Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s

Curated by: Gianni Jetzer with curatorial assistance from Sandy Guttman

Exhibition schedule: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, February 14–May 13, 2018

Exhibition catalogue: Gianni Jetzer, Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s, exh. cat. New York and Washington, DC: Rizzoli Electa and Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 2018. 192 pp.; 154 color illus. Hardcover $55.00 (ISBN: 9780847862412)

After ascending the Hirshhorn Museum escalator to visit Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s, one sees David Robbins’s small bronze plaque Prop (1987) first. Robbins’s work bears the message that greets visitors to Disneyland, notifying them that “Here you leave today and enter the world of yesterday, tomorrow and fantasy.” In the context of Brand New: Art and Commodity, curated by the Hirshhorn Museum curator-at-large Gianni Jetzer, the appropriated text portentously announces entry to a world as foreign as tomorrow and fantasy: the wilds of the 1980s. An investigation of advertising, managerial habits, and the consumption of technological products serve as the organizing concept for this exhibition, presented primarily through works by artists working in New York City between 1979 and 1989, and across painting, sculpture, photography, video, printed graphics, and related ephemera. As the latest high-profile exhibition to dive into the no-longer-so-recent past of the 1980s, Brand New: Art and Commodity is an uneven survey that too often strikes an ambivalent attitude toward the cultural, political, and, yes, even commercial engagements of the works on view.

In recent years, museums have newly attended to the art of the 1980s, and, in particular, the art of the 1980s in the United States, as temporal distance allows for critical distance. Becoming commonplace are single-medium shows, thematically organized surveys, and retrospective exhibitions of artists whose careers, despite extending beyond the decade, are tied to the ascent of the blue chip galleries, the so-called East Village scene, or a culture of protest of specific political regimes or social crises (such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz, and Martin Wong).1 A New York City focus is frequently adopted, although usually more explicitly signaled than in Brand New: Art and Commodity.2 Perhaps the most comprehensive and geographically inclusive of these recent explorations of the decade has been Helen Molesworth’s sweeping This Will Have Been: Art, Love, & Politics in the 1980s, organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2012.3

Jetzer’s exhibition is narrower in scope than This Will Have Been, but it might be the optimal exhibition for the present moment. With a government that seems overrun by 1980s supervillains leveraging political influence for economic profit, it seems timely to examine a not-so-distant past when greed was good and technology promised salvation from totalitarian ideologies (Ridley Scott’s 1984 [1983] for Apple Inc. is on view in the exhibition). As Jetzer explains in his catalogue essay, the exhibition title is intentionally “ambivalent in nature, yoking two words that were immanent in both art and commerce in the 1980s. . . . As both advertising and art came to rely more on concepts and ideas than on tangible characteristics, the two fields converged to an unprecedented degree.” By the end of the decade, many artists who sought to subvert market strategies and habits of conspicuous consumption, Jetzer argues, “were ultimately digested by a capitalist system that transformed them and their artistic production into creative capital.”4

Although galleries are ordered in a loose chronology, brief wall texts indicate secondary organizing themes, such as: The Artist as Brand; From the Studio to the Office; Hygiene and Contamination; and Product Placement. These themes, however, depart from the titles accompanying the chronologies in the exhibition catalogue: “DIY: 1979–1982”; “The New Capital: 1983–1986”; and “Dissemination and Contamination: 1987–1989.” These conflicting schemas render the exhibition and catalogue as almost separate treatments of the same subject using the same examples. More than fifty artists and collectives are represented, with close to gender parity. However, few works by artists of color are included, such as Adrian Piper’s charcoal drawing Vanilla Nightmares #8 (1986), Tishan Hsu’s porcelain and rubber Biocube (1988), Ken Lum’s Untitled Furniture Sculpture (1980–present; courtesy of the artist) and Alex Gonzalez Loves His Mother and Father (1989), and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1987–90). In this context, Robbins’s Talent (1986), eighteen black-and-white headshots of nineteen artists (the duo Clegg and Guttmann share a photograph), reinforces an “artworld so white” view of the decade.

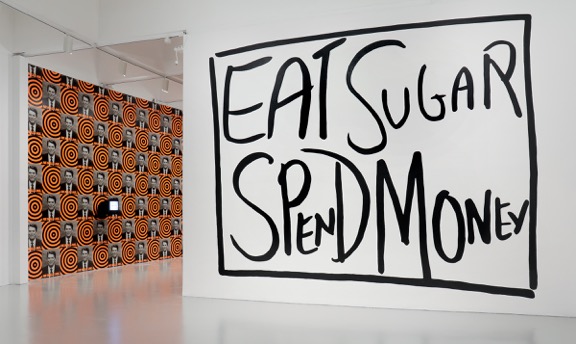

Artists engaging a product-driven culture populate the exhibition galleries. Dara Birnbaum’s Remy/Grand Central: Trains and Boats and Planes (1980), commissioned by the cognac retailer and shown in the New York City terminal, plays in the same gallery as Peter Halley’s Pepsi Please (1980) hangs, a painting of a ghoulish figure captioned by the title of the work. General Idea’s dollar sign–shaped The Boutique from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavilion (1980) is overloaded with gift shop–type memorabilia. Walter Robinson’s painted still life Lube Landscape (1985), Haim Steinbach’s shelf of detergent boxes and ceramic pitchers, supremely black (1985), and David Wojnarowicz’s painting on a supermarket poster, USDA Choice Beef (1985) mine the vocabulary of contemporary advertising and product design. Gretchen Bender’s Dumping Core (1984) intercuts the logos of television networks and car companies with news footage and clips of the Statue of Liberty across thirteen video monitors to a thrumming synthesizer and percussion soundtrack. Stripping away coded messaging, Jennifer Diamond’s T.V. Telepathy (Black and White Version) (1989; courtesy of the artist) fills a gallery wall, directing viewers in bold black lettering to “Eat Sugar” and “Spend Money” (fig. 1).

The exhibition features some predictable artists and works. The large black-and-white hand of Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (I shop therefore I am) (1987) presents a business card with the title message of the work. Two Guerilla Girls lithographs critique the limited representation of women artists by commercial galleries. Ashley Bickerton’s Tormented Self-Portrait (Susie at Arles) No. 2 (1988), speckled with logos for media companies, tobacco products, and clothing retailers, hangs on one gallery while a wall of Jenny Holzer’s rainbow-printed Inflammatory Essays (1979–82) greets viewers in another. Photographs by Sarah Charlesworth, Cindy Sherman, and Richard Prince are on view, as are a suite of Jeff Koons’s late-decade sleek Art Magazine Ads (1988–89) and his billboard-size New! New Too! (1983; private collection) (fig. 2). The walls of one corridor are papered with Mike Bidlo’s Not Warhol (Cow Wallpaper, 1966) (1984; courtesy of the artist and Galerie Bruno Bischofberger), against which is hung Warhol’s four-panel Self-Portrait (1986; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden). Projected opposite is Tom Warren’s digitized slides of Bidlo’s Mike Bidlo Presents: The Factory at PS1 (1984; Tom Warren Portrait Studio), in which the artist dons Andy Warhol drag while others wear costumes of denizens of Warhol’s Factory, presented to exhibition visitors as an appropriation of an artist’s brand through persona and entourage (fig. 3).

Artists often left out of recitations of canonical figures are welcome inclusions, complicating an exhibition that too easily could have relied upon a display of “greatest hits.” Julia Wachtel’s large paintings Love Thing (1983) and what, what, what (1988) highlight popular culture gender objectification. Wachtel is also one of the few artists whose work is accompanied by an artist’s statement. Alan Belcher’s serial Fence Posts (1987) and Gun (1987), as well as Joel Otterson’s Devil/Jesus (1986) tower of copper pipes overtaking a table, are significant sculptural inclusions, placed in the middle of galleries. One gallery is almost entirely devoted to the work of R. M. Fischer. His monumental Elbow Macaroni Lamp (1979) looms large in a corner, and a press release-cum-manifesto and promotional video for his lamp sculptures, produced by Carol Ann Klonarides and Michael Owen of MICA-TV, are shown nearby.

Some sly curatorial gestures are also to be found. John M. Armelder’s Untitled (1986; Museum of Modern Art), chrome and vinyl chairs placed on either side of rectangular white canvas, finds a visual echo in Meyer Vaisman’s The Stretch Painting (1986; collection of B.Z. + Michael Schwartz). They are hung adjacently, with the erect verticality of the former clearly recognized alongside the flaccid forms of the latter. Lum’s Untitled Furniture Sculpture, four loveseats, side tables, and lamps, form a fortified enclosure against visitors. His self-contained living room also transforms Allan McCollum’s Hydrocal Surrogate paintings, Peter Nagy’s visual timeline Entertainment Erases History (1983; courtesy of the artist and Magenta Plains), Sherrie Levine’s Chair Seat 5 (1986; courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner), and Philip Taaffe’s Undercurrent (1984; collection of the artist) into over-the-couch art (fig. 4). This installation plan rewards close looking as it evacuates the surrounding paintings of their cool conceptualism. By emphasizing the decorative banality of these works, the move also strangely animates these paintings anew.

A pair of vitrines gesture at the entrepreneurial spirit of artists: establishing collectives, creating market-ready products, and offering consultation services. Ephemera and multiples from Fashion Moda and Colab are indicative of engagement with affordable art for a mass public, while business cards, project statements, and announcement flyers by The Offices of Fend, Fitzgibben, Holzer, Nadin, Prince &Winters (comprised of Peter Fend, Colleen Fitzgibbon, Jenny Holzer, Peter Nadin, Richard Prince, and Robin Winters) document white-collar professionalization of and as artmaking. Louise Lawler and Sherri Levine’s business cards, matchbooks, and circulated announcements document strategies of institutional critique, targeting the big business of art business. As with many of the works in the exhibition, these materials are only limitedly contextualized by wall text, although these two vitrines are more fully unpacked in the insightful catalogue essay by Leah Pires.5

Historical amnesia falls over the exhibition in certain places. Claes Oldenburg might object to the assertion of one wall text that Stefan Eins “was one of the first to experiment with the form of the art ‘store’ (as opposed to ‘gallery’) with his 3 Mercer Street storefront space from 1972 to 1979.” References to precedent cooperative galleries and artist-driven marketing experiments of the Tenth Street Galleries of 1950s and 1960s are also missing. Jetzer’s catalogue essay sketches a selective chronology of commodities as “crucial vessels for ideas,” drawing a “direct line of development from Duchamp” through Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Warhol to the works in the exhibition.6 Yet even this abbreviated survey betrays the promotional bluster of the exhibition, which drew attention to the “unique trends” and “unique collaborations” on which the show is premised.7

Also unclear is the gallery organized around a theme of “Political Activism.” The gallery contains Erika Rothenberg’s Freedom of Expression Drugs (1989), a display of packaged products such as Protest Pills and Anti-Apathy Ointment, and Krysztof Wodiczko’s Homeless Vehicle, Variant 5 (1988–89), a mobile shelter providing security and autonomy for its users in order. As works responsive to the insidious effects of corporate takeovers of both space and citizenship, these works are comfortably paired. Without its optional pendant painting, Sherrie Levine’s Ignatz: 6 (1988) offers an opaque comment. Wall text elliptically explains that the painted Krazy Kat figure, depicted as having just thrown a brick, “both inspires and houses social desires and hopes” and “encapsulates the tragicomedy of our relationships with objects.” Does Jetzer intend for audiences to puzzle over this work, a sign of violence without weapons, as an attack without argument? Is it a comment on protest in a world saturated by commodities? Are we meant to read this as illuminating or tamping down the influence of the works not only surrounding but preceding it? After exiting a gallery papered in Donald Moffett’s He Kills Me (1987; International Center of Photography) and Gretchen Bender’s continuously broadcasting Untitled (People with AIDS) (1986; courtesy of the Gretchen Bender Estate and OSMOS) (fig. 1), how should we understand the framing of Levine’s work as “political activism”?

The AIDS crisis is addressed elsewhere in Robert Gober’s Three Parts of an X (1985), Alan Belcher’s $51.49 (1983), and Gran Fury’s Silence = Death (1987; New Museum), the latter installed apart from the main circumference of the exhibition galleries. This neon sign is hung on the first floor, facing out toward the museum courtyard, an installation likely intended to model the work’s original display as part of Let the Record Show . . . .8 Rather than contributing to a multimedia indictment of the Reagan administration’s inaction and demonization of the AIDS crisis and those affected by it, the Hirshhorn Museum’s display of the work is toothless. Given its location, the glare on the glass, and the dominating form of the escalators crisscrossing behind it, Silence = Death can be too easily overlooked by those approaching the building. It is also mostly hidden from those inside the museum, visible only within the narrow corridor between the escalators and the windows, a viewing position that would reverse the letters of the sign (fig. 5). It is possible that the placement is meant as curatorial commentary on the ease of overlooking the ongoing disease. Yet, through its disconnected placement, the work is also transformed into just another sign, just another visible representation of the 1980s that advertises the exhibition to those on the outside of the building looking in. This is the risk of subsuming politically pointed historical works of art within an exhibition about brands and commodities. Particularly as we live through the perverse 1980s redux of the present moment, when slogans such as “protest is the new brunch” circulate on apparel, and general calls to “resist” occlude the necessary work of focused political action, we should be careful not to reduce critical cultural engagement to a #brand.

Cite this article: Andrew Wasserman, review of Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1676.

PDF: Wasserman-review-of-Brand-New

Notes

- Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s, Whitney Museum of American Art, January 27–May 14, 2017; Physical: Sex and the Body in the 1980s, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, March 20–July 31, 2016; Basquiat, Brooklyn Museum, March 11–June 5, 2005; Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks, Brooklyn Museum, April 3–August 23, 2015; Basquiat Before Basquiat: East 12th Street, 1979–1980, Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, February 10–May 14, 2017; Keith Haring: 1978–1982, Brooklyn Museum, March 16–July 8, 2012; David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake At Night, Whitney Museum of American Art, July 13–September 30, 2018; and Martin Wong: Human Instamatic, Bronx Museum of the Arts, November 4, 2015–March 13, 2016. ↵

- East Village USA, New Museum, December 9, 2004–March 19, 2005; The Times Square Show Revisited, Hunter College Art Galleries, September 14–December 8, 2012; Urban Theater: New York Art in the 1980s, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, September 21, 2014–January 4, 2015; Club 57; Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village, 1978–1983, Museum of Modern Art, October 31, 2017–April 8, 2018. ↵

- This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s was shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, February 11–June 3, 2012; Walker Art Center, June 30–September 30, 2012; and Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, November 15, 2012–March 3, 2013. ↵

- Gianni Jetzer, “Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s” in Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s (New York and Washington, DC: Rizzoli Electa and Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 2018), 20, 35. ↵

- Leah Pires, “Please/Function: Aesthetic Services Circa 1980” in Brand New: Art and Commodity, 62–73. Pires also curated one of these two vitrines. ↵

- Jetzer, “Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s,” 22–24. ↵

- “Hirshhorn Announces First-Ever Exhibition to Focus on Art and Commodity in the 1980s,” Newsdesk (October 26, 2016): https://newsdesk.si.edu/releases/hirshhorn-announces-first-ever-exhibition-focus-art-and-commodity-1980s. Art historians, gallerists, and critics noted these omissions in response to Tyler Green (@TylerGreenDC), “‘Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s’…” Tweet, December 13, 2017: https://twitter.com/TylerGreenDC/status/941050585393930240. ↵

- Let the Record Show . . . , New Museum, New York, November 20, 1987–January 24, 1988. ↵

About the Author(s): Andrew Wasserman is Visiting Assistant Professor at the School of Art, University of North Carolina at Greensboro