critics, and audiences. Her project underscored the inferior status accorded to maintenance work of all kinds and challenged the relegation of maintenance work to an invisible realm.84

Ukeles’s mikvah work is closely related to the rest of her maintenance art, first and foremost by the fact that both refer to notions of cleanliness. In fact, Ukeles saw all these works as forming part of a single cohesive artistic corpus. She performed Mikva Dreams at Franklin Furnace as part of a series entitled Maintenance Art Tales. In the 1980s, reflecting on her maintenance and mikvah work together, Ukeles explained that “as an artist, it is my job to make visible what usually is not so visible, to find value in everyday living—which, I feel, is a very Jewish idea.”85 Lisa Bloom claims that as in the artist’s maintenance work, which aimed to challenge the hierarchy of art and maintenance, so too does the artist’s treatment of ritual immersion underscore the sanctity of this practice and imbued it with prestige. According to Bloom, in contrast to the idea that immersion was designed to cleanse a woman of her impurities, Ukeles presented immersion as an exalted ritual act. In doing so, contends Bloom, the artist sought to situate immersion within the realm of the sacred.86

It is important to note that in the halakah, the significance of women’s immersion is indeed discussed primarily in terms of physical purity and impurity. In Judaism there are two types of immersions: one, designed for women, is performed for the sake of purification; the other is a symbolic immersion for the sake of Kedushah (holiness). This second is a custom performed by men, typically on the eve of the High Holidays or by men and women who are converting to Judaism.87 Whereas Biblical law did traditionally apply the terms of purity and impurity to men (indeed primarily to them), later rabbinical law freed men of the pure/impure categories and made them applicable only to women.88 Therefore, male immersion in the mikvah became optional, understood as an addition to sanctity, whereas a woman’s monthly immersion was obligatory, discussed primarily in terms of purification. In exalting the sacred aspects of women’s immersion in the mikvah, Ukeles was therefore challenging the devaluation of women’s rituals, just as her maintenance art challenged the devaluation of women’s labor in the home and the work of men cleaning the streets of New York.

Ukeles’s mikvah works are a crucial part of her broader preoccupation with institutional critique and her desire to undermine the division between public and private. Most importantly, in my view, Ukeles took a subject viewed as private and recast it as public. Presenting women’s ritual immersion to the public represented a radical departure from Jewish religious practice in the 1970s and 1980s, when the ritual was seen as a personal and intimate act that should remain invisible and was, moreover, never discussed in public. Ukeles looked back on this work in 2000, noted the silence surrounding nidda, and described her own work as set in sharp opposition: “You do not tell your family, you do not tell your children, you do not say where you are going [when going to the mikvah] . . . and here is the artwork, which gives me the permission to talk about anything.”89

At the same moment that radical feminists in the 1970s were arguing that the separation of private and public into two spheres had created a problematic hierarchy, Ukeles was placing a women’s private ritual into the public sphere. Associating men with the public and women with the private had effectively marginalized women and maintained them in positions of subordination.90 In her mikvah work, Ukeles rejected the relegation of the act of purification to the private invisible realm and instead presented it in public, exalting it as an empowering female rite.

In transferring women’s rituals from the private to the public sphere, Ukeles anticipated an important twenty-first century intellectual shift in Jewish feminist scholarship. For many generations, not only nidda and immersion but many other Jewish women’s customs and traditions were relegated to the private sphere as well. Hence, they were excluded from Jewish history and, in many cases, forgotten. As late as the 1990s, some historians still expressed the patriarchal view that women in traditional Jewish society did not take an active part in shaping the realm of culture, thereby justifying the exclusion of their religious life from historical research.91 But the general intellectual tide had in fact begun to shift a decade earlier with forceful feminist critiques by historians such as Joan Scott, who published her groundbreaking article, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis” in 1986.92 In this same spirit, feminist Jewish scholars began to show in the early years of the twenty-first century that Jewish women in past centuries led rich religious and spiritual lives, often engaging in religious activities with communal characteristics; indeed, women’s religious activities formed a kind of religion of their own, with unique rituals distinct from those of the men.93 By reclaiming women’s rituals and customs, these scholars sought to grant women a central role in contemporary Jewish culture. Ukeles was addressing themes in the late 1970s and 1980s that would only be raised later in Jewish feminist scholarship. Her mikvah performances and her installation at the Jewish Museum challenged the patriarchal structure of traditional Jewish society by reclaiming a women’s ritual as a religious feminist act. In so doing, she demonstrated that religion, feminism, and art are not as antithetical as some had claimed. At this crucial moment of second-wave feminism in the United States, her appropriation of female ritual immersion constituted a powerful call for women to be reborn as Jewish feminists.

Cite this article: David Sperber, “Mikva Dreams: Judaism, Feminism, and Maintenance in the Art of Mierle Laderman Ukeles,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1958.

Notes

This article expands a chapter of my doctoral dissertation, “Jewish Feminist Art in the U.S. and Israel, 1990–2017” (Hebrew). The dissertation was written under the guidance of Ruth E. Iskin from the Department of the Arts, Ben-Gurion University, in the Gender Studies Program, Bar-Ilan University, Israel. It was sponsored by the President’s Scholarship for Excelling Doctoral Students, Bar-Ilan University; The Rotenshtreich Fellowship for Outstanding Doctoral Students in the Humanities, and The Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture Doctoral Scholarship, New York. My thanks to Professor Iskin, the editors of Panorama, and the anonymous reviewers for their attentive reading of earlier versions of this article and their insightful suggestions. I am also grateful to the institutions that supported my work on this article as a postdoctoral associate: The David Hartman Center for Intellectual Leadership at the Shalom Hartman Institute, Jerusalem, and The Yale Institute of Sacred Music.

- Marisa Newman, “Art as Transformation: An Interview with Multi-Media Artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles,” Jofa Journal 6, no. 2 (2006): 15. ↵

- Samantha Baskind, Jewish Artists and the Bible in Twentieth-Century America (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014), 7. Baskind includes in her study George Segal (1914–2000), Larry Rivers (1923–2002), R. B. Kitaj (1932–2007), and Audrey Flack (b. 1931). ↵

- Sally M. Promey, “The Return of Religion in the Scholarship of American Art,” The Art Bulletin 85, no. 3 (2003): 583–85. ↵

- Promey, “The Return of Religion in the Scholarship of American Art,” 600n49. ↵

- Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avante-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985), 12. ↵

- Quoted in James Elkins and David Morgan, eds. Re-Enchantment (The Art Seminar) (New York: Routledge, 2009), 112. ↵

- James Elkins, On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art (London: Routledge, 2004). ↵

- Norman L. Kleeblatt, “Passing into Multiculturalism,” in Too Jewish? Challenging Traditional Identities (New York: The Jewish Museum in association with Rutgers University Press, 1996), 6. ↵

- Norman L. Kleeblatt, “Preface,” in Too Jewish?, x. ↵

- On the exclusion of Judaism from Jewish museums in the United States, see Ruth R. Seldin, “American Jewish Museums: Trends and Issues,” American Jewish Year Book 91 (1991): 71–117; Tom L. Freudenheim, “The Jewish Museum’s Discomfort with Religion,” Mosaic: Advancing Jewish Thought, May 30, 2019, https://mosaicmagazine.com/response/arts-culture/2019/05/the-jewish-museums-discomfort-with-religion. ↵

- Holland Cotter, “An Artist Redefines Power. With Sanitation Equipment,” New York Times, September 15, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/16/arts/design/an-artist-redefines-power-with-sanitation-equipment.html. ↵

- Lucy R. Lippard, “Never Done: Women’s Work by Mierle Laderman Ukeles,” in Patricia C. Phillips, Tom Finkelpearl, Larissa Harris, and Lucy R. Lippard, Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art (New York: Prestel, 2016), 20. ↵

- Patricia C. Phillips, “Making Necessity Art: Collisions of Maintenance and Freedom,” in Phillips et al., Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art, 65, 70, 74–80. ↵

- Ukeles published the text for Mikva Dreams in “Mikva Dreams—A Performance,” Heresies: The Great Goddess 5 (1978): 52–54. ↵

- Ukeles, “Mikva Dreams—A Performance,” 53. ↵

- Ukeles, “Mikva Dreams—A Performance,” 52–53. ↵

- Ellen M. Umansky and Dianne Ashton, “Part IV. 1935–1989: Urgent Voices,” in Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality: A Sourcebook, ed. Ellen M. Umansky and Dianne Ashton (Boston: Beacon Press, 1992), 192. ↵

- Ukeles, “Mikva Dreams—A Performance,” 52–54. ↵

- Mierle Laderman Ukeles to the author, March 17 and 19, 2019. Unless otherwise noted, all information provided by Ukeles about her work derives from this email correspondence. ↵

- Mierle Laderman Ukeles, “Mikva Dreams—A Performance (1978),” Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality, 234–37. ↵

- Umansky and Ashton, “Part IV. 1935–1989,” 192. ↵

- Newman, “Art as Transformation,” 15. ↵

- Mierle Laderman Ukeles, “Mierle Laderman Ukeles (Artist’s Statement),” Jewish Themes/Contemporary American Artists II (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1986), 48. ↵

- Ukeles to the author, March 17 and 19, 2019. ↵

- Ukeles, “Artist’s Statement,” in Jewish Themes, 48. ↵

- Mierle Laderman Ukeles, “The Place of Kissing Waters” (artist’s statement), 1986 (unpublished), 2, collection of the artist. ↵

- Lisa E. Bloom, Jewish Identities in American Feminist Art: Ghosts of Ethnicity (New York: Routledge, 2006), 54–55. ↵

- Ukeles, “The Place of Kissing Waters,” 4. ↵

- Newman, “Art as Transformation,” 16. ↵

- Michael Brenson, “Bringing Fresh Approaches to Ages-Old Jewish Themes,” New York Times, August 3, 1986, A27. ↵

- Lynne Rosenthal, “Contemporary Artists Explore Jewish Themes,” New York City Tribune, July 28, 1986, 12. ↵

- Phillips, “Making Necessity Art,” 80. ↵

- Newman, “Art as Transformation,” 15. ↵

- On the feminist spirituality movement, see Cynthia Eller, Living in the Lap of the Goddess: The Feminist Spirituality Movement in America (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 38–61. ↵

- Gloria Feman Orenstein, The Reflowering of the Goddess: Contemporary Journeys and Cycles of Empowerment (New York: Pergamon, 1990), 34–71; Jennie Klein, “Goddess: Feminist Art and Spirituality in the 1970s,” Feminist Studies 35, no. 3 (2009): 575–602. ↵

- Josephine Withers, “Feminist Performance Art: Performing, Discovering, Transforming Ourselves,” in The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact, eds. Norma Broude and Mary Garrard (New York: Harry Abrams, 1994), 158–73; Tal Dekel, Gendered: Art and Feminist Theory (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2013), 51. ↵

- Dekel, Gendered, 23–24; “Performance Art,” The Art Story, https://m.theartstory.org/movement-performance-art-history-and-concepts.htm. ↵

- Klein, “Goddess,” 583. ↵

- Wendy Griffin, “The Embodied Goddess: Feminist Witchcraft and Female Divinity,” Sociology of Religion 56, no. 1 (1995): 46. ↵

- Ukeles, “Mikva Dreams—A Performance,” 52. ↵

- Cynthia Eller, “Divine Objectification: The Representation of Goddesses and Women in Feminist Spirituality,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 16, no. 1 (spring 2000): 29. ↵

- Eleanor Heartney, “Bad Girls,” in The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium, eds. Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal, and Sue Scott (Munich: Prestel, 2013), 15–23. ↵

- Amelia Jones, “Sexual Politics: Feminist Strategies, Feminist Conflicts, Feminist Histories,” in Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party in Feminist Art History, ed. Amelia Jones (Berkeley: UCLA at the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center in association with University of California Press, 1996), 20–38; Rachel Middleman, Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018). ↵

- Jeanie Forte, “Women’s Performance Art: Feminism and Postmodernism,” Theatre Journal, 40, no. 2 (1988): 217–35. ↵

- Leslie C. Jones “Transgressive Femininity: Art and Gender in the Sixties and Seventies,” in Abject Art: Repulsion and Desire in American Art, Selections from the Permanent Collection (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1993), 33–58. ↵

- Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality (London and New York: Routledge, 1992); Helena Reckitt, “Personalizing the Political,” in Art and Feminism, ed. Helena Reckitt (London: Phaidon, 2001), 97. ↵

- Quoted in Claudette Lauzon, The Unmaking of Home in Contemporary Art (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017), 34. ↵

- Laura Meyer, “Power and Pleasure: Feminist Art Practice and Theory in the United States and Britain,” A Companion to Contemporary Art Since 1945, ed. Amelia Jones (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 322. ↵

- Linda Weintraub, “Carolee Schneemann,” in Art on the Edge and Over: Searching for Art’s Meaning in Contemporary Society, 1970s–1990s (Litchfield, CT: Art Insights, 1996), 165–70. ↵

- Withers, “Feminist Performance Art,” 161–63. On the work Interior Scroll, see also Nead, The Female Nude, 67; Amelia Jones, Body Art/Performing the Subject (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), 3; Reckitt, “Personalizing the Political,” 82. ↵

- Weintraub, “Carolee Schneemann,” 169. ↵

- Meyer, “Power and Pleasure,” 317–42. ↵

- Linda Montano, Performance Artists Talking in the Eighties: Sex, Food, Money/Fame, Ritual/Death (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 457. ↵

- Ukeles, “Mikva Dreams—A Performance,” 52. ↵

- Mary F. Zawadzki, “Listen to the Words of the Great Mother: The Goddess Art of Mary Beth Edelson,” Journal of American Culture 39, no. 3 (2016): 336. ↵

- Ronit Irshai and Tanya Zion Waldoks, “Ha-feminism ha-ortodoxy-ha-moderni be-yisrael: bein nomos le-narativ,” (Modern Orthodox Feminism in Israel: From Nomos to Narrative), Mishpat u-mimshal 15, no. 1/2 (2013): 247n21 (Hebrew). ↵

- Irshai and Waldoks, “Ha-feminism ha-ortodoxy-ha-moderni be-yisrael: bein nomos le-narativ,” 247n21. ↵

- Ukeles, “Mikva Dreams—A Performance,” 52. ↵

- Rachel Adler, “Tum’ah and Taharah: Ends and Beginnings,” in The Jewish Woman, ed. Elizabeth Koltun (1973; reprint, New York: Schocken Press, 1976), 63–71. ↵

- Blu Greenberg, “The Mikvah,” in Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality, 314. ↵

- See Bloom, Jewish Identities, 3; Matthew Baigell, Jewish-American Artists and the Holocaust (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 103; Baigell, American Artists, Jewish Images (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 153–54. ↵

- Susan Gubar, “Eating the Bread of Affliction: Judaism and Feminist Criticism,” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 13, no. 2 (1994): 293–316. ↵

- Kleeblatt, “Passing into Multiculturalism,” 5–6; Bloom, Jewish Identities, 22–23, 84–85. ↵

- Ellen M. Umansky, “Feminism and the Reevaluation of Women’s Roles within American Jewish Life,” in Women, Religion and Social Change, eds. Yvonna Yazbeck-Haddad and Ellison Banks-Findly (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985), 478; Joyce Antler, Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women’s Liberation Movement (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 9, 315–48. ↵

- Edna Kantorovitz Carter Southard, review of Jewish Identities in American Feminist Art: Ghosts of Ethnicity by Lisa E. Bloom, Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary Journal 5, no. 1 (2007): 2, http://wjudaism.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/wjudaism/article/view/3159/1303. ↵

- Newman, “Art as Transformation,” 16. ↵

- See Mac McCloud, “History as Renewal,” in Weisberg Prints: Mid-Life Catalogue Raisonne, 1961–1990, eds. Ruth Weisberg and Gary M. Ruttenberg (Fresno, CA: Fresno Art Museum, 1990), 24–25. ↵

- Matthew Baigell, “The Scroll in Context,” in Ruth Weisberg: Unfurled (Los Angeles: Skirball Cultural Center, 2007), 16; and Bloom, Jewish Identities, 22–23, 84–85. ↵

- Arlene Raven, “WOMANHOUSE,” in The Power of Feminist Art, 61. This performance was recorded and appears in the documentary film Womanhouse, by Johanna Demetrakas, 1974. The Getty Research Institute, 2896–034. ↵

- Baigell, “The Scroll in Context,” 16. ↵

- See Ruth Weisberg, “A Life in Art (2),” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies and Gender Issues 7 (2004): 231–32; Debra J. Byrne, “A Conversation with the Artist,” Heightened Realities: The Monotypes of Ruth Weisberg (Seattle: Frye Art Museum and Hemlock Printers, 2001), 17. ↵

- Aylon’s work is reminiscent of an earlier work by Schneemann, Blood Work Diary, 1972, and is also close in spirit to Post-Partum Document by Mary Kelly (b. 1941), 1973–79, which intricately charts the artist’s relationship with her son and her changing role as a mother. ↵

- Helène Aylon, Whatever Is Contained Must Be Released: My Jewish Orthodox Girlhood, My Life as a Feminist Artist (New York: The Feminist Press at The City University of New York, 2012), 51. ↵

- Helène Aylon, “My Bridal Chamber”: “My Marriage Bed”/“My Clean Days” (2014), video, 3:25, https://www.heleneaylon.com/my-bridal-chamber-my-marriage-bed-m. ↵

- Rachel Adler, “In Your Blood Live: Re-visions of a Theology of Purity,” Tikkun 8, no. 1 (1993): 38–41. On Adler’s changed view regarding the mikvah, see Mary Farrell Bednarowski, The Religious Imagination of American Women (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), 39–41. ↵

- A link to the full version of the Maintenance Art Manifesto appears on the exhibition page for Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art (September 18, 2016–February 19, 2017), Queens Museum: https://queensmuseum.org/2016/04/mierle-laderman-ukeles-maintenance-art. ↵

- Tom Finkelpearl, “Interview: Mierle Laderman Ukeles—On Maintenance and Sanitation Art,” in Dialogues in Public Art, ed. Tom Finkelpearl (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 301–3. ↵

- These works echo works by other feminist artists of the time, such as Sandra Ogel’s Ironing (1972; Womanhouse), Christine Rush’s Scrubbing (1972; Womanhouse) and Martha Rosler’s video Semiotics of the Kitchen (1974–75). ↵

- In a similar way, Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document, 1973–79, focused on motherhood and the domestic experience of childcare. ↵

- Julia Kristeva suggested viewing “femininity” as a socially constructed position and not a straightforward definition of gender at this same time. According to Kristeva, femininity is that which the patriarchal symbolic order pushes to the margins. See Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language, trans. Margaret Waller (1973; reprint, New York: Columbia University Press, 1984). ↵

- See Heidi I. Hartmann, “Capitalism, Patriarchy, and Job Degregation by Sex,” Signs: Women and the Workplace: The Implications of Occupational Segregation 1, no. 3 (1976): 137–69. For an examination of the connections between maintenance art, Marxist discourse, and feminist Marxism, see Helen Molesworth, “Work Stoppages: Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Theory of Labor Value,” Documents 10 (1977): 19–22; Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 19–23; Shannon Jackson, Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics (New York: Routledge, 2011), 75–103. ↵

- See, for example, Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: Norton, 1963), 15–32. ↵

- Rosemarie Tong, Feminist Thought: A Comprehensive Introduction (London: Routledge, 1989), 51–60. ↵

- See Molesworth, “Work Stoppages.” For more on maintenance art as institutional critique, see Julia Bryan Wilson, “A Curriculum for Institutional Critique, or the Professionalization of Conceptual Art,” in New Institutionalism, ed. Jonas Ekeberg (Oslo: Office of Contemporary Art, Norway, 2003), 89–109; Jackson, Social Works, 75–103; Christine Wertheim, “After the Revolution, Who’s Going to Pick Up the Garbage?,” X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly 12, no. 2 (2009): 13–21; Helena Reckitt, “Forgotten Relations: Feminist Artists and Relational Aesthetics,” in Politics in a Glass: Case Feminism, Exhibition Cultures and Curatorial Transgressions, eds. Angela Dimitrakaki and Lara Perry (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013), 107–22. ↵

- Quoted in Phyllis Ellen Funke, “Facets of Jewish Art,” Hadassah Magazine (October 1986): 47. ↵

- Bloom, Jewish Identities, 52. ↵

- See Daniel Sperber, Minhagei Yisrael (Jewish Customs) 2 (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 2001), 185–88 (Hebrew), and Minhagei Yisrael 4 (2005): 298–99 (Hebrew). ↵

- Niza Yanay and Tamar Rappoport, “Nationalism and Niddah: The Women’s Body as a Text,” in Will You Listen to My Voice? Representations of Women in Israeli Culture, ed. Yael Atzmon (Tel Aviv: Hakkibutz Hamuachad, 2001), 213–15 (Hebrew). ↵

- Bloom, Jewish Identities, 52. ↵

- See Ruth Gavison, “Feminism and the Public/Private Distinction,” Stanford Law Review 45, no. 1 (1992): 1–45; Tracy E. Higgins, “Reviving the Public/Private Distinction in Feminist Theorizing,” Chicago-Kent Law Review 75, no. 3 (2000): 847–67; “The Logic of Gender: On the Separation of Spheres and the Process of Abjection,” Endnotes 3, special issue, Gender, Race, Class, and Other Misfortunes (2013), https://endnotes.org.uk/issues/3/en/endnotes-the-logic-of-gender. ↵

- See Jacob Katz, in Katz and Chava Weissler, “On Law, Spirituality and Society in Judaism: An Exchange between Jacob Katz and Chava Weissler,” Jewish Social Studies 2, no. 2 (1996): 87–115. ↵

- Joan Wallach Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (1986): 1053–75. ↵

- See, for example, Varda Polak Sahm, The House of Secrets: The Hidden World of the Mikva (Ben Shemen: Modan, 2005), 122–58 (Hebrew); Yemima Hovav, Maidens Love Thee: The Religious and Spiritual Life of Jewish Ashkenazic Women in the Early Modern Period (Jerusalem: Magnes & Carmel Press, 2009) (Hebrew); Aliza Lavie, Women’s Customs: A Feminine Mosaic of Customs and Stories (Tel Aviv: Yedioth Ahronoth, 2012) (Hebrew). ↵

About the Author(s): David Sperber is a Fellow at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music