Do US House Special Elections Foreshadow Partisan Waves?

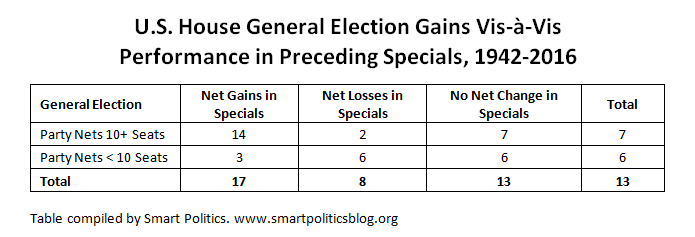

Since 1942, parties that gained at least 10 U.S. House seats in a general election were seven times more likely to have netted seats than lost seats in that cycle’s preceding specials

Rallying behind Jon Ossoff (pictured), a filmmaker and ex-congressional staffer, the 6th CD race has alternately been viewed as a focal point for nationwide Democratic anger against Donald Trump (and last November’s election results) and a beacon of light for the party – hoping that a victory in the GOP-leaning district would portend a Democratic wave in November 2018.

That translated into millions of dollars into Ossoff’s campaign coffers and Donald Trump weighing in on the race at the 11th hour to criticize the now high-profile Democratic candidate.

However, Ossoff failed to win an outright majority of the vote (48.1 percent) and will now face second-place finisher Karen Handel (19.8 percent) in a June 20th runoff that is expected to be closely decided – assuming Democrats do not lose interest and momentum in the district after Tuesday’s setback.

So just how wise is it for Democrats to have invested so heavily in this special election, pitching it as a sign of their 2018 prospects to make big gains in the chamber?

Are specials a reliable national litmus test of what is to come in the subsequent general election?

The evidence is mixed but, collectively, there appears to be a correlation.

Smart Politics examined the 378 special U.S. House elections conducted across the previous 38 election cycles since 1941 and found that the party netting more seats via specials was twice as likely to make gains in the subsequent general election.

Moreover, during the 23 cycles in which a major party netted at least 10 U.S. House seats, that party was seven times more likely to have netted seats in special elections (14 cycles) than lost seats (just two cycles).

Since 1942, major parties have netted at least 10 U.S. House seats in 23 of the 38 general elections.

Of these 23 cycles with notable gains, 14 had already seen that party make net gains via special elections earlier that cycle.

In recent decades, there has been selective evidence of partisan waves being preceded by multiple special election pick-ups.

For example, five of the six seats that were flipped in specials during the 93rd Congress prior to the 1974 midterms were won by Democrats: in Pennsylvania’s 12th CD (John Murtha), Michigan’s 5th (Richard Vander Veen) and 8th (Bob Traxler), Ohio’s 1st (Thomas Luken), and California’s 6th (John Burton).

Democrats went on to net 49 seats in November 1974.

Twenty years later, Republicans won both pick-ups that occurred in special elections during the 103rd Congress: in Oklahoma’s 6th CD (Frank Lucas) and Kentucky’s 2nd CD (Ron Lewis) – both contests held in May 1994.

Democrats had held Kentucky’s 2nd CD seat – vacated after the death of 21-term Rep. William Natcher – for over a century and the GOP had not fielded a candidate in the race in seven cycles against him.

The GOP netted 54 seats in the 1994 midterms.

In 2008, prior to the Democrats netting 21 seats with Barack Obama at the top of the ticket, the party flipped three seats: Illinois’ 14th CD (Bill Foster), Louisiana’s 6th CD (Don Cazayoux), and Mississippi’s 1st CD (Travis Childers).

The GOP, behind Roger Wicker, had won the MS-01 race by 47 points in 2002 and 32 points in 2006 (with the Democrats failing to field a candidate in 2004). Republicans carried IL-14 behind Speaker Denny Hastert by 49 points in 2002, 37 points in 2004, and 19 points in 2006. Democrats had not fielded a candidate against Richard Baker in LA-06 in 2002 or 2006 and lost by 53 points in 2004.

However, netting special election pick-ups prior to the general election has not been a necessary condition en route to a medium- to large-sized partisan wave.

There have been seven cycles since 1942 during which neither party gained a partisan advantage from the preceding specials that were held – and yet one of the parties gained a large number of seats in the general election all the same.

For example, neither Democrats nor the GOP picked off any seats in specials before the general election in 1947-1948 (when Democrats gained 75 seats), 1957-1958 (Democrats +49 seats), 1971-1972 (GOP +13 seats), 2005-2006 (Democrats +31 seats), and 2013-2014 (GOP +13 seats).

Each party flipped one seat in specials conducted from 1965-1966 (with Republicans gaining 47 seats) and 2009-2010 (GOP +63 seats).

Moreover, there have been two wave elections since 1942 during which the party that made big gains in the general election actually lost seats during that cycle’s preceding specials.

In November 1944, Democrats gained 20 U.S. House seats with Franklin Roosevelt winning a fourth term at the top of the ticket.

Democrats picked up one House seat before the general election – with California’s Clair Engle winning the seat vacated by Republican Harry Englebright in August 1943.

However, from November 1943 through mid-June 1944 Republicans flipped four others:

- Kentucky’s 4th CD (November 30, 1943): Chester Carrier (seat vacated by Democrat Edward Creal)

- Pennsylvania’s 2nd CD (January 18, 1944): Joseph Pratt (James McGranery)

- Colorado’s 1st CD (March 7, 1944): Dean Gillespie (Lawrence Lewis)

- New York’s 11th CD (June 6, 1944): Ellsworth Buck (James O’Leary)

Twenty years later, in 1964, a Democratic wave with Lyndon Johnson at the top of the ticket netted the party 37 seats in the general election.

Prior to that November, the only two seats that flipped were both Democratic-held seats to the GOP: California’s 1st CD (won by Don Clausen after the death of Clement Miller) and California’s 23rd CD (won by Del Clawson after the passing of Clyde Doyle).

Both of these specials, of course, were conducted before the assassination of John Kennedy in November 1963.

However, the lone special election for a seat vacated by a Republican conducted thereafter was nonetheless held by the GOP (in Tennessee’s 2nd CD with Irene Baker filling the vacancy after the death of her husband Howard Baker, Sr.).

After also including cycles during which small partisan shifts occurred in the general election (less than 10 seats), the party that made gains in the general election had flipped the most seats in the preceding specials 17 times but lost more specials eight times. [In the remaining 13 cycles, neither party had a net advantage in seats flipped in special elections].

It should be noted that specials comprise a relatively small percentage of elections to the chamber (2.2 percent of the nearly 17,000 U.S. House elections conducted since 1941) and at times the results of a given race for which may be more reflective of the specific political conditions of the district than any potential national wave that is afoot.

Therefore, as a rule it is risky to suggest the results of any one special is predictive of shifting national partisan winds but, an examination of all specials conducted in a cycle as a whole can be generally suggestive of what is to come.

Follow Smart Politics on Twitter.