Looking for What’s Not There in the Marcel Breuer Papers

What if we encourage our students to begin in the archive, to view sources within archives as places from where they can pose questions instead of just as materials supplying answers to questions already asked? What if we ask them to treat the content of an archive as revealing gaps between documents still needing to be filled and not as offering a continuity simply waiting to be read? What if we find a way to capture those occasional feelings of excitement and confusion and frustration, those moments of serendipitous discovery that yield ideas for a future research investigation or a tangential project that we would pursue on a whim if we had an extra day on a research trip? And then, what if we are mindful of the realities of what it means to be a student and a faculty member in the present, in which contemporary economics make the idea of the researcher—student, junior faculty, senior faculty, or independent scholar—spending uninterrupted hours and days in a reading room an increasing rarity? What would be the results?

As a case study: In the spring semester of 2017, I taught a graduate-level survey of Architecture and Urban History in the United States at the Pratt Institute. This hybrid lecture and seminar course covered content from the colonial period to the present. Despite being a graduate course, it presumed students had no previous knowledge of the material. Students pursuing the two-year MS degree in historic preservation often took this as a first-year foundations course, part of a broad first-year curriculum of interdisciplinary coursework combining history, theory, and practice and the second of a two-semester sequence in a global historical survey of architecture and city development. Although housed in the Historic Preservation program, the course enrolled students across the Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment. First- and second-year students in urban planning and architecture also enrolled, resulting in a class of twenty-three students.

I was given a great deal of leeway in structuring the course. Rather than a course on just great buildings, the course examined cities, from sewage systems to tower spires. The course read the development of the built environment through city and suburban planning, material innovations, and population shifts. Nineteenth-century factory towns and logging cities and twentieth-century postwar shopping malls were covered. I wanted students to adopt an expansive way of thinking about the stuff of an urban material culture, which was built into the syllabus. Discussions of readings broadened an understanding of relevant topics. Readings included Whitney A. Martinko’s positioning of circulated prints of demolished buildings as a preservation practice in Early Republic Boston; Maurie D. McInnis’s mapping of the spaces and places of the slave exchange in Richmond and New Orleans; Daniel Bluestone’s examination of public life as guiding the attempted preservation and ultimate demolition of the Chicago Mecca apartment building; and Kate Brown’s comparative analysis of the frontier developments of Billings, Montana, and Karaganda, Kazakhstan.1 Introducing Martinko’s article early, while chronologically appropriate, set up what the objects and dynamic social worlds of preservation research could be. Her article inspired a conversation about whether or not her examples could and should be counted as materials of historic preservation. By rigorously thinking about sources, materials, and approaches from the start, students were primed to carry this kind of inquiry into their own investigations.

The freedom to design this course extended to the course assignments. It is worth mentioning that I considered an assignment introducing primary sources and historical research from the position of a contingent faculty member, balancing wanting to support program-mandated student learning objectives against wanting to support innovative projects without guarantees of long-term departmental or institutional support. Instead of offering the kinds of exams that punctuated the first half of the two-course sequence, the program director and I discussed how this course could position students to start thinking about their thesis projects, to be realized the following year. As several students did not come to the program directly from their undergraduate education and had several years away from researching and writing papers, and as the undergraduate programs of many in the course did not include sustained research investigations as part of their program expectations, I built a semester-long research assignment into this course. I wanted students to ask questions about what fell within the purview of the field of historic preservation, to grapple with the fact that primary source materials are often partial, and to recognize that, rather than marking an inviolable roadblock in their research, such partiality offers an opening to pose new questions of the historical record, the works referenced and implicated in this record, and the built environment in general.

In many ways, the assignment was a traditional scaffolded research paper. Across the semester, students wrote a project abstract, prepared an annotated bibliography, delivered a fifteen-minute presentation, and then completed a final paper, which they were informed at the beginning of the semester could serve as the start of a larger project. Prior to writing the abstract, students gave a short presentation, no longer than three minutes, on a document they found in the Archives of American Art’s Marcel Breuer papers.2 They introduced and briefly contextualized the content of their document—a letter, a building plan, a contract, a photograph—and then addressed what questions the document raised for them—big or small, obvious or nebulous in their connection—and in what direction or directions they saw their investigation of the material going. After each presentation, time was given for the rest of the class to provide feedback and pose their own questions of their classmates’ documents.

I encouraged the class to use what was there in the document to locate what was not in the document, and, more broadly, to use what was there in the archive to locate what was not in the archive. Although Breuer was heavily present in his own papers, students did not have to focus on Breuer himself or his work as the central topic for their research. After selecting and interrogating an initial document, there was no obligation to stay within the world of Breuer. The Breuer papers could certainly serve as a greater resource for Breuer’s practice if students wanted to work directly on an aspect of his practice and therefore needed this resource for their projects. Students were, however, encouraged to go beyond the historical, geographic, and biographic domain of Breuer. We discussed before and after the first presentation how research projects were expected to evolve from the selected document, however narrowly or broadly the student saw fit. The archive was a beginning: a place to spark new discoveries, pose questions, and shake loose ideas.

I decided to have students mine the Breuer papers for several reasons. First, this collection provided some structure to the somewhat amorphous and intimidating directive to “write a paper on something related to this course,” a familiar prompt that many of us have received during our own coursework and perhaps occasionally given to advanced undergraduate and graduate students. Second, despite the course not requiring prior knowledge of the field, the status of Breuer anticipated some name recognition for most of the students. Breuer also held some local currency for students studying preservation and the reuse of buildings, given the then-recent press coverage of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s renovation and start of programming in the Upper East Side Breuer building, previously commissioned and occupied by the Whitney Museum of American Art.

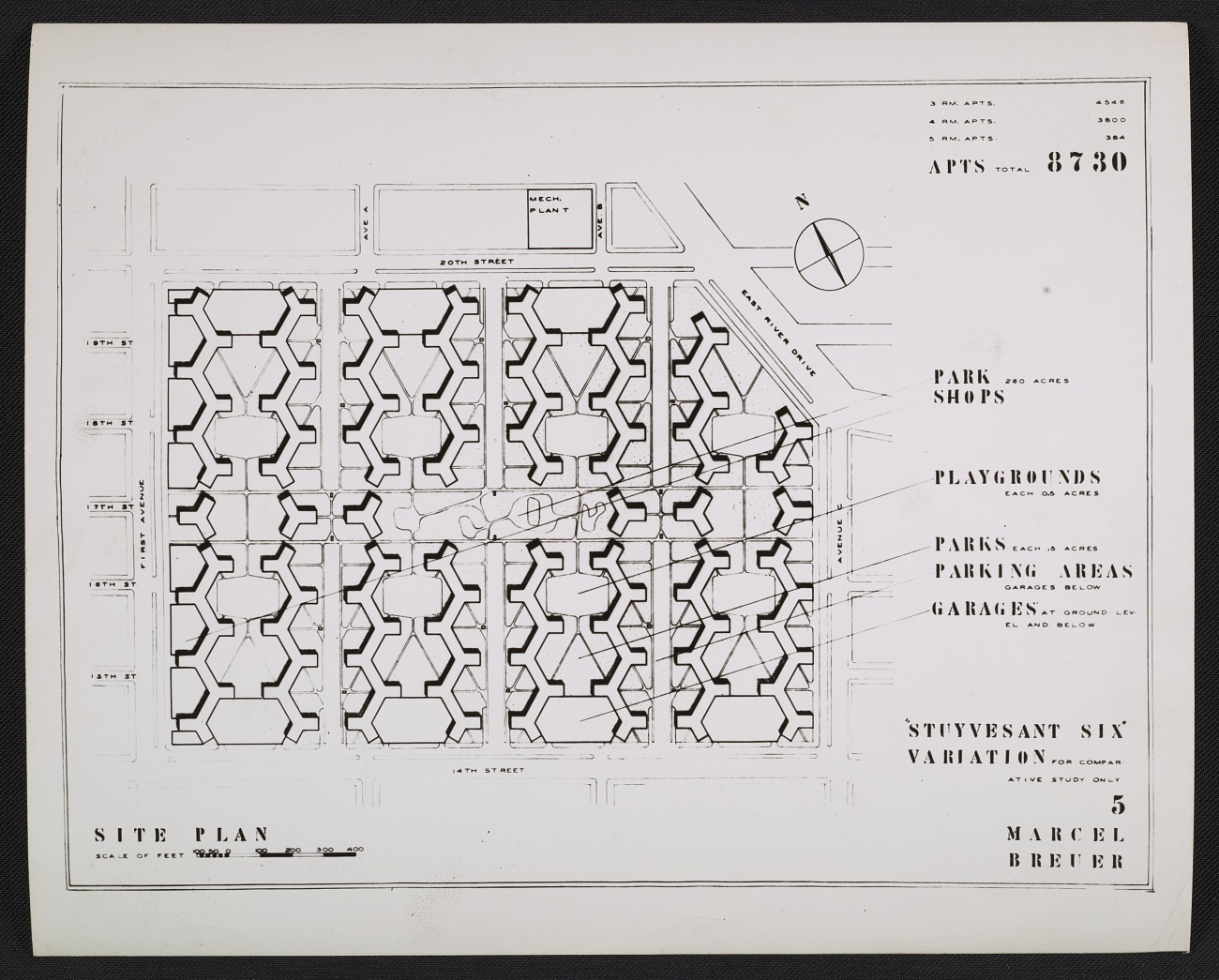

This local familiarity was borne out in some of the documents selected. Students gravitated to the Breuer Project Files. Several landed upon various documents related to his proposal for Stuyvesant Six, an alternative to Metropolitan Life’s Stuyvesant Town development.3 Research projects that sprung from these documents included comparative studies with other Metropolitan Life developments and with more recently built projects overseen by the New York City Housing Authority. Students also pursued analyses of the policing of housing developments, the relationship between physical structures and social dynamics in urban prisons, and the maintenance and accessibility of shared residential greenspaces. These projects led students to consult additional materials such as census data, interviews, planning documents, and community board minutes, many of which were hosted in online repositories. Name recognition led other students to the Whitney Museum Project Files, specifically the letter of agreement between Breuer and Lloyd Goodrich.4 It is worth noting that some of the students who started with material related to the Whitney commission had the greatest difficulty developing their projects, perhaps in part because of the stifling effect of a certain kind of familiarity. It prevented them from identifying what they did not know about the project or what questions their documents provoked beyond the museum commission itself.

More successful, although not without occasional research frustrations, were students who seemed to embrace the idea of not knowing from the start, willing to search for what was not obviously in the archive. One student entered into a project focused on the interwar collapsing of domestic and corporate work environments through Breuer’s design notes for the Cesca chair. Another used correspondence inviting Breuer to consult on international urban developments to question the subtle encoding of exported American design vocabularies in postwar United States embassy buildings. Yet another looked at a world that has receded into the background of preservation despite being clearly in the foreground of architecture and design history, as in one undated and unlabeled photograph of a gathering of professionals at an international exhibition in which the central figure holds a lit cigarette.5 This student looked into the history of smoking culture, which led her to ask why smoking rooms, their material culture, and their associated visual and olfactory atmosphere have generally not been preserved in historic house museums.

As a third reason for selecting the Breuer papers: the entire collection is available online through the Archives of American Art’s website. At the beginning of the semester, I provided a brief in-class introduction on the availability of the Breuer papers, other Archives of American Art collections, and several additional digital archives. The value of the digital archive is that materials can be accessed remotely, at any hour of the day. Materials are therefore available to students who do not have time for lengthy visits to either a university special collections or other institution open only during standard business hours. This is particularly important for students with family obligations and/or with full- or part-time jobs in addition to their coursework, a profile that describes a significant percentage of the class. Using digital archives is perhaps a small but important way of recognizing that our students have demands beyond the classroom and that the idea of a student for whom coursework is the exclusive demand on their schedule is an outmoded idea. To require that students travel to archives during class sessions that, because of this travel, may extend beyond the designated course time allotment or may put students geographically far from their next scheduled obligation, or that they travel in person to repositories entirely outside of class time to start and continue research projects, puts additional and often unnecessary stresses on them. I brought to this use of digital archives an understanding of the importance of access based on my experience teaching for two years at a state university in northern Louisiana. Online primary source collections became a vital resource for undergraduate and graduate courses there, where students were distanced from resources not only through scheduling pressures but also through real geographic distance.

To respond to a possible concern that students would pose too broad or unresolvable questions: Yes, they absolutely would. The assignment encouraged thinking through the utility of primary sources as more than evidence supporting claims already made; instead, documents provided the impetus to make new claims. I anticipated—and told the class—that this would likely mean some questions would remain unanswered, while other questions would be quickly answered and demonstrate their limited usefulness in sustaining a long research investigation. We discussed how they were likely to find themselves running up against either temporary or permanent dead ends, owing to the potential limitations of time and resources afforded by a semester-long investigation.

In addition, this kind of assignment does require faculty to be available to mediate research concerns and talk through projects, a labor and luxury not always possible or even advisable for adjunct or term faculty or even for full-time faculty with teaching demands of 4-4 course loads or more. Given that enrollments of lower-level courses at community colleges and public universities can exceed one hundred students per course or even per course section, advising and evaluating individual student journeys into and through archives occupies a significant amount of time.6 That said, to offer some strategies for broader application: such investigations could be limited to just the initial document identification, contextualization, and posing of questions raised by the document. Or it could pair this extended “I wonder” exercise about the document with a shorter paper in which these questions are addressed: not necessarily answered, but instead discussed as to the strategies and resources students would employ if they were to answer these questions. Adapting these document investigations to group rather than individual projects is another possibility, cutting down on the number of presentations and papers and therefore reducing the quantity of feedback and grading required.

Feedback is important to this kind of project. Feedback from the course instructor and student peers both models and provides multiple ways of not just looking at but questioning sources. The purpose of the assignment is, in part, to encourage students to work on topics they might not have otherwise tackled and to provide them the permission to pursue research from perspectives they may have not otherwise considered. After the initial presentations, several students commented that they likely had not given their document enough consideration, since they did not have what they thought were the “correct” answers to questions posed by the class. I reiterated that they were not expected to have every answer at this point. Instead of taking questions as criticisms of their thinking, students were to take these questions as directed to and asked of the document. These questions were less prompts requiring answering in the moment than prompts for potential avenues to pursue over the course of their research, to themselves be turned over and evaluated. This was the overall goal of the assignment: certainly to use the archive as a site of rigorous research, but more so to catalyze curiosity for research. To situate primary sources as starting points instead of terminal points, as sites of questions instead of answers, as places that show us what is not there as much as what is there, is to promote not only the creation of new research but also, ideally, the creation of new researchers.

Cite this article: Andrew Wasserman, “Looking for What’s Not There in the Marcel Breuer Papers,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2167.

PDF: Wasserman, Looking for What’s Not There

Notes

- Whitney A. Martinko, “Progress and Preservation: Representing History in Boston’s Landscape of Urban Reform, 1820–1860,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 2 (June 2009): 304–34; Maurie D. McInnis, “Mapping the Slave Trade in Richmond and New Orleans,” Buildings and Landscape: Journal of the Vernacular Architectural Forum 20, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 102–25; Daniel Bluestone, “Chicago’s Mecca Flat Blues,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 57, no. 4 (December 1998): 382–403; and Kate Brown, “Gridded Lives: Why Kazakhstan and Montana are Nearly the Same Place,” The American Historical Review 106, no. 1 (February 2001): 17–48. ↵

- Marcel Breuer papers, 1920–1986. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/marcel-breuer-papers-5596. ↵

- Stuyvesant Six {housing development}, New York, New York, 1943–1944, box 8, reel 5720, frames 264–73, Marcel Breuer papers. ↵

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, 1963–1981, letters and contracts, box 21, reel 5729, frames 393–417, Marcel Breuer papers. ↵

- Unlabeled photograph, box 34, reel 5738, frame 516, Marcel Breuer papers. ↵

- I want to thank Caroline M. Riley for raising this important, and often under-discussed, point at the 2018 AHAA Symposium, during the question-and-answer period of the panel on which an earlier version of this essay was presented. ↵

About the Author(s): Andrew Wasserman is an independent scholar