Playing the Race Card: Thomas Le Clear’s High, Jack, Game

As a candidate for the Americanist faculty position at Colby College, I was among the first people to get a tour of the Lunder Collection installed at the Colby College Museum of Art in the spring of 2013. Curator Lauren Lessing was charged with taking me through the new galleries, to test and to tantalize. From paintings by the leading American Impressionists to the early modernists of the Taos Society, the collection was impressive, even overwhelming. But one small genre painting stopped me in my tracks (fig. 1).

I then knew neither the artist nor the title of the work—wall labels had yet to be hung—but I was struck by two things that did not quite add up. The painting featured a youthful African American man with uncaricatured features. Yet, from my research on visual humor, I immediately recognized that the instruments of his labor—brushes and a bucket of whitewash, used to brighten the walls of soot-filled homes—were often the stuff of racial satire and caricature in the nineteenth century. Was this a sympathetic portrayal of an African American or something much more complicated? My gut said we were dealing with the latter, so I shared this with Lauren.

She, in turn, shared with me what the museum knew about the recently acquired painting. Sitting on a city street, two boys are dealt into a card game known as Seven Up, All Fours, or Old Sledge. The New York Tribune tucked under one arm indicates they are newsboys, while their ruddy complexions and hair color—one reddish, the other deep brown—signify Irishness. Surrounding them are several objects associated with gambling, including a shiny penny and a knucklebone, which serves as the basis for modern-day jacks. The mismatched clothes of the black man at right—Lauren pointed to the Union Army jacket and US Marine Corp cap—present him as contraband, an escaped slave who sought “protection” and employment from Union forces during the Civil War. He has put aside his whitewashing tools to witness the game, and he has a position with a privileged view of both hands of cards. The upturned card on the pavement signals that hearts are the trump suit. Admitting to playing Seven Up to help make sense of the game’s intricate rules, Lauren noted that the ace of hearts is in play, and the newsboy toting the Tribune can only follow with the jack of hearts.1 With aces high, his challenger will win this trick, calling out the phrase “High, Jack.” But will he win the game, I wondered? Only the African American man, with his bird’s-eye view of the scene, knows for sure. Meanwhile, in the viewing position of the red-haired boy, we pin our hopes on the ace of spades—the high-scoring card that could turn the tables.

Once I joined the faculty at Colby College, I was eager to learn more about Thomas Le Clear’s High, Jack, Game, so much so that I made it the subject of a public talk at the museum in November 2013. My first move was to situate the painting within Le Clear’s oeuvre. Scant secondary sources on the artist, together with exhibition and museum records, taught me that he spent much of his career in New York, painting portraits and genre scenes. Among the works he exhibited at the National Academy of Design, where he became a full academician, are an earlier, unlocated version of High, Jack, Game from 1861 and a celebrated genre scene, Young America of 1863 (fig. 2).2

In Young America, there is another pair of Irish newsboys in the lower left, playing a game of jacks, with a Buffalo newspaper beside them. At center is a dry goods box—the same object on which the African American man sits in High, Jack, Game. On this box a white boy announces a meeting of the Young America movement, a faction of the New York Democrats. Le Clear places a black man at the margins of the scene, emerging from behind the wall where the meeting notice is posted and looking intently at the back of the speaker. This detail suggested to me that the man’s political and social status was a matter of public discourse, but not a matter in which he had full participation or control. The agent in the scene is the white, male youth, while the African American is the humble, passive recipient of his declaration. It was never far from my mind that Young America was painted the same year that Abraham Lincoln put into effect the Emancipation Proclamation.

Reading High, Jack, Game alongside Young America helped bring into focus the period politics of Colby’s painting. Both artworks refer to tensions between Irish immigrants and African Americans, as they competed for jobs in northern cities and for visibility in the war. But High, Jack, Game features greater interaction between these groups and places it squarely before the viewer. Le Clear’s compositional choices, moreover, point to a possible shift in agency, as the black subject in the Colby picture occupies the highest position and opens his mouth to speak, as if coaching the boys on their next move. This was a detail previously overlooked, as the African American was described at the artwork’s most recent sale as “not participat[ing] in the card game, . . . perhaps uninvited or unwilling to play.”3 Digging into the history of Seven Up, however, showed why Le Clear might have placed an African American in the role of instructor; this was a game traditionally played by slaves on southern plantations. The Irish boys, then, take up the “black” game, just as the African American takes up the “white” role of the Union soldier, his ties to the nation highlighted by his red scarf, white collar, and blue-tinged coat. On the face of it, the black man appears to be in a powerful position, one that differs significantly from the passive or marginal role generally played by African Americans in antebellum and Civil War genre paintings, including Farmers Nooning (1836; Long Island Museum, Stony Brook) by William Sidney Mount (1807–1868), The Card Players (1846; Detroit Institute of Arts) by Richard Caton Woodville (1825–1855), and Le Clear’s Young America.

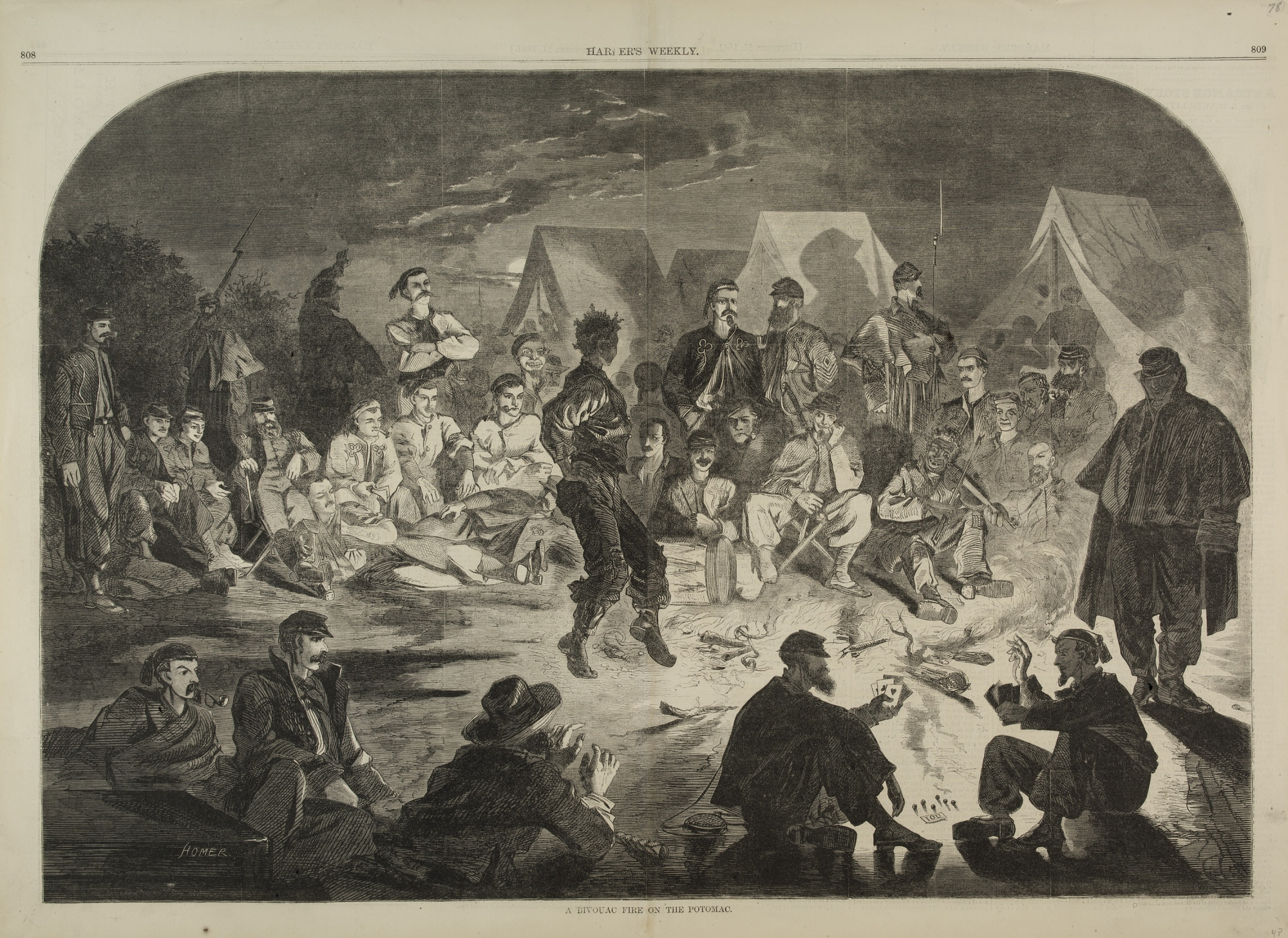

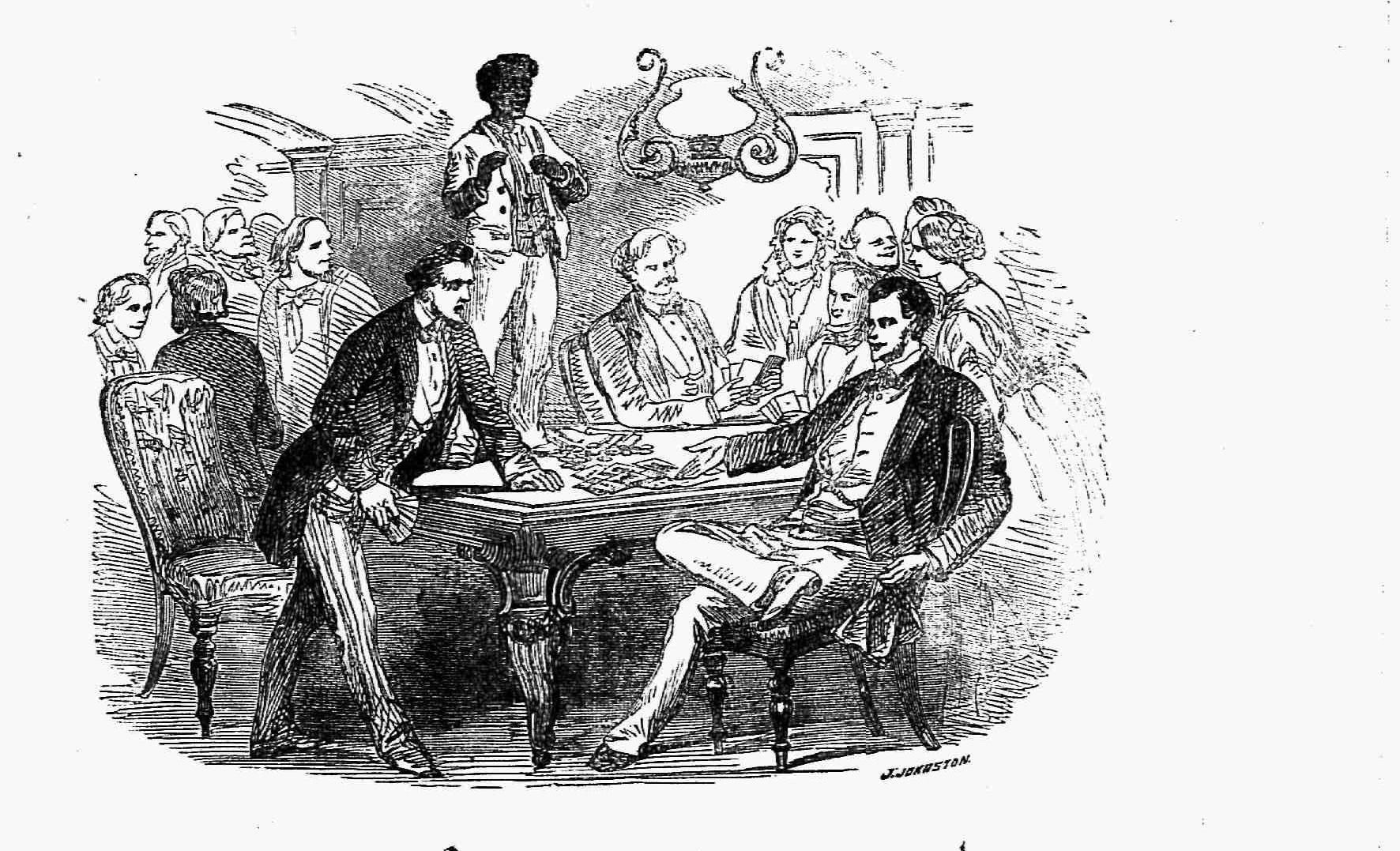

This exchange of positions, however, seemed to me neither complete nor successful; the man’s uniform is woefully mismatched, and the boys look unsure of the rules of play for Seven Up. What is more, the black man’s familiarity with the game may actually call into question his agency. Writing a book on racial humor,4 I encountered plenty of stereotypical depictions of African American card players in print and photographic media, many portraying their subjects as gamblers more interested in deceit than honorable work. Gambling was seen as especially transgressive for blacks in antebellum society because it implied they had property to lose, when chattel slavery denied them that right.5 For this reason, they could be represented as not only players but also bets—the objects won or lost in a white man’s wager. Such scenarios were metaphors for the Civil War itself, in which blacks became pawns in a competition for political and economic power. This was how Peter Wood read the 1861 print by Winslow Homer (1836–1910), A Bivouac Fire on the Potomac (fig. 3), which features Union soldiers playing a high-stakes card game directly beneath a grinning black fiddler.6 That whites gambled with the lives of slaves was an idea that black abolitionist William Wells Brown also famously explored in the novel he first published in the United States as Clotelle: A Tale of the Southern States (1864). Its frontispiece depicts a white slave owner who, having gambled away his money, bets his “fine-looking, bright-eyed mulatto boy,” seen standing on the card table (fig. 4). As in High, Jack, Game, white men in the world of Clotelle hold all the cards.

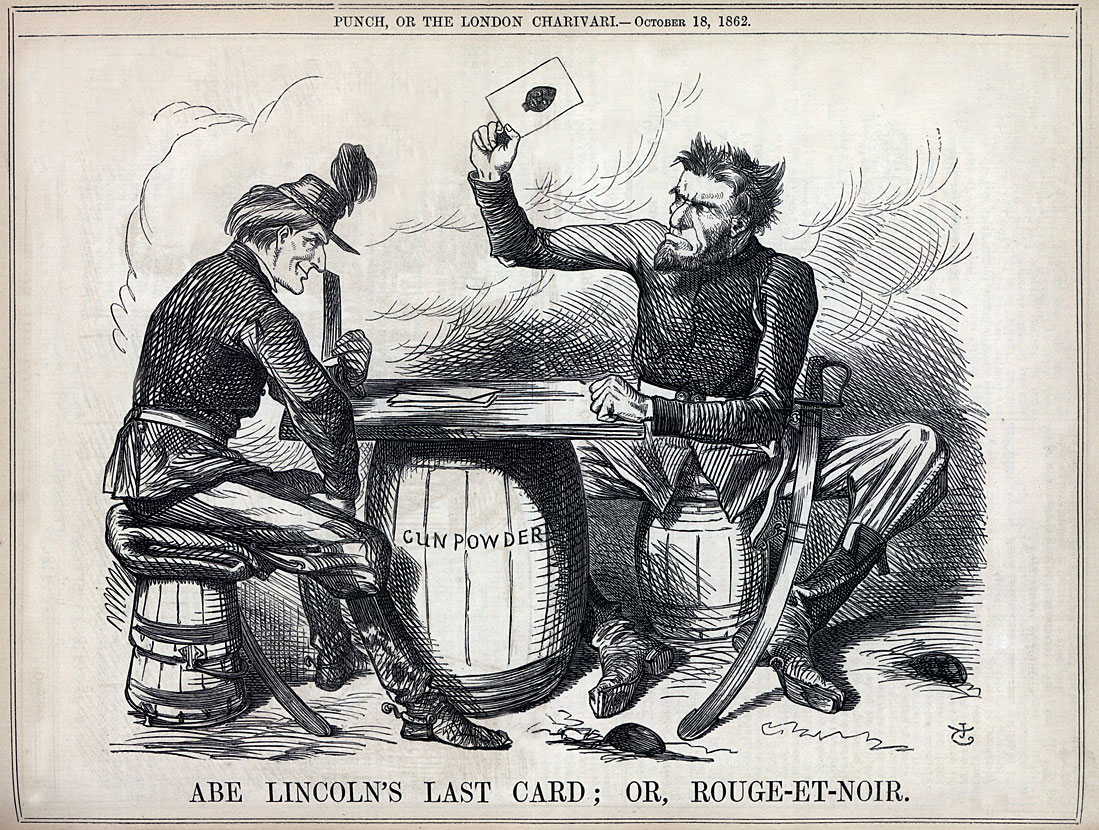

Homer’s engraving and Brown’s frontispiece are just two examples of popular print culture that I have placed into conversation with Le Clear’s painting. My most important discovery, when it comes to understanding the connotations of card playing in High, Jack, Game, is a satire by John Tenniel published in the London humor magazine Punch in October 1862 (fig. 5). Abe Lincoln’s Last Card; or, Rouge-et-Noir interpreted the Emancipation Proclamation—issued in preliminary form the previous month—as the action of a devilish gambler competing with the Confederacy. Tenniel’s print accompanied a poem ventriloquizing Lincoln. Consider this excerpt:

BRAG’s our game: and awful losers

We’ve been on the Red.

Under and above the table,

Awfully we’ve bled.

Ne’er a stake have we adventured,

But we have lost it still,

From Bull’s Run and mad Manassas,

Down to Sharpsburg Hill.

When luck’s desperate, desperate venture

Still may bring it back:

So I’ll chance it—neck or nothing—

Here I lead THE BLACK!

If I win, the South must pay for’t,

Pay in fire and gore:

If I lose, I’m ne’er a dollar

Worse off than before.

From the Slaves of Southern rebels

Thus I strike the chain:

But the slaves of loyal owners

Still shall slaves remain.7

To solidify the connections between image, text, and context, Tenniel rendered the spade on Lincoln’s trump card in the shape of a caricatured black face.

Lincoln himself used the metaphor of the “last card” when speaking about emancipation and his need to save the nation, declaring in July 1862 that “I shall not surrender this game leaving any available card unplayed.” He was replying to a letter from Maryland statesman Reverdy Johnson, whom the president had dispatched to New Orleans to investigate complaints about the Union occupation of the city. As Johnson explained to Lincoln, the Louisiana people were uncomfortable with enlisting black soldiers in the Union army.8

This period discourse allowed me to see the play underway in High, Jack, Game in a new light. Remember that the ace of spades (what Punch dubbed “THE BLACK”) has not been played, a powerful card pointed toward the African American man in the cobbled-together uniform, signaling to viewers that black men were joining the war effort. Perhaps Le Clear’s figure looks to the cards in the boys’ hands because his freedom, and the future of the nation, depend on who wins. The black man may be able to coach the players, but it is ultimately their trick to master. It is up to the red-haired newsboy to lead the black.

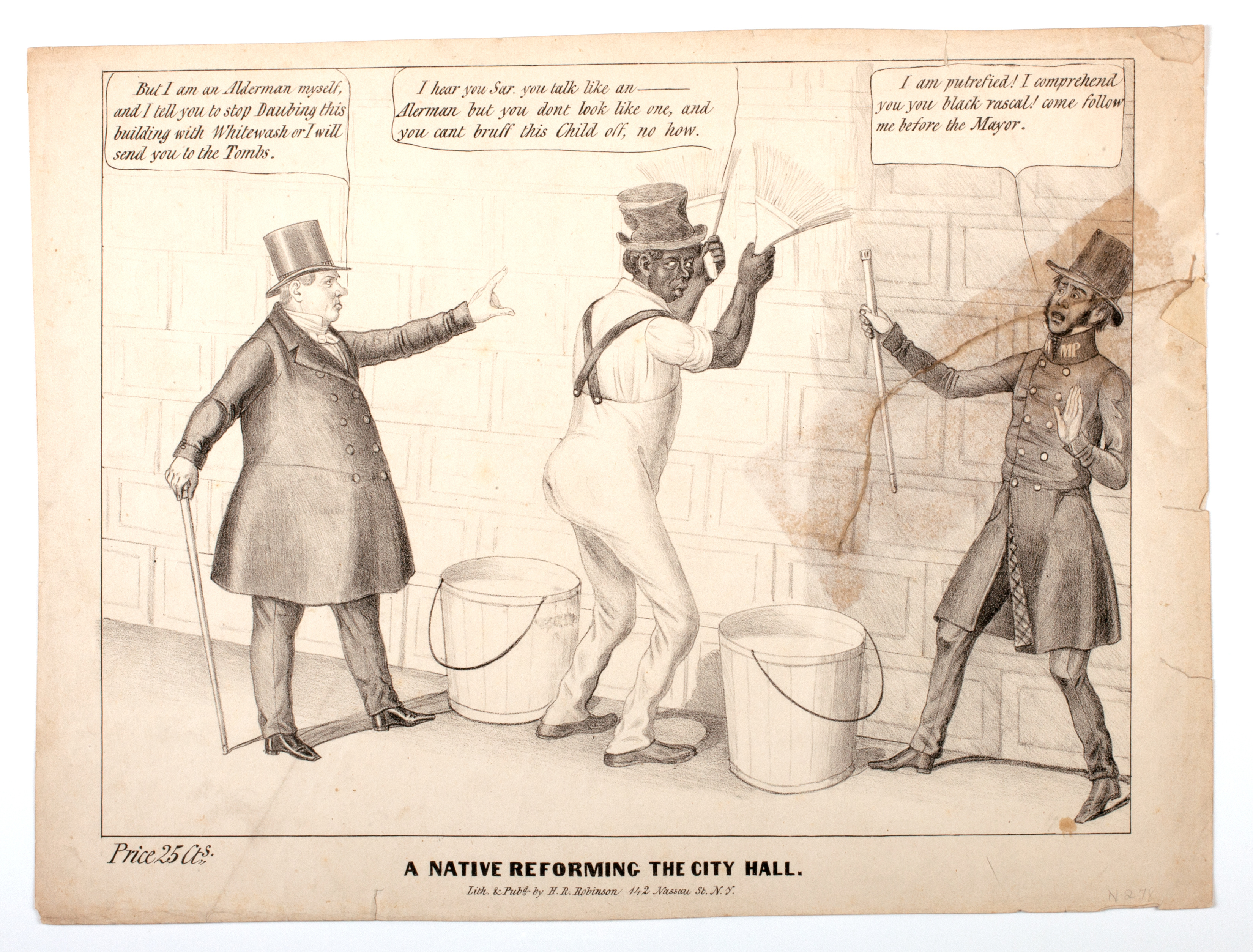

I could, of course, not forget about the detail that first captured my attention: Le Clear’s portrayal of the black figure as a whitewasher. As Sarah Burns explains in Painting the Dark Side, citing examples from the Civil War, the racial humor associated with whitewashing “hinged on the idea of whitewash as a veneer, a cover-up, a deception, a mode of temporary concealment.” It articulated and assuaged white fears that African Americans could conceal their racial difference—or, that blacks would be “whitened” through emancipation.9 My research on whitewashing uncovered many political cartoons that evoked this trope, including one from 1844 that shows how this labor could be imagined as a transgressive act against white power (fig. 6). An African American man applies whitewash to the exterior of city hall, while two white aldermen threaten to take legal action if he continues his work. They are invested in maintaining the true “color” of the city government, which was being taken over by a New York political party that called itself the “Native Americans” and then the “American Republicans” in 1844.

The black contraband dressed as a Union soldier in High, Jack, Game has set down his whitewashing tools, but they are ready to be taken up again. What, exactly, might he try to obscure or whiten? Period stereotypes, after all, cast this figure as a dishonest card player. But the basket on the ledge behind the figure, which contains cloth of red and blue, holds out the possibility that his work will take up the cause of the nation. A second connotation of whitewashing in nineteenth-century America is also applicable to the scene; it could mean defeating an opponent easily by winning every point or game. In the boys’ game of Seven Up, one of them has the upper hand—the dark-haired chap who will shortly call out “High, Jack.” But the inclusion of the ace of spades in his opponent’s hand, and the black man’s unworried expression, point to a different conclusion: the game will be won easily when the newsboy at left “plays the race card.”

High, Jack, Game took me on a journey—from the artist’s biography and formal analysis of his work, to visual comparisons and discourse analysis—that I model in the Colby classroom. When I walk students through my research process with this painting, their most-asked question—How could such a small canvas mean so much?—always brings me back to the lessons about American genre painting that Elizabeth Johns taught my generation of scholars. To understand what these artworks communicated about so-called everyday life in America, you must creatively reconstruct their multilayered and intermedial messages.10 There is no straight path or single meaning; discoveries are in the detours. A second question students regularly ask me—What was in it for Le Clear?—allows us to reflect on moments when American artists may have “played the race card.” Although the Punch cartoon of Lincoln illustrates that phrase, the idiom was not popularized until the 1980s and ’90s. Retrospectively, however, we can apply the phrase to Le Clear and other mid-century genre painters, such as William Sidney Mount and Eastman Johnson, who could choose to exploit ideas about race. In High, Jack, Game, the inclusion of an uncaricatured black body may have simply conveyed to white bourgeois viewers that the artist was engaged with his intended audience and the most pressing concerns of the day. Le Clear, in other words, was dealing himself into a high-stakes game—a game we might call race in America—without challenging its rules or perhaps even fully investing in its outcome.

From the moment I encountered High, Jack, Game, I knew the Colby College Museum of Art had acquired a painting fraught with ambivalence. And that was precisely why it needed to be studied.

Cite this article: Tanya Sheehan, “Playing the Race Card: Thomas Le Clear’s High, Jack, Game,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no.2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1665.

PDF: Sheehan, Playing the Race Card

Notes

- Readers wishing to learn more about the rules of play may consult “North American All Fours, Old Sledge or Seven Up,” https://www.pagat.com/allfours/allfours.html#america, accessed August 17, 2018. ↵

- The Colby College Museum of Art dates their painting to approximately 1865 and maintains that it is not the same work exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1861, based on descriptions of the latter. I have not yet been able to disprove this claim or more precisely date the artwork in the Lunder Collection using historical records. ↵

- Christie’s auction lot essay, https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/Lot/thomas-le-clear-1818-1882-175536-details.aspx, accessed August 4, 2018. The same essay conflates the unlocated 1861 version of High, Jack, Game with the canvas in the Lunder Collection. ↵

- See Tanya Sheehan, Study in Black and White: Photography, Race, Humor (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018). ↵

- See Kenneth S. Greenberg, Honor and Slavery: Lies, Duels, Masks (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998). I am grateful to Greenberg for his email on the subject of black gambling, September 29, 2014. ↵

- Peter H. Wood, Near Andersonville: Winslow Homer’s Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 44–45. ↵

- “Lincoln’s Last Card; or, Rouge-et-Noir,” Punch, October 18, 1862, 161. ↵

- Abraham Lincoln wrote to Reverdy Johnson on July 26, 1862, “I am a patient man—always willing to forgive on the Christian terms of repentance; and also to give ample time for repentance. Still I must save this government if possible. What I cannot do, of course I will not do; but it may as well be understood, once for all, that I shall not surrender this game leaving any available card unplayed.” See The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 5, ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953, 342–44. For more card-playing metaphors by Lincoln, see James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 106. ↵

- Sarah Burns, Painting the Dark Side: Art and the Gothic Imagination in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 117–19. ↵

- See Elizabeth Johns, American Genre Painting: The Politics of Everyday Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993). ↵

About the Author(s): Tanya Sheehan is on the Art Department faculty at Colby College