On Patriotism

“What a thing is patriotism! We go for years not knowing we have it. Suddenly—Martial music! . . . Native flags! Friends cheer! . . . and it becomes life’s greatest emotion!” King Vidor’s statement accompanies the opening frames of his silent film masterpiece, The Big Parade—his look at the Great War, but I think it accurately describes where we as Americans are as we head into the autumn of 2017, suddenly drawn into vehement fights that we did not see coming over patriotic displays in the public square and on the football field. What a thing is patriotism, indeed, that the emotion can so easily overtake and divide us.

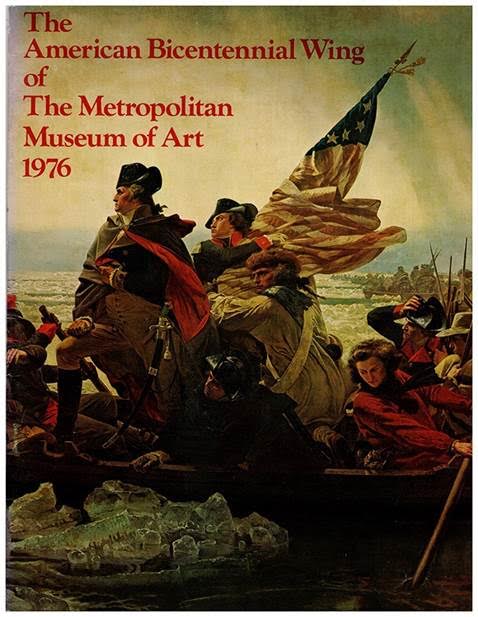

But one intensely patriotic moment in our time proved a watershed for our field. I entered museum work in the Bicentennial summer of 1976, when the federal government, through a network of regional offices and corporate underwriters, provided significant funds to museums for American art exhibitions as suitably patriotic displays—the examination, from coast to coast, and in myriad ways, of our collective history and creativity—efforts that would honor and speak to a country’s revolution. The goal was to build broad interest among the population in the celebrations, but the result was as well an outpouring of research and scholarship in American art to meet the amped-up programs of museums in anticipation of enthusiastic crowds. American art historians owe much to that moment of patriotic fervor, which supported the building of a solid foundation for the future growth of a field of study. The government and corporate largesse was enough to make many of our institutions suddenly willing to dust off collections that had little place in the old hierarchies of world art until then. Fine scholarship came out of what was a dedicated effort to encompass the country as a whole. Despite the governmental imprimatur and corporate sponsorship, much of the work was not at all jingoistic. Bicentennial exhibitions and their catalogues surveyed what were then rarely published collections, such as the city monuments of Cincinnati, the art and artisans of Philadelphia, the holdings of the Alaska State Museum, and an ambitious survey produced by the Whitney Museum of American Art, Two Hundred Years of American Sculpture. The sweeping Bicentennial Inventory of American Paintings was launched to record works in public and private collections across the country―this expansive database is invaluable, used by scholars still from around the world. The range of topics essayed in the Bicentennial projects was surprisingly diverse, which is evident as I scan the list of some sixty Bicentennial publications in my museum library, including Amistad II: A Bicentennial celebration for all, inspired by the struggle of a few, organized by David Driskell to survey two centuries of African American art for a national tour featuring the Fisk University collection; and The American Indian, The American Flag, an extensive catalogue on Native American art and its complicated imagery of patriotic symbols, published by the Flint Institute of Arts for a show that toured widely. The Cleveland Museum produced its landmark and sweeping exhibition and publication The European Vision of America, and in Washington, D.C., the Hirshhorn Museum mounted The Golden Door: Artist-Immigrants of America to show that the United States has always offered sanctuary to immigrants and refugees and to celebrate the contributions they made to artistic innovation and to the national cultural fabric.

Patriotism proved to be an effective force in building an audience for American art in 1976, and we enlist it still for that purpose. We can mark upticks in museum attendance that conform to patriotic times. We did not plan for it, but in the weeks and months after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, museums became places of solace, and American art served to offer a sense of community. In this climate, Childe Hassam’s American flag paintings took on a different, melancholy air: The Magazine Antiques and the New York State Council on the Arts both chose the Hassam painting from the Amon Carter Museum for publication as the most eloquent emblem of a grieving nation. “We stand for you and with you,” American art museums are saying to patriots once again. Each summer since 2010, American Blue Star Museums have offered free admission to active-duty military personnel and their families from Memorial Day to Labor Day.

On Inauguration Day 2017, the Seattle Art Museum (where I serve as curator), like so many others, opened its doors free of charge to all, and legions poured in. Patriots all, each concerned in their own way for the welfare of their country. Can patriotism ever help us to see the country as a whole? I would make the case that patriotism has effectively showed American art museums the way to engage diverse audiences, and in that process, it has played a part in directing us as curators and educators to a deeper understanding of the United States and a greater appreciation for its complex cultural landscape.

Cite this article: Patricia Junker, “Bully Pulpit” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1613.

About the Author(s): Patricia Junker is the Ann M. Barwick Curator of American Art at the Seattle Art Museum.