A Portrait on the Move: Photography, Literature, and Transatlantic Exchanges in the Nineteenth Century

As a fellow in the Conservation Division of the Library of Congress during the summer of 2015, I worked with Adrienne Lundgren, senior conservator of photographs, on a project to catalogue the photographs tipped into nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photography manuals and periodicals in the library collections. We came across numerous rare and Research Note–worthy photographs, but I will focus here on two versions of a photograph both titled Portraitstudie (figs. 1, 2). Although the portrait itself is typical of the era, it caught my attention because it was one of several prints that appeared in photography periodicals published on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The print was featured first in the German photography journal Photographische Mitteilungen in November 1871 (fig. 1), and then it reappeared eight months later to United States readers in The Philadelphia Photographer (fig. 2). The transatlantic crossing of this print (and others like it) led me to reconsider two significant features of histories of early photography in the United States: their national focus and emphasis on origins.

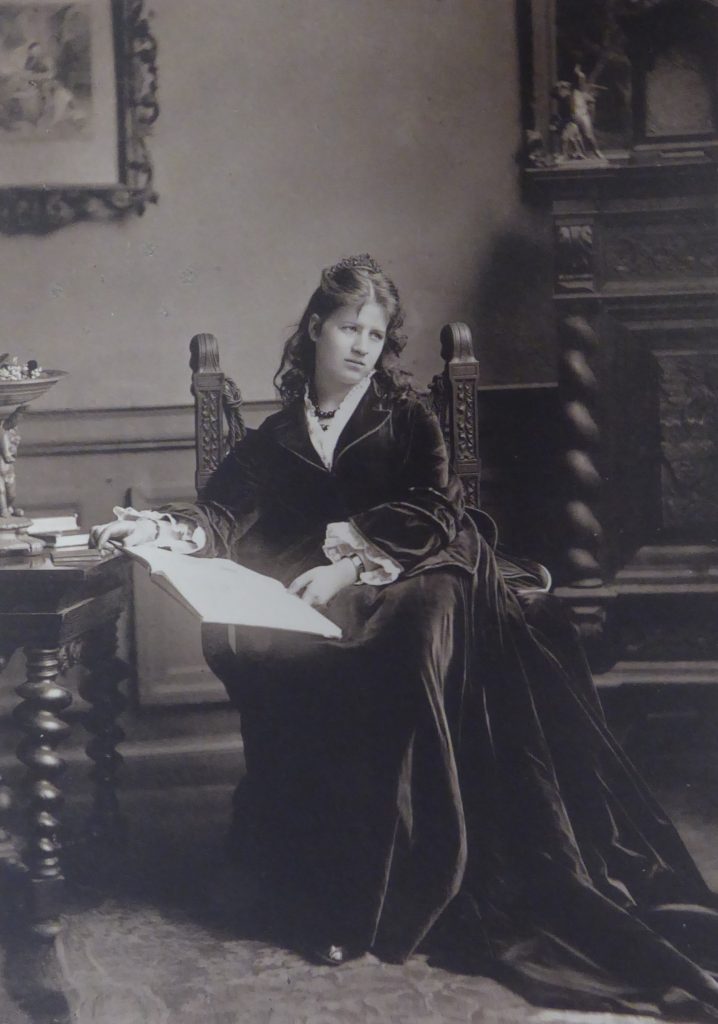

The negative for the Portraitstudie prints was created by the firm of Loescher and Petsch, a fashionable photography studio in Berlin. Their portrait shows a young woman robed in a voluminous dark gown that spreads in precise folds along a carpeted floor. She is posed in a refined studio setting populated by dark, sculptural furniture and looks up from a large album whose white glow obscures our knowledge of its contents. Both prints are collotypes, a form of photomechanical printing, and were made by Munich-based inventor Johann Baptiste Obernetter. Photomechanical print processes, in which an ink-on-paper print is produced from a photographic negative, comprised a relatively new category of printing during this period that excited the interest of photographers and scientists because they made photography more compatible with the printing press, as will be discussed.1

The prints also differ in noticeable ways, although they were printed from the same negative with the same process. First, the version that appeared in the Philadelphia Photographer is slightly larger in size to accommodate the greater size of the journal. The American version was also printed from the negative differently and shows more of the Loescher and Petsch studio, perhaps to allow readers a better view of the fashionable Renaissance Revival furnishings that earned praise in Germany.2 Finally, the inversion of the print in The Philadelphia Photographer is a result of the mechanics of the collotype process. Despite these variances, American readers were able to view the print and judge its merits on similar terms as their German colleagues.

The passage of the Portraitstudie images and their role as carriers of knowledge between photographers working across the Atlantic Ocean unsettles aspects of the conventional history of early photography in the West. As the familiar narrative usually goes, the world learned of the invention of photography in 1839. First came the announcement of the daguerreotype process, developed by Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833) and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) in France, and then came news of the photogenic drawing process developed by William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) in England. With their announcements, the workings of these early processes began to travel to various parts of the globe. Following this initial moment of excited international circulation, however, many histories of nineteenth-century photography then turn to focus on the flourishing medium in isolated national contexts.3 This is certainly true of my own area of specialization, early photography in the United States, where international exchanges typically appear only in the preface to histories of the medium. An examination of the movements and reception of Portraitstudie calls into question two main features of this conventional narrative: the tendency to frame early histories of photography in national terms and the emphasis on firsts that pervade technical histories of the medium. The pair of Portraitstudie images instead suggest that international exchanges and collaborations were central to the development of photography well beyond the initial flurry of activity around 1839.

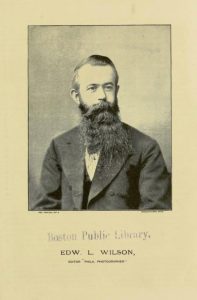

The periodicals in which the two Portraitstudie images appeared, Photographische Mitteilungen and The Philadelphia Photographer, were vital to the domestic and international circulation of photographic knowledge in the nineteenth century. These and similar periodicals functioned as virtual laboratories that enabled the testing of ideas between photographers often working at great distances from one another. Beginning publication in the 1850s, early photography journals featured chemical recipes, equipment designs, criticism, and tipped-in photographic prints. Prominent journals such as Photographische Mitteilungen and The Philadelphia Photographer circulated internationally, and they frequently republished articles from foreign journals in translation (usually without permission, to the annoyance of some editors).4 Some journals also featured regular columns by photographers working abroad to keep their readers abreast of developments overseas. For example, Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, the founder of Photographische Mitteilungen and later teacher of Alfred Stieglitz, had a long running column in The Philadelphia Photographer in which he reported on photographic developments in Germany and Europe more broadly.5 This connection likely accounts for the exchange of prints such as Portraitstudie between the two journals.

The photographs tipped into these journals, as with Portaitstudie, were of equal importance to the texts in terms of the international exchange of photographic knowledge. Expensive to produce and laborious to insert, because an efficient method for directly reproducing photographs in texts had yet to be perfected, photographic prints were nonetheless included in these journals because readers regarded them as indispensable physical evidence of the quality of a proposed technical or artistic innovation. They allowed readers to judge the work of colleagues with their own eyes instead of trusting secondhand written commentary. These prints therefore deserve our special attention, because nineteenth-century photographers regarded them as models to follow and as starting points for further experimentation.

Portraitstudie was selected for publication in Photographische Mitteilungen not only for its fine aesthetic qualities, but also because it showcased a variation on the collotype process, an early photomechanical print process. These processes were of great interest to inventors, photographers, and publishers throughout the second half of the nineteenth century because they sought to make the reproduction of photographs in books and periodicals more efficient and economical. The collotype process became one of the most successful and widely used of these processes. In broad strokes, the collotype process is very similar to lithography, except that a glass plate is used in place of a lithographic stone. The resulting prints, as illustrated by Portraitstudie, approximated in ink the sharpness and tonal range of actual photographic prints.6 Obernetter was not the originator of this process, although he did make improvements to it, and the commenter at the Photographische Mitteilungen praised the results, particularly the deep black tones his variation on the process achieved.7

Interest in Obernetter’s process soon spread across the Atlantic, and The Philadelphia Photographer published its version of Portraitstudie eight months later. The editor at The Philadelphia Photographer, the indefatigable Edward L. Wilson, was impressed by Obernetter’s process and cheered it as evidence of the rapid improvement in photomechanical printing. As he writes in the text accompanying the image:

A good photographic magazine should, we think, serve as a record of the progress of photography as well as advocate its advancement. For this reason we serve our readers this month with another example of photo-mechanical printing. In no one branch of our art has so much effort been made, as in that of printing by mechanical means, pictures (which have all the charms of photographs). . . . Our picture this month is the result of one of the procedures alluded to, and is, we think, a very fair approach to a good plain paper print in every particular. It was printed for us in Munich, by Mr. Joseph [sic] Obernetter. The process is kindred to the Albertype process, which is so fully describe by Prof. Towler . . . and published in our last number.8

This passage points to the significance of international exchange in photographic innovation during the nineteenth century. As the editor notes in the very first lines, this print was included not only to “record the progress of photography” but also to “advocate its advancement.” The print is both evidence of Obernetter’s process and an inducement to readers in the United States to pursue their own experiments in photomechanical printing. The passage also references another variation on the collotype process, the Albertype process, developed by Joseph Albert, a Munich-based inventor and, significantly, the mentor of Obernetter. As noted above, the Albertype process was made known to US audiences through an article written for The Philadelphia Photographer by Professor John Towler, an Englishman living and teaching in the United States.9 In this one short passage, we see how the movement of prints, chemical recipes, and people of the United States and Europe together facilitated interest and improvements in the field of photomechanical printing.

Obernetter’s variation on the collotype process soon flourished in the United States. One of its main proponents was photographer and printer Edward Bierstadt, brother of famed American landscape painter Albert Bierstadt, who purchased a license to use the process in the United States.10 The process was known in this country as the Artotype and was employed in reproducing millions of photographs, many for inclusion in books and periodicals.11

United States photographers were not only on the receiving end of photographic developments in Europe, as the example of Portraitstudie might suggest, for they frequently sent prints and information about their corresponding processes to Europe and elsewhere through these specialized journals. An excellent example of this also comes from the history of photomechanical printing. About a decade after Portraitstudie was published, the US inventor Frederick Ives showcased prints produced using his screen halftone process, first in The Philadelphia Photographer (fig. 4) in June 1881 and then in Photographische Mitteilungen (fig. 5) nine months later. Ives’s photomechanical print process was revolutionary. It lacked the high aesthetic values of the collotype process, although it was cheaper and faster. With tweaking by Ives and others, the halftone process made it possible for photographic images to be reproduced regularly in newspapers and other mass media. Beyond showing that important ideas flowed from the United States to Europe and not just the other way around, I bring up this example because Ives’s work realizes the promise that The Philadelphia Photographer made a decade earlier when it stated that its mission was to “serve as a record of the progress of photography as well as advocate its advancement.” The textual and material exchanges enabled by these journals spurred photographers and inventors of his generation to pursue innovations in photomechanical printing, although it is unclear whether Ives had read them.Now that I have traced the movements and reception of Portraitstudie, I want to step back to discuss how this pair of prints points to new models for writing histories of early photography. As noted at the outset, the two main features of conventional histories of the medium that Portraitstudie disrupts are their framing in national terms and their tendency to prioritize firsts in histories of photographic inventions. With regard to the former, the two versions of Portraitstudie make clear that photographic technologies developed across national lines rather than strictly within them. Aesthetic innovations also emerged through international exchanges, although that is not addressed here. To accurately describe the early history of the medium, researchers must therefore attend more closely to the channels through which photographic knowledge was transmitted.12

The illustrated photography journals discussed here are excellent sources for conducting research into photographic networks, for they not only feature images and texts produced by international contributors, but they also traveled great distances to reach photographers often working thousands of miles apart. Tracing the movements of these journals and the prints within them, however, is no easy task given the great number of these publications that circulated during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To facilitate research in this area, I am working with colleagues at the Library of Congress and the Lens Media Lab at Yale University to build a database of prints featured in early photographic literature. Called the Reference Database to Tipped-in Photographic Samples (TIPS), it currently documents nearly fifteen hundred photographic prints from more than three hundred volumes in the holdings of the Library of Congress. Currently, we are working to expand the database to include tipped-in prints from other collections and to make the database more widely accessible by migrating it to an online platform. We hope that TIPS will encourage further research into these important outlets through which photographic knowledge was exchanged and refined during the formative years of the medium.

The example of Portraitstudie also suggests the importance of conducting broader research on the development of photographic inventions, for most important innovations (photographic and otherwise) are significantly improved upon over time by a series of practitioners that history largely forgets. The obsession with firsts in the history of photography has been usefully assessed in the recent volume Photography and its Origins, edited by Tanya Sheehan and Andrés Mario Zervigón, and I want to briefly build on that work. The idea for the collotype process, for example, was first developed in about 1855 by Frenchman Alphonse-Louis Poitevin and drew on the workings of lithography; however, German inventors such as Joseph Albert and Obernetter, among others, made significant improvements to the process in the 1860s and 1870s that made it viable as a commercial printing process.13 Other photographers and scientists continued to fine-tune the process in the following decades to keep pace with advances in printing technologies. Instead of focusing narrowly on firsts, tracing how photographic and photomechanical technologies were incrementally elaborated upon over time can allow for a more collaborative and international history of early photography than is often understood, as suggested by this very brief history of the collotype. The example of the collotype also suggests the need for great attention to photography’s intermedial history, to the connections between photographic and traditional print processes, such as lithography, that are often lost in histories of photography.

By outlining the movements of Portraitstudie from Berlin to Philadelphia and my own journey of researching this pair of prints, I hope to offer new paths forward for the study of early photography in the United States and Europe. This is merely one case study among many that points to the productivity of pursuing histories of photography beyond the confines of national borders and considering the impact of international exchange and collective experimentation in the advancement of the medium.

Cite this article: Katherine Mintie, “A Portrait on the Move: Photography Literature and Transatlantic Exchanges in the Nineteenth Century,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9729.

PDF: Mintie, Portrait on the Move

Notes

This article began as a paper for the Object Biographies panel organized by Margaretta Lovell for the College Art Association Annual Conference in 2019. The author wishes to acknowledge Margaretta Lovell, her fellow presenters, and members of the Berkeley Americanist Group for their feedback on her paper. Emily C. Burns and Erin Pauwels also offered many insightful comments and editorial suggestions. Finally, I wish to thank Adrienne Lundgren for her continued support on this project and Paul Messier at the Lens Media Lab for sharing his database expertise.

- Concerns over the incompatibility of photography and the printing press emerged not long after the invention of photography. William Henry Fox Talbot, an inventor of paper photography, spent much of his later career working on an early form of photogravure. See Larry J. Schaaf, “‘The Caxton of Photography’: Talbot’s Etchings of Light” in William Henry Fox Talbot Beyond Photography, eds. Mirjam Brusius, Katrina Dean, and Chitra Ramalimgam (New Haven, CT: Yale Center for British Art, 2013), 161–89. ↵

- As the writer for Photographische Mitteilungen stated, the studio was furnished with Renaissance Revival furniture that showed an “assiduous attention to the correct style.” “Unsere artistische Beilage,” Photographische Mitteilungen 8 (July 1871): 236. Many thanks to Sasha Rossman for his assistance in translating the German passages. ↵

- This especially true of US technical histories of photography, starting with Robert Taft’s landmark Photography and the American Scene, A Social History, 1839–1889 (New York: Macmillan, 1938). See François Brunet, “‘An American Sun Shines Brighter;’ or, Photography Was (Not) Invented in the United States,” in Photography and its Origins, eds. Tanya Sheehan and Andrés Mario Zervigón (London: Routledge, 2015), 131–44. As Brunet notes, the tendency to frame histories of photography in national terms is less pronounced in art-historical accounts of the medium since Beaumont Newhall’s The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1937). Emerging histories of photography (for instance in Eastern Europe and Africa) are frequently nationally defined as a result of neglect in prior histories of photography. On this phenomenon, see Geoffrey Batchen, review of Photography and Egypt by Maria Golia and Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java by Karen Strassler, The Art Bulletin 93 (December. 2011): 497–501. The national focus of American histories of photography will be critically assessed in the Fall 2020 special issue of Panorama on “Re-Reading American Photographs” with guest editors Monica Bravo and Emily Voelker. ↵

- The United States did not have international copyright agreements until the late nineteenth century, so the reprinting of articles (and often entire books) from abroad was a common feature of United States print culture during the nineteenth century. On this phenomenon, see Meredith L. McGill, American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting, 1834–1854 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007). ↵

- United States–based correspondents also sent photographic news to Europe. Some of the most lively missives come from Coleman Sellers II, a Philadelphia-based engineer and amateur photographer (also grandson of painter Charles Willson Peale), who wrote a column for The British Journal of Photography between 1861 and 1864. ↵

- For more information on the collotype process, see Dusan C. Stulik and Art Kaplan, “Collotype,” in The Atlas of Analytical Signature of Photographic Processes (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2013). Accessed October 7, 2019, https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/atlas_collotype.pdf ↵

- “Unsere artistische Beilage,” 235–36. ↵

- “Our Picture.” The Philadelphia Photographer 9 (July 1872): 270. ↵

- “Our Picture,” 270. ↵

- Edward Bierstadt bought licenses to several European patents for producing collotypes, including those owned by Obernetter and Albert. See “The Studios of America: No. 6 Bierstadt’s Artotype Atelier, New York,” The Photographic Times and American Photographer 13 (May 1883): 195–98. ↵

- As noted in “The Studios of America: No. 6 Bierstadt’s Artotype Atelier, New York,” the main applications of the Artotype process were “illustration for illustrated catalogues connected with mercantile art and manufacture” and “portraiture . . . executed for book illustration.” In terms of the scale of the operation, the writer goes on to describe an order being filled for “a hundred and twenty thousand” copies of a given print. “The Studios of America,” 196. ↵

- There have been numerous recent monographs, edited volumes, and articles devoted to the art and architecture of the Atlantic world. See, for example, George W. Boudreau and Margaretta M. Lovell, eds., A Material World: Culture, Society, and the Life of Things in Early Anglo-America (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019); Emily C. Burns, Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018); Jennifer Van Horn, The Power of Objects in Eighteenth-Century British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Daniel Maudlin and Bernard L. Herman, eds., Building the British Atlantic World: Spaces, Places, and Material Culture, 1600–1850 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016); and Jennifer L. Roberts, Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014). ↵

- See Stulik and Kaplan, “Collotype.” ↵

About the Author(s): Katherine Mintie is the John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Curatorial Fellow in Photography at Harvard Art Museums