The Architects of Reconstruction: Alcès Family Portraits as Emblems of Afro-Creole Leadership

Editors’ Note: Due to unanticipated institutional closures because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the author was unable to secure permission to reproduce three of the four images for this essay.

The period of Reconstruction gave Creoles of color a broad national platform to campaign for universal male suffrage and equality for all men, regardless of race or former station. A class of assertive and vocal Afro-Creole leaders emerged almost immediately after the fall of New Orleans to the Union in April of 1862. From the outset, this group agitated for participation in the Union army, emancipation of slaves, and enfranchisement of all men of color. Because of their long history of political agitation within Louisiana, Creoles of color were in a unique position within the American South for their role in the vanguard of this new political movement. They were wealthy, which allowed them to fund newspapers that served as organs of the radical Republican movement in Louisiana, and their strong ties to prominent members of the white Creole community further legitimized their cause and formed an interracial movement. Finally, their multicultural upbringing and education made this group literate, articulate, and able to apply examples from American, French, and Haitian history to buttress their claims to equality. It is not surprising, then, that with Afro-Creoles from New Orleans at the helm, Reconstruction began first, lasted longer, and went farther in Louisiana than in any other Southern state. In fact, early on, Abraham Lincoln referred to Reconstruction as “the Louisiana experiment.”1

The artistic production and patronage of the Creole of color community in Reconstruction-era New Orleans must be understood within this context. Afro-Creoles emerged as outspoken leaders of the radical Republican political faction. Their determination to achieve the equality they had been fighting for since 1803 was clearly articulated in the essays and poems that filled their newspapers—L’Union (1862–64) and La Tribune de la Nouvelle-Orléans/New Orleans Tribune (1864–68).2 These newspapers became the official mouthpieces of Louisiana’s Republican Party by employing an international worldview to argue for abolition and civil rights. Contributors to L’Union and the Tribune used their knowledge of history and of recent events in France and the French Caribbean to infuse their writings with a strong and unapologetic political stance. Reconstruction presented this group with the opportunity to overtly express protest and demand long-sought civil rights.3

A pair of pendant portraits of Georges Alcès (1870, Louisiana State Museum; fig. 1) and his wife, Elizabeth Alice Briot Alcès (1870, Louisiana State Museum; fig. 2) by the French artist François Bernard (1812–1875)—a leading portrait artist in late nineteenth-century New Orleans—are emblematic of the Afro-Creole leadership caste at the forefront of battles over Reconstruction in Louisiana. Although there is no evidence that Georges Alcès (1840–1913) himself was involved in Reconstruction politics, his education, career, and background were similar to the Creole of color leaders of the movement. Like his antebellum predecessors and contemporary Creole activists, Alcès deliberately chose to patronize a French academic painter and have the portraits made in the French Neoclassical style, in order to provide visual confirmation of his family’s right to equality. By comparing the Alcès pendant portraits to a contemporary portrait of a white Creole, also by Bernard; a photograph of an Afro-Creole political leader in New Orleans; and a poem written by a New Orleans Creole of color during this period, I will illustrate how the Alcès portraits fit into the contemporary visual landscape of New Orleans. More specifically, I will show how the Alcès family utilized portraiture as an advertisement of their wealth and elite status among their close associates, as well as a strong political statement that insisted on New Orleans Creoles of color’s readiness for enfranchisement. In this way, the Alcès portraits can be regarded as visual counterpoints to the agitation of Afro-Creole writers and politicians during the Reconstruction period.4

François Bernard, the painter responsible for the Alcès family portraits, was probably born in Nîmes, France around 1812. He began his artistic career as a student at the Académie des Beaux Arts in Paris, where he trained with Paul Delaroche (1797–1856). He exhibited at the Paris salons between 1842 and 1849, before traveling to New Orleans in 1856. Like many of his French colleagues of the previous generation, such as Jean-Joseph Vaudechamp (1790–1866) and Jacques Amans (1801–1888), Bernard was renowned for his portraits, genre scenes, and landscapes, and he was in great demand among wealthy Louisiana patrons. He spent falls and winters at his art school and studio in New Orleans, where he probably executed the majority of his portraits. During springs and summers, he worked as an itinerant painter, returning to France or traveling around Mandeville, Louisiana (just north of Lake Pontchartrain), painting ethnographical studies of local indigenous groups like the Choctaw. Bernard left New Orleans after the outbreak of the Civil War, returning in 1867, and then he immigrated to Peru in 1875. It was during his final period in New Orleans, in 1870, that Georges and Elizabeth Alcès commissioned him to paint their pendant portraits.5

The oval bust-length portraits feature the prominent Creole of color cigar manufacturer, Georges Alcès, and his wife, Elizabeth Alice Briot Alcès (1841–1941). Georges is seated and facing his left, painted against a hazy, dark green landscape backdrop. He is positioned in a three-quarter view, but he gazes directly out at the viewer with an intense expression. He is olive-skinned, with slicked-back dark hair, a mustache, and a small bit of facial hair beneath his chin. He has high cheekbones, a straight nose, and serious dark eyes. He is outfitted in a fashionable but austere black suit and tie, with only a gold pocket watch chain as embellishment. The dark background and dark clothing focus the viewer’s attention primarily on Georges’s face; his erect posture, direct gaze, and stern expression make him appear haughty.

The dark green landscape background, oval canvas, mirrored three-quarter view, and bust-length pose link Georges Alcès’ portrait to that of his wife, Elizabeth Alice Briot Alcès. As in Georges’s portrait, these elements spotlight Elizabeth’s face and demeanor. Unlike Georges, however, his wife’s expression is more approachable and her costume more elaborate. Elizabeth is depicted with very light skin, dark eyes, and dark hair that is styled in an elaborate and fashionable updo. She has a pleasantly round face and looks directly at the viewer, but her expression is softened by a slight smile. She is wearing a stylish, well-tailored, and expensive-looking black dress with cap sleeves and a boat neck, trimmed in rows of black lace. Over the dress, she wears a sheer black lace-trimmed jacket. While Georges’s only accessory is his watch chain, Elizabeth wears several pieces of chic jewelry, such as ruby and gold drop earrings, a gold brooch, a gold belt buckle at her waist, and a gold chatelaine.

Together, these portraits depict a fashionable and wealthy young couple. The clothing, jewelry, upright postures, and cultured facial expressions convey the elite status of the sitters. Furthermore, the fact that these portraits were commissioned in 1870 is an additional indicator of the affluence and status of the sitters, because after 1850, painted portraits were increasingly rare among the middle class due to the rise of photography, a much more convenient and inexpensive option for self-representation.6 By 1870, painted portraiture was predominantly commissioned by only the wealthiest patrons, corroborating the elevated status of the Alcès family.

The extant information regarding Georges Alcès’ life and career also indicates that his family was socially elite and wealthy. Alcès was one of the largest cigar manufacturers in Louisiana, and at the height of his business he employed more than two hundred workers.7 Alcès originally went into business with his uncle, Lucien “Lolo” Mansion, who owned an extremely prosperous tobacco manufacturing company on Orleans Avenue in the Faubourg Tremé.8 Alcès expanded the family business by opening his own tobacco factory, also in the Tremé. He was such a prominent figure within the Creole of color community in New Orleans that the Afro-Creole historian Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes (1849–1928) included a brief biography of Alcès in the chapter recounting the lives of Creole of color philanthropists in his 1911 book Nos Hommes et Nôtre Histoire. Alcès was one of five prominent and wealthy Afro-Creole businessmen discussed in the chapter, which also included the prominent Radical Republican activists Thomy Lafon and Aristide Mary. All of these men were praised by Desdunes for their altruistic activities, especially toward fellow Creoles of color. Desdunes described Alcès as a wealthy and successful entrepreneur who was generous to his employees, all of whom were Creoles of color. Desdunes also states that Alcès’s business was under attack in the late 1860s, when a slick competitor opened a tobacco factory nearby and enticed many of Alcès’s employees to leave. Although Desdunes did not clearly indicate the race of Alcès’s business rival, it can be inferred that the competitor was white because of the way Desdunes only references the man by “Mr. C_____.” Desdunes’ reluctance to name the villain in Alcès’s story would have been necessary at the time of the book’s original publication in 1911 in the midst of the ascendancy of Jim Crow laws enforcing segregation. Desdunes recalled that, as the promises of Reconstruction faltered and fell, black businessmen and property owners were increasingly vulnerable to white community members who were determined to strip free people of color, who had come to be a large and powerful community, of their remaining rights. Desdunes suggested that Alcès felt betrayed by the defection of his employees and was disillusioned with his place in New Orleans, and that this was therefore why he moved his family to New York City “sometime after the Civil War.”9

Alcès commissioned the pendant portraits while his business was under attack, perhaps as a reminder of his high social status. While the class of the Alcès family is clearly legible within these pendant portraits, the race of the sitters is less apparent. In fact, the expression of wealth and status within the portraits, as well as the couple’s physical appearance, costume, and bearing, may have led viewers to assume that the subjects were white, because the cost of the commission would have been out of reach for most African Americans in 1870. Georges and Elizabeth Alcès were Creoles of color; however, their portraits do not include any clear markers of race, such as dark skin color, broad features, or stereotypical qualities often attributed to black people in nineteenth-century American visual culture. Bernard steers clear of any negative caricatures in the Alcès portraits, empowering his sitters to defy contemporary racist logic. Instead, Bernard relies on French academic naturalism to carefully render the appearance and personalities of the two sitters. The absence of racial iconography within these portraits keeps viewers focused on the Alcès’s performance of elite status, which, in New Orleans, sometimes crossed racial boundaries. This is significant because it underscores the fact that race was not the defining feature of the Alcèses, or indeed any of the Creole of color elite—it was not the most prominent or remarked-upon identifying factor of this caste. Instead, wealth, status, and education superseded race and were the markers by which they insisted upon being characterized.

The emphasis on class rather than race in the Alcès portraits becomes more evident when compared with earlier portraits of white sitters executed by Bernard in New Orleans. For example, Bernard’s bust-length portrait of Mme. Alcée Villere (c. 1858, Historic New Orleans Collection; fig. 3) is stylistically similar to the 1870 portrait of Elizabeth Alcès. In the oval-shaped canvas, Mme. Villere (1834–1890), who was from a prominent white Creole family, faces the viewer frontally. She is posed against a dark backdrop, focusing the viewer’s gaze on her face and figure. Mme. Villere has dark hair and eyes and is elaborately costumed in a white lace off-the-shoulder dress trimmed with a pink satin ribbon along the neckline. Additionally, she wears a bracelet on each wrist and a diamond ring on her right hand. Her right arm is crossed across her waist, while she reaches up to touch her face with her left hand, animating the portrait. Although the frontal pose and hand gestures in Mme. Villere’s portrait divert from the more restrained three-quarter pose and erect posture of Elizabeth Alcès, the ovular format; the slight, warm smile; and the ostentatious display of fashionable clothes and expensive jewelry connect these portraits across racial boundaries. In fact, Villere’s coloring and facial features are not appreciably different from those of Elizabeth Alcès. The phenotypic similarity between the two women highlights the ambiguity and confusion endemic to the racial landscape of nineteenth-century New Orleans, where it was often difficult to differentiate between white and black Creoles.

In many ways, portraiture further blurred the problem of distinguishing between the two racial groups. Since white and black Creoles often patronized the same artists and had their portraits made in the same French academic style, it is often impossible to make a distinction between the two groups by visual evidence alone.10 Indeed, I believe that it may have been the intention of Afro-Creole subjects like the Alcèses to directly confront and challenge Anglo-Americans’ conceptions of race and class with their portrait commissions. In patronizing the same artists, utilizing the same artistic styles, and highlighting the similar phenotypes shared by white and black Creoles, Afro-Creoles could disrupt the neat fictions of dominant American racial ideologies. These portraits became visual records of the constant slippage between racial castes in New Orleans, in the same way that the wealth, prosperity, and education of Creoles of color was a continuous reminder of this phenomenon within the social sphere of New Orleans society in daily life.

The choice by Creoles of color, such as Georges and Elizabeth Alcès, to commission portraits in French academic styles by French-trained artists is further evidence of the close ties between Creoles across racial boundaries. Like their white counterparts, black Creoles’ first language was French; they often traveled extensively or studied abroad in France; and they were familiar with French history, literature, and art. In addition, Creoles of color utilized these portraits to assert their equal wealth and social status to their white Creole counterparts. By patronizing the same artists and employing the same representational styles, Creoles of color were able to link themselves visually to the white Creole elite. This connection was a visible reminder within the family home—and within the larger Creole of color community—of the economic and social status and achievements of Creoles of color, like the Alcèses. The self-confidence and material success illustrated by these portraits are evidence of Afro-Creoles’ assurance in their own abilities as equal to those of their white neighbors’, despite the ubiquitous counternarratives espoused by the dominant white culture that equated African ancestry with inferiority. In this way, the Alcès portraits function as compelling visual statements of equality within the private and public spheres.

Such portraits serve as a visual counterpart to the political demands for legal and social equality voiced by New Orleans Creoles of color during the Reconstruction era. However, the most active and vibrant stage for the highly vocal Afro-Creole political protest in Reconstruction New Orleans was the press. Creoles of color used the press to openly express their political stance. It was through the press that New Orleans Creoles of color emerged as leaders within the Black community and were simultaneously able to enact their role as cultural mediators between the disparate racial, cultural, and political factions within Reconstruction Louisiana and the nation.11

Creoles of color staked their claim in the political press immediately after the Union occupation of New Orleans. In September of 1862, Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez (1823–1890), a Creole of color physician who had earned his degree in Paris during the 1848 Revolution (in which he participated), bankrolled the French-language political newspaper, L’Union. At first written primarily in French, in 1863 it became a bilingual newspaper, including a short English-language section meant to cater to Anglo-Americans within New Orleans. Paul Trévigne (1825–1908), a Creole of color and language teacher at a school founded by and for free people of color, served as the editor of the paper and established its radical position from the very first edition. In the premier issue, Trévigne published an editorial entitled “Slavery” on the front page, which blasted the institution of slavery and the slaveholding South.12 Trévigne expressed not only his insistence on the immediate abolition of slavery but also his belief in universal male suffrage. Therefore, during the very beginnings of the Civil War itself, New Orleans Creoles of color were using the local press to formulate their political position and actively shape the format of Reconstruction. They were in the vanguard, demanding rights and political access that were not available even to most people of color in the North, much less in the slaveholding South. They seized upon the Union occupation of New Orleans as an opportunity to agitate for equal rights and inclusion.13

As politically radical as L’Union was, it was short-lived and, ultimately, a failure in achieving its goals. Although the contributors to L’Union were overt in their calls for abolition and universal male suffrage, their audience was necessarily limited because of the language barrier of the journal. The majority of the newspaper was in French, with only a small English-language section. L’Union was therefore written by and for Creoles of color and French-speaking white radicals. Instead of uniting Republicans across language, racial, and cultural lines, it alienated the Anglo-American community and suggested that Creoles of color were an exclusionary group.

Despite L’Union’s shortcomings, the journal was extremely important in establishing the local and national political position of Creoles of color and negotiating the concerns of black New Orleanians in the early years of Reconstruction. L’Union also established the interracial connections sought and fostered by Creoles of color. In 1863, the journal added the Belgian-born radical Jean-Charles Houzeau (1820–1888) to its editorial staff. In the same year, L’Union became the official organ of the Union Association of New Orleans, a radical political group that included white Creoles, Creoles of color, and European-born men who were committed to Louisiana’s readmittance into the Union, the abolition of slavery, and the full enfranchisement of all black men. Finally, L’Union was able to establish national links between the radical political faction in Louisiana and those in the North. For example, L’Union made important connections with two New York newspapers: the antislavery French-language newspaper, Messager Franco-Américain, and Horace Greeley’s The New York Tribune. Both journals hailed the political stance expressed by the editors of L’Union and expressed solidarity with the journal.14

As important as L’Union was to the political landscape of early Reconstruction in New Orleans, it was in L’Union’s successor, La Tribune de la Nouvelle-Orléans/The New Orleans Tribune, that the political and cultural stance of Creoles of color reached its zenith. L’Union disbanded in 1864, and one week later, the paper reorganized and began publication as the New Orleans Tribune.15 The Tribune maintained Trévigne and Houzeau on its editorial staff and was also bankrolled by Louis Charles Roudanez. However, the Tribune was, from the outset, a truly bilingual publication, with the French portion translated completely into English. Moreover, it amped up its publication schedule and printed daily rather than weekly editions. As such, the Tribune has the distinction of being the first black daily newspaper in the United States.16 In its overt radical political stance and deliberate cultivation of support across racial and cultural boundaries, The Tribune allowed Creoles of color to take on the mantle of African American leaders for the first time. It not only expressed the political interest of Creoles of color in equality for all Americans of African descent, but, because it was published in both French and English, the journal also self-consciously reached out to like-minded activists beyond the local Creole community. Furthermore, the paper reiterated its political position as the voice of African Americans through its physical location. In 1865, the Tribune relocated its offices to 122–24 Exchange Alley in the French Quarter. This site held symbolic significance because it was a pedestrian walkway linking the French Quarter to Canal Street, thought to be the dividing line between the Creole section of the city (the French Quarter) and the Anglo-American sector (upriver from Canal Street). Finally, the location was directly across from the St. Louis Hotel, which contained one of the most active and well-known slave exchanges in the antebellum South. By placing the Tribune’s offices there, editors reclaimed the location as a site of agitation for abolition and black equality rather than for the oppressive slave system, all while positioning themselves as mediators between Creoles and Anglo-Americans.17

The Tribune’s politics were audacious. The paper actively cultivated a multicultural, multiracial staff, including Creoles of color, the European-born editor Houzeau, and non-Creole black staff members. The content of the Tribune urged Americans to look beyond the borders of the United States in imagining a new nation. Furthermore, the journal advocated for the interests and enfranchisement of all African Americans. While this decision forced Afro-Creoles to adhere to the rigid racial categories of the American racial binary, they compromised in order to negotiate for the social and political admittance of all black men into the new American order. This maneuver was important because it called attention to race itself as a construct. If Creoles of color could choose their racial identity, especially when they often did not physically fit the bill, such a choice negated the idea of the fixity of race. The fluidity of race—an idea long established in association with Louisiana’s Creoles of color—was used by the Tribune as another tool to negotiate universal male suffrage.18

Besides news reportage and editorials, the Tribune published poems. These poems were remarkable because they used a French Romantic style to critique the local political landscape of Louisiana. Just as Romanticism had been used in French literature and art to rally the public in support of revolution and envision a new political order, Creole of color poets similarly used Romanticism to unify the public and imagine a new racial order in Louisiana. Caroline Senter describes the importance of the work accomplished by these poets in her essay “Creole Poets on the Verge of a Nation”:

The writers aggressively entered the contemporary debate over nation and race from the unique perspective their Creole experience afforded them: as citoyens under French rule, participants and/or supporters of the French Revolution, and descendants of and/or correspondents with Creoles of color in independent Haiti. The Creole poets employed radical literary traditions from the French and Haitian Revolutions to address the possibilities and circumstances of Reconstruction, using the medium of the newspaper to imagine with readers a nation of composite citizenry, an unprecedented United States.19

In this way, Creole poets adapted a dominant French style for their particular political agenda, just as Creole patrons like the Alcèses had for their portraiture. Moreover, these poets relied on the international worldview of Creoles of color to support their social and political goals. In doing so, they were able to engage not just national but also international debates over abolition and black suffrage. The publication of such poems and their adherence to a French literary styl, reiterated the in-between place of Creoles of color in New Orleans society, flanked by white Creoles, Anglo-Americans, and African Americans. While the poems refer to the histories and cultural modes of France and Haiti familiar to New Orleans Creoles, they were also translated into English, giving Anglo-Americans access.

In 1867, the Tribune published “La Marseillaise Noire,” a poem by a Creole poet using the pseudonym Camille Naudin. In the introduction, Naudin explains that the poem was inspired by a song from the play Toussaint L’Ouverture by the French Romantic author Alphonse de Lamartine. This reference to the martyred hero of the Haitian Revolution would have been unheard of prior to Reconstruction, when an 1830 law prohibited the publication of material that could incite Louisiana’s people of color. However, in 1867 Naudin boldly references the Haitian revolutionary and simultaneously positions himself within the context of French Romanticism, carefully crafting links between Louisiana Creoles (the community to which he belonged) and French and Haitian cultural and political movements, thus underscoring the hybrid culture of New Orleans Creoles of color. The poem was published only a few months after the 1867 Louisiana spring elections, in which forty-nine blacks and forty-nine whites were elected to the state legislature.20 Naudin captures the optimism of this moment in the opening stanza of the poem, writing:

It is the solemn hour!

Where over the old overthrown world

A faltering despotism

Comes to crown liberty.21

Naudin credits the multiracial Republican alliance for the political progress and rights gained through Reconstruction, stating:

That in a sainted alliance

Blacks and Whites having condemned

To death ancient abuse

Walk full of confidence.22

Finally, Naudin reiterates the emptiness of phenotype in favor of universal equality, noting:

It is intelligence and soul

And no longer the skin makes the man.23

This poem illustrates the global context of Creoles of color, with its references to France and Haiti, and suggests that political progress can only be gained through cross-racial alliance, linking Creoles of color with African Americans.

The bold and outspoken political commentary of the Tribune was instrumental in the passage of the Louisiana Constitution the following year. This state Constitution was the most radical in the United States, in that it provided all African Americans with full equality, including voting rights; desegregated public schools, transportation, and businesses; and legalized interracial marriage. Unfortunately, 1868 also marked the ascendency of a faction of moderate Republicans, who worked to oust radicals, primarily black and white Creoles, from political power, just as they began to make compromises with Louisiana conservatives. Three years later, Roudanez suspended the publication of the Tribune due to financial difficulties.24

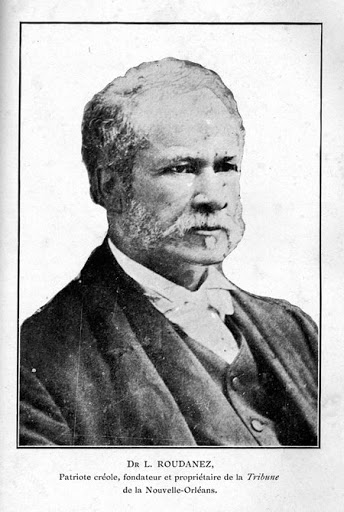

During the period of Reconstruction, the Alcès portraits worked in similar ways to Afro-Creole journalism: they reference French stylistic precedents and underscore the hybrid culture of New Orleans Creoles of color. A comparison of the portrait of Georges Alcès with a photograph of Roudanez demonstrates that both men also presented themselves similarly in visual representations (fig. 4). The photograph is a three-quarter-view bust portrait against a blank backdrop, emphasizing Roudanez’s face and personality. His gaze is piercing, and his expression is serious. He avoids all ostentation in his choice of a plain, though fashionable, suit. The photograph highlights Roudanez’s position as a physician, a political activist, and a publisher by showcasing his serious demeanor. Georges Alcès’s portrait from the same period straddles the line between the seriousness of Roudanez’s photograph and the flamboyance of a formal painted portrait. Alcès’s expression is stern, and his gaze is direct, just as in Roudanez’s photograph, positioning him in his role as an important businessman and community leader. But Alcès’s decision to commission a formal oil portrait, as opposed to a less expensive photograph, might also serve to craft his image as a businessman, since his business acumen led to the wealth that enabled him to afford such a commission. Roudanez, as an activist, and one who willingly sank his savings into his political publications, would not have had the same need for a painted portrait to signal his wealth or social standing.

By selecting French artist François Bernard as their portraitist, the Alcès family opted to be depicted using French portrait conventions, which focus viewers’ attention on the faces, and therefore personalities, of the sitters. In employing this French academic style for depictions of Creoles of color who do not physically appear to be black, such portraits demonstrate the multicultural and international worldview of Creoles. These choices fundamentally operate to call American racial ideology into question. Simultaneously, while the portraits seem to obscure traditional markers of race, the subjects of both the Alcès portraits and the Roudanez photograph openly acknowledged their racial affiliations. Georges Alcès and Louis Charles Roudanez spent their lives advocating for the enfranchisement of black New Orleanians—Roudanez as a Reconstruction-era leader of the African American community and Alcès through his policy of hiring and assisting black employees in his cigar factory. In this way, such portraits exemplify the Afro-Creole leadership class during Reconstruction and highlight their global identity. More significant, perhaps, such works of art bring attention to the ways in which the racial and cultural malleability of New Orleans Creoles of color both bridged the gap between different cultural groups in New Orleans and called into question the primacy of the racial ideology that was at the very center of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Despite the ultimate failures of Reconstruction, it lasted in Louisiana until 1877, longer than in any other Southern state.25 More importantly, Reconstruction allowed Creoles of color to apply their wealth, education, and international worldview to the local and national political stage. They used the opportunities presented by Reconstruction to vocalize their radical politics and position themselves as African American community leaders. Furthermore, they gained concrete experience in civil rights agitation, which they continued to utilize through the late nineteenth century—culminating in French-speaking Creole of color Homer Plessy’s challenge to Louisiana’s segregation laws, as plaintiff in the staged Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896.

Cite this article: Wendy Castenell, “The Architects of Reconstruction: Alcès Family Portraits as Emblems of Afro-Creole Leadership,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10123.

PDF: Castenell, Architects of Reconstruction

Notes

- Ted Tunnell, Crucible of Reconstruction: War, Radicalism, and Race in Louisiana, 1862–1877 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984), 35. ↵

- Caryn Cosé Bell, Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana, 1718–1868 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997), 223–24. ↵

- Justin A. Nystrom, “Racial Identity and Reconstruction: New Orleans’ Free People of Color and the Dilemma of Emancipation,” in The Great Task Remaining Before Us: Reconstruction as America’s Continuing Civil War, ed. Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010), 125–26. ↵

- The term “Afro-Creole” is anachronous to the period of nineteenth-century Louisiana. Prior to about 1900, all Creoles referred to themselves simply as Creoles, with no reference to their racial designation. The term was used to indicate the culture of an individual—the fact that they had some Gallic ancestry, spoke French as their primary language, and were baptized Catholic—with no differentiation made between Creoles of full European descent and those with some African ancestry. It was only in the twentieth century that racial identifiers like “Creole of color” or “Afro-Creole” began to commonly be used to distinguish black and white Creoles. I have chosen to use this contemporary terminology so as not to confuse readers. See Carl L. Bankston III and Jacques Henry, “The Socioeconomic Position of the Louisiana Creoles: An Examination of Racial and Ethnic Stratification,” Social Thought and Research 21, no. 1/2 (1998): 259, and Sybil Kein, “Use of Creole in Southern Literature,” in Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana’s Free People of Color (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 156. ↵

- François Bernard Artist File, The Historic New Orleans Collection (HNOC), New Orleans, LA. ↵

- Miles Orville, American Photography (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003), 21–23. ↵

- Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes, Our People and Our History: Fifty Creole Portraits, trans. Sr. Dorothea Olga McCants (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1973), 90. ↵

- Sally Kittredge Evans, “Free Persons of Color,” in New Orleans Architecture Volume IV: The Creole Faubourgs, ed. Roulhac Toledano, Sally Kittredge Evans, and Mary Louise Christovich (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 1974), 34. ↵

- Desdunes, Our People and Our History, 90–91. Desdunes did not give an exact date for Alcès’s departure from New Orleans, nor does any other source on Alcès. The portrait’s date of 1870, and the fact that François Bernard was still active in New Orleans at this time, however, suggest that Alcès was still a resident of the Crescent City at that time and moved to New York at some point after 1870. ↵

- François Bernard Artist File, HNOC. The records in Bernard’s artist file clearly illustrate that, while the majority of his portrait commissions were from white European American sitters, he was hired by patrons of many races and ethnicities. ↵

- Shirley Thompson, Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 227. In this book, Thompson argues that free people of color in New Orleans held an ambivalent position within society, which she describes as the group’s “in-between-ness.” This liminal position, however, also put them in the position of being cultural mediators, and to serve as liaisons between competing cultural factions. It was, in fact, this mediating position, along with their radical politics and international world view that allowed Afro-Creoles to fill the power vacuum and emerge as the leaders of Radical Reconstruction in Louisiana. ↵

- Paul Trévigne, “L’Esclavage,” L’Union, September 27, 1862. ↵

- Bell, Afro-Creole Protest Tradition, 223. ↵

- Bell, Afro-Creole Protest Tradition, 239–45. ↵

- Bell, Afro-Creole Protest Tradition, 248. ↵

- Laura V. Rouzan, “Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez: Publisher of America’s First Black Daily Newspaper,” South Atlantic Review 73, no. 2 (2008): 54–58. ↵

- Thompson, Exiles at Home, 217–18. ↵

- Caroline Senter, “Creole Poets on the Verge of a Nation,” in Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana’s Free People of Color, ed. Sybil Kein (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 277. 282–83. ↵

- Senter, “Creole Poets,” 277. ↵

- Bell, Afro-Creole Protest Tradition, 275. ↵

- Camille Naudin, “La Marseillaise Noire,” La Tribune de la Nouvelle-Orléans, June 17, 1867. ↵

- Camille Naudin, “La Marseillaise Noire,” quoted in Senter, “Creole Poets,” 291. ↵

- Naudin, quoted in Senter, 291. ↵

- Bell, Afro-Creole Protest Tradition, 277. ↵

- Foner, Reconstruction, 538. ↵

About the Author(s): Wendy Castenell is Assistant Professor of Art History and African American Art at The University of Alabama