Kara Walker’s About the title: The Ghostly Presence of Transgenerational Trauma as a “Connective Tissue” Between the Past and Present

Kara Walker, the renowned and controversial African American artist, was the subject of a major survey exhibition, Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love, which was organized by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and was presented there from February 17, 2007 through May 11, 2008; the exhibition also traveled to the ARC/Musée d’art Moderne de la ville de Paris, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, and then to the UCLA Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Not included in the exhibition was a complex, mural-sized drawing by Walker that is a promised gift to the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art.1 The work, created in 2002, bears a lengthy, narrative title that is also a description: About the title—I had wanted to title this “sketch after my Mississippi youth” or “the excavation” as I pictured it a sort of introduction to the panorama to come. However the image, which is partly borrowed, is of an Indian mound—painted by Mr. J. Egan in 1850 is meant to remind the dear viewer of another place altogether, from which we suckle life. Perhaps my rendering is too subtle . . . , (fig. 1). Walker explained that she felt that the drawing lacked a “connective tissue . . . to the rest of [her] work,” and she did not want it included in this survey exhibition.2

A detailed examination of About the title follows, and in it I employ trauma theory as one approach among many, while also considering the historical precedents and specific referents engaged by this work. This examination is combined with both a close visual analysis and attention to the title, as well as a consideration of material facture in terms of its makeup as a pencil drawing constituting six separate sheets of white paper pasted together. I will explain how this work conveys a traumatic history by way of its formal qualities and content.

In this “history drawing,” as I will call About the title (in contrast to “history painting” in the Grand Manner), Walker represented two nearly life-size figures flanking the central scene of an Indian mound excavation. A white man with top hat, long black jacket, and goatee stands in profile on the left—the slave master—and a black woman in a white dress stands on the right—an enslaved person. Although these figures frame the composition and echo one another, they are antithetical in skin color, clothing, stylistic rendering, pose, facial expression, and demeanor. The body, head, and hat of the standing white man exist as white nothingness outlined in light black pencil, while his jacket consists of a flat, tightly sketched, black plane. Walker reversed the light/dark dynamic in the African American woman on the right: the body is dark, while her flowing dress, curly hair, and disproportionately large hands are delicately outlined against the white ground. Her beautiful, loosely rendered facial features, supplicatory gesture, mournful expression, curvilinear contours, and flowing garment contrast sharply with the slave owner’s angular stance, severe if handsome profile, and stern expression. Her exposed breast suggests vulnerability and oppression, underscored by the manacles attached to her upper arms. A chain connecting the manacle on her right arm to her nipple pierces it like a ring (suggesting physical pain and torture). The other manacle connects to her back.

These framing figures are not only larger, but also more sculptural than those in the mound. Here the top three layers comprise the buried remains of several prostrate skeletons. Rather than suggesting a scientific drawing of an actual excavation, Walker instead drew a complex array of activities that go beyond documentation to imagine fantastical and disturbing events. Characteristically, these involve, in the lower section, disquieting scenarios of sexual activities, including a black woman performing fellatio on a white man, while another man penetrates her anally with an ax.3 Other disturbing scenes take place: in the background a man gropes a naked woman from behind, in front of them a man shoves another man into a hole; to the right a man attacks a skeleton with a whip; and in the extreme right a woman slides with abandon down the side of the mound interior with her legs spread high.

Walker also rendered the indigenous skeletons as active; one offers a cup of coffee to a surprised worker, adding a coy and playful element to an otherwise morose scene, while another seems to be in a position of prayer. Both dead and undead, the remains fail to stay submerged in the ground, but instead appear as mobile, animated bones that haunt the excavators—as well as the contemporary viewer of Walker’s history drawing.4

Walker’s well-known silhouettes, such as Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart, 1994, (fig. 2) and The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven, 1995, (fig. 3), recall and reinterpret the trauma of slavery, restating historical memory and forcing viewers to bear witness to her world of racial oppression and suffering on pre-Civil War plantations. Walker filled that world with obscene, haunting, and arresting images, all situated within the politics of race and interracial and intraracial desire. As a result, in her silhouettes, drawings, magic lantern shows, collages, watercolors, and video animations, she realized what art historian Gwendolyn Dubois Shaw calls the “discourse of the unspeakable”: “a discourse made up of the horrific accounts of physical, mental, and sexual abuse that were left unspoken by former slaves as they related their narratives and unfathomable bits of detritus that have been left out of familiar histories of American race relations.”5

Although Shaw argues that Walker remembers and reinterprets trauma in specific silhouettes and watercolors, I expand upon this by distinguishing among individual, transgenerational, and transcultural traumas in a work she does not discuss.6 Individual trauma is that which is directly experienced by a person initially whole or unified, who becomes, as a result of a traumatic experience, injured and ruptured, often unable to break free from the continuous, haunting return of fragmented and terrorizing memories that are manifested in flashbacks and nightmares, among other things.7 In other words, a trauma victim lacks the emotional, physical, and literal connective tissue within the neurons of the brain, often resulting in the lack of memory.8 In contrast, transgenerational trauma suggests a relationship of generations to powerful, often traumatic experiences that preceded their births, but were nevertheless transmitted to them so deeply as to seem to constitute memories in their own right, though they can never be fully understood or recreated.9 It therefore goes beyond the experience and chemistry of an individual to connect with subsequent generations, forming a major theme in this work, as it does throughout Walker’s oeuvre. This links with Toni Morrison’s term “rememory” in her 1987 novel Beloved, which according to Marianne Hirsch, “is neither memory, nor forgetting, but memory combined with (the threat of) repetition.”10 It is repressed history that remains present and active for descendants of individual traumatized victims: whether familial or cultural kin.

In this work, Walker added yet another type of trauma—transcultural trauma—experienced by enslaved African Americans and indigenous peoples. In other words, trauma, in this work, is not just personal, but transgenerational and transcultural, in ways that defy any neat categorization of racial identity and experience. After all, here Walker moved beyond a white/black binary to include references to the problematic and forced contributions of enslaved Africans to the traumas experienced by native peoples, creating a connective tissue between African Americans and natives and between the past and present. As Ron Eyerman persuasively argues about trauma and slavery:

The trauma in question is slavery, not as institution or even experience, but as collective memory, a form of remembrance that grounded the identity-formation of a people. . . . There is a difference between trauma as it affects individuals and as a cultural process. As a cultural process, trauma is linked to the formation of collective identity and the construction of collective memory. . . . Slavery was traumatic in retrospect, and formed a “primal scene” that could, potentially, unite all “African Americans” in the United States, whether or not they had themselves been slaves or had any knowledge of or feeling for Africa.11

Furthermore and significantly, About the title expands the scope of Walker’s condemnation of racial politics in the United States—which usually refers to the perversity of slavery in the pre-Civil War antebellum past and its effect on the present—to also implicate the debasement of native cultures, specifically in the portrayed defilement of indigenous remains. Walker may have wanted to exclude this work from the survey exhibition because of concerns about “speaking” on behalf of indigenous peoples as a black woman and the fact that no other work in her oeuvre addresses experiences of other marginalized groups. But, it nevertheless represents the hopeless and helpless repetition of trauma among individuals, generations, and cultures, which existed for both enslaved and native peoples as a result of colonial imperialism that involved Africa and the New World: the exploitation of labor, sexual violence, forced severing of historical connections to ancestral grounds, loss of cultural continuity, and breaking up of families. In this work, Walker broadened her powerful, longstanding critiques (e.g. of the transnational slave trade, Southern slavery, and post-Civil War racism) to include also European American colonialism and imperialism, which I contend is referenced in this unfamiliar work.12 In other words, About the title uniquely embodies anti-colonial discourse as an extension of her better-known anti-racist discourse and alludes to contemporary issues of repatriating native remains. In this way, it both extends and complicates Walker’s larger oeuvre.

Walker’s use of the term “connective tissue” takes on additional meanings in opposition to her intent in explaining why she did not want this drawing included in her survey exhibition: there are connections between this drawing and Walker’s oeuvre, this drawing and traditions in western art history, this drawing and its title, between different oppressed cultures, between the past and present, and between separate pieces of paper pasted together. Another connection is the repetition of traumatic effects across time and cultures that also apply to family bonds and the bonds of slavery.

Walker added the treatment by European American settlers of indigenous peoples to her discourse of the unspeakable trauma acted out on the enslaved. The natives are represented here by the callous exposure and exploitation of their remains, which literally are not whole or unified, but injured, fragmented, and ruptured—and therefore lack connective tissues. She rendered what Dominick LaCapra calls the “aftereffects” of trauma—“the hauntingly possessive ghosts” that are “not fully owned by anyone,” but that “affect everyone”—in this case not only blacks, but also native peoples and whites.13 Walker went back over the problem of slavery and the mistreatment of indigenous peoples, worked it over, and transformed its understanding in a non-linear development that moves incessantly between various historical pasts and the present, indicating that these traumas are not located entirely in the past, but are alive in the present, like a connective tissue.14

Darby English argues that Walker’s silhouettes and projected lanterns compositionally collapse past and present and images and viewers into a spatial and temporal continuum.15 As presented in Gone and End of Uncle Tom, as well as About the title, her works contain an unfocused compositional space with no clear foreground, middle ground, and background, lack of appropriate scale for figures and objects, and white empty space surrounding the figures and landscape motifs. This treatment of time and space results, according to English, in a temporal impermanence that contributes to the audience’s ability to find and experience trauma as a “lived history” in the present.16 Consequently rather than achieve resolution, healing or closure, Walker’s works instead suggest the haunting continuation of trauma as a connective tissue across generations as a “rememory.” Trauma ironically enacts a disruption and the cutting of ties, on the one hand, and a connective tissue across time and people by way of transgenerational trauma, on the other.

The fragmented yet joined pieces of paper further convey both disruption and cohesion. The lines between the adjacent pieces of paper remain visible, creating clear vertical divisions in the composition between the flanking figures and the central burial mound. In addition, the visible horizontal line between the three upper and three lower sheets divides the top two registers of the mound and the bottom area. The fragmentation implied by the visibly joined paper relates to the trauma subject as broken. At the same time, however, that subject seeks psychological wholeness, or connective tissue, which is manifested in the material work itself that appears as a single, whole piece of paper from a distance.

Walker’s ghostly and shadowy silhouettes and drawings of African Americans, indigenous remains, and whites deliberately evoke these aftereffects of trauma, representing the unspeakable, and thereby signifying an absent presence whose traces appear as evident and haunting in American culture. As Cathy Caruth explains, “the striking juxtaposition of the unknowing, injurious repetition and the witness of the crying voice” demands a listener or viewer “for the belated repetition of trauma” that can only be known after the traumatic event.17 In About the title, Walker created a repetitive traumatic site—the belated repetition of trauma—by way of the illustration of successive injuries inflicted by slavery, European American colonialism, expansion, and destruction of indigenous sites. She then challenges the “dear viewer” to witness, acknowledge, and remember all of those separate and interrelated traumas of slavery, westward expansion, and racism—the shadowy ghosts that still haunt us today.

The Ghostly and Shadowy Presence of Colonization, Slavery, and Trauma

The figures in About the title, like Walker’s signature silhouettes, function as what sociologist Avery F. Gordon has called “ghostly presences.” Coining the term in her analysis of what she calls “ghostly matters,” Gordon expounds on “the ghost or the apparition,” “one form by which something lost, or barely visible, or seemingly not there . . . that makes itself known or apparent to us.” Gordon views “the ghostly haunt” as giving “notice that something is missing—that what appears to be invisible or in the shadows is announcing itself.”18

I argue that the “ghostly presences” of Walker’s silhouettes and drawings expose, in Gordon’s words that she applies to modern social life, “hauntings, ghosts and gaps, seething absences, and muted presences.”19 On the level of technique, the silhouette and pencil drawing processes enabled Walker to create works that meet the very definition of a ghost: “faint shadowy trace[s]” that can never be erased and which mark “that which is present, but that which is absent but still detectable in absence,” “an absent presence.”20 “Ghosting” happens as the simultaneity of revelation and concealment, making something visible and invisible. On the level of subject matter, these absent presences are the acts of abuse experienced by natives during the age of colonization and expansion and by those enslaved during the Middle Passage and on plantations. Walker enabled these acts to become visible as traces or shadows whose presence on the walls of a gallery or museum haunts the viewer, forcing one to acknowledge and to remember. At the same time, Walker’s silhouettes and drawings appropriately represent, in the artist’s own words, the “shadows of artificial things, shadows of stereotypes, shadows of things that maybe there’s only a written description of.”21

Although Walker created About the title as a drawing and not a silhouette, the larger figures in the work, who flank the central burial mound, emulate the positive/negative polarity found in the medium of her signature silhouettes, creating another connective tissue to her oeuvre. Walker called the latter medium “a benign little craft.”22 In About the title, she again transformed a “benign little craft” into a heroic scale; with life-size figures and the theme of suffering, the drawing emulates history paintings, a genre to which she, as a woman and an African American, would not have had access in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when only white men could create works in the Grand Manner. Yet the absence of heroic action gains significance in her genre: history drawing. In contrast to the subjects of history paintings done in the Grand Manner, Walker’s black-paper figures and the persons depicted in her history drawing appear as neither heroic nor evil, but in the words of the artist, a a “dot, dot, dot . . .”23 This leaves an open ended meaning that the artist deliberately refuses to explain.

At the same time, the pencil drawing contains sketchy and subtle shadowing and discrete linear boundaries for objects and figures, creating a haunting and ghostlike presence. Areas of untouched white paper form the body of the African American woman, the legs of the white excavator, bodies inside the mound, and areas of the landscape. Here the artist formed faint, ghostly, shadowy presences that embody the simultaneity of revelation and concealment—in this case referring to something now visible in the drawing, through the excavation and cross-sectional view, which had once been invisible, literally buried inside the earth.

In her representation of shadows, Walker forces us to notice that race, racism, and violence against African American male and female bodies have always been present in the shadows of American culture and history. She significantly added to this the mistreatment of indigenous remains, enlarging her critique of racism and violence against another minority race by appropriating her central scene from “Mr. J. Egan.”

Walker’s References to Egan’s Panorama and Traditions in Western Art History

In her lengthy title, Walker informs “the dear viewer” that she “partly borrowed” her image from an obscure mid-nineteenth-century Irish-American artist who had created a vast panorama “in 1850.” About the title therefore occurs as another of Walker’s fantastical transformations of a previous source—John J. Egan’s multi-paneled, 348 foot-long Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley, 1850—that she could have seen in the Saint Louis Art Museum, or more likely, as Walker vaguely recalled, in a textbook.24 Another connective tissue exists now between the work she may have seen and her sardonic revision of it. Walker’s extensive title functions as a description of what Walker represented in the drawing: a cross section of an “excavation . . . of an Indian mound.” Walker actually derived her composition from one vignette in Egan’s enormous panorama: Opening a Mound, scene twenty, (fig. 4).25

A person not mentioned in Walker’s title who plays a significant role in her appropriation is Montroville Wilson Dickeson. He was a physician in Natchez, Mississippi, and a decade later served as professor of natural science and director of the city museum of Philadelphia. Dickeson assisted in research-oriented excavations—what contemporary handbills advertised as “Aboriginal Monuments” and “Antiquities & Customs of the Unhistoried Indian Tribes.”26 Besides advocating cross-sectioning of Southern Mississippi Valley mounds during the1840s, he commissioned Egan to produce this biographical and scientific visual document, which he exhibited and about which he lectured.27 Egan modeled his composition on Dickeson’s field studies, while the doctor took the panorama on tour in darkened theaters in Philadelphia and throughout the Mississippi Valley to raise money for additional digs.28

Egan’s work—the model for Walker’s history drawing—shows a rounded, dome-shaped structure built during the third moundbuilding epoch (AD 700–1731) and discovered later in the first half of the nineteenth century on the plantation of William Feriday in Concordia Parish, Louisiana.29 In his panorama, Egan alludes to the moundbuilders myth—the belief that native people had replaced a peaceful agrarian prehistoric culture prior to the appearance of Europeans in the New World. In the 1830s and 1840s, historians and archaeologists debated the true descendants of the indigenous moundbuilders. Were they contemporary indigenous peoples, as some argued, or were the original moundbuilders members of a superior race or even the lost tribe of Israel, who were later replaced by the ancestors of contemporary tribes? This latter position is the myth perpetuated in Egan’s view that living indigenous populations had replaced an ancient and peaceful agrarian civilization, and so suggested a kind of indigenous precedent for latter-day acts of displacement enacted by Anglos. Such statesmen as Andrew Jackson, the author of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, employed the myth as grounds to expel indigenous tribes from territories east of the Mississippi River in the name of imperial expansion. This cultural displacement of the moundbuilders by Native Americans, and the Native Americans by European American settlers, would demonstrate how trauma and traumatic behavior, and in this case repeated behavior which is a symptom of trauma, gets passed down through generations. Trauma exists, as Caruth explains, “as an endless necessity of repetition,” a “repetition compulsion,” and “the determined repetition of the event of destruction.”30

Egan’s brightly colored landscape shows this cross section of an Indian mound being excavated by eight enslaved blacks under the paternal guidance of two white men who are located in the center foreground. Another white man seated on the left, probably Dickeson, sketches, while black laborers wield shovels and axes to unearth the skeletal and material cultural remains of the Indian mound. In fact, ethnographic excavations like Egan’s did use the hard labor of Southern African American slaves, a practice begun by Thomas Jefferson on his plantation.31 Situated in this bucolic landscape, outside the mound and to the right of the composition, are white women accompanied by men. Dressed in ladylike finery, the women’s deportment seem more appropriate to a tea party or picnic. At the right, indigenous families before two tepees appear oblivious to the excavation.32

Like Egan, Walker also depicted a cross section of an excavation of an Indian gravesite. Both Egan’s and Walker’s panoramas dramatize a history of multiple postcolonial dispossessions: unnamed earlier denizens by indigenous peoples and Native Americans in turn by white settlers. Both also combine nostalgic and pastoral scenes with violent histories, which typifies nineteenth-century panoramas of the Mississippi River when, as Shelly Jarenski explains, “both slavery and Indian removal produced a sense of racial and spatial tension.”33 The concept of ghosting, discussed above, becomes useful in reference to the calculated amnesia or historical denial expressed in the myth of the moundbuilders, which denied the cost and violence of white expansion. This episode is a different chapter of the story of violent dispossession and uprooting that Walker addressed in her works dealing with the African Diaspora. Walker interrogated Egan’s presumed expansionist mythmaking, connecting the white man’s excavation and destruction of an ancient culture with his misuse of African slaves to uncover and exploit it. Moreover, she corrected Egan’s vignette, which omitted the plantation overseer and absent whip, to instead include the plantation owner and chained enslaved woman.

The drawing acknowledges the complex power relationships involved in using enslaved labor to excavate ancestral native land, which is further complicated by the fact that some tribes owned black slaves. According to present-day historians, the descendants of the moundbuilders probably have particularly close ties to the Cherokees who had owned slaves: native-born slaves during an era of the deerskin trade and later, with the rise of the plantation system, African slaves.34 The mistreatment by slaves of the Native American remains pictured in Egan’s and Walker’s murals fail to show that some tribes actually owned African slaves who worked their lands too. Native Americans and African Americans can therefore be genealogically intertwined, assuming that the mixing of races took place, forming yet another connective tissue between the two races.

Significantly, Walker did not follow Egan’s precedent in including living tribal families in front of their tepees. Certainly their ancestors had buried these remains. By excluding living Native Americans, Walker may have intended to form a relationship between contemporary issues of repatriating native remains and the use of a nineteenth-century source that involves a form of “grave robbing” or the desecration of their remains. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), enacted on November 16, 1990, addresses the rights of lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations to indigenous cultural items. These include human remains. By showing white Americans and the enslaved desecrating indigenous remains in the past, Walker exposed how this had occurred earlier in the nineteenth century when laws failed to protect such invasive and damaging excavations.

The nearly life-size framing figures of slave owner and enslaved woman serve as master narrators of the scene, a function suggested by their extended arms and position on either side of the mound cross section. The slave master with a bulging erection visible beneath his pants suggests his perverse sexual arousal over the excavation to which he points and to the revelation of sexual activities and skeletal remains. While the white man appears as a sexually virulent cruel oppressor, the woman seems kind, gentle, and caring, while also sexually vulnerable. Significantly, she gestures imploringly toward the central scene as if calling our attention to the egregious acts presented there.

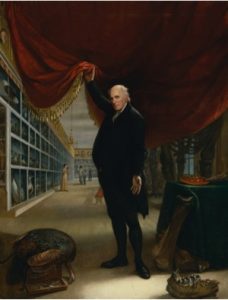

Walker’s pictorial strategy, like that of Charles Willson Peale in his Artist in His Museum, 1822 (fig. 5), as Roger Stein explained about the nineteenth-century painting, “was to make the process of seeing self-consciously part of the expressive design of the” work, “to call our attention to our visual experience rather than to make [the] picture a transparent window into the universe.” Peale accomplished this by representing himself as “the artist-scientist-director” lifting a curtain to reveal the botanical, biological, and archaeological contents of his museum, which had a formative impact upon Dickeson’s archaeology. Walker, however, did not include herself, but instead inserted two other figures—the slave and slave master—to function, like Peale, as narrators offering a view of a different drama and scientific history. These framing figures replace Peale’s curtain in defining the “boundary between inside and outside, between the constructed world of art and artifice, and life.”35 In this case, the distinctions between artifice and reality and between the third moundbuilding epoch and the nineteenth century appear fluid. Whether Walker knew that Dickeson visited Peale’s museum in the 1850s and purchased some of his collection is immaterial to the larger point: this historical fact gives her reinterpretation of the Philadelphia artist’s painting additional significance, forming yet another connective tissue that also exists with Peale’s Exhuming the Mastodon (1805–8; The Peale Museum, Baltimore City Life Museum).36 Here Peale documented an actual event that occurred in upstate New York when he discovered fossilized skeleton bones from an extinct mastodon, which figures prominently in his later Artist in His Museum. Egan, Peale, and Walker each rendered historical scenes of excavations of bones to unearth covered remains and histories of supposedly extinct species/people. Walker, however, did this to expose the transcultural and transgenerational trauma among minorities.

The framing figures also invite an additional comparison derived from artistic conventions that predate Peale and Egan. Walker’s composition can be read as a triptych, with the flanking man and woman replacing the saints or patrons typically found in Byzantine and Renaissance altarpieces. The mound in this case would represent the primary scene of Christian art: the Crucifixion. Like the Virgin in Albrecht Altdorfer’s Crucifixion (fig. 6; c. 1512–14; Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel) who looks at the viewer in a sorrowful manner, Walker’s enslaved woman also looks outward with a poignant, beseeching expression. Here, rather than Christ suffering to save mankind, the artist depicted the bodies of white women, African Americans, and native people who suffered. Their suffering, however, does not result in salvation. It repeats the repetitive cycle of trauma without deliverance from harm, ruin, or loss, binding cultures together in shared rememories of past traumas.

This drawing, like Walker’s silhouettes, deconstructs the aesthetic and imperialist discourse that prevailed in nineteenth-century panoramas such as Egan’s. As Jarenski argues about Walker’s resurrection of these past forms, the “panoramic aesthetics” contain “racialized pedagogical power”; in other words, they encourage contemporary African American artists to engage with and deconstruct historical genres. Walker notably included the enslaved experiences that these earlier panoramas had excluded. She intentionally recovered and inserted these experiences and response to the excavation of Indian mounds for historical accuracy to expand her critique of this history. In About the title, Walker again collapsed past and present, but now to deconstruct and critique the imperialist agenda of nineteenth-century panoramas that served to promote westward expansion and the conquering of land: an agenda that relied on enslaved labor and the co-traumatization of different oppressed people.37

Like the Native American artist James Luna in his 1986 performance, The Artifact Piece, she challenged the myth of the “Vanishing American”: that indigenous peoples became extinct during the westward expansion. Luna installed himself in an exhibition case in the San Diego Museum of Man in the section on Kumeyaay Indians, including a variety of personal items in the display: ritual objects he uses on his La Jolla a reservation, shoes, political buttons, an album of the Rolling Stones, his divorce papers, and other personal artifacts. He commented: “we were simply objects among bones, bones among objects, and then signed and sealed with a date” by excavators, such as the ones pictured in Walker’s drawing.38 Like Luna, Walker focused on what he calls “intercultural identity.”39 A connective tissue therefore exists between these two artists who deal with their racial heritages and white American racist attitudes.

Walker conflated past and present also by way of style and content. The framing figures signify the past through both their clothing and their style of depiction, with the rigid profiles, concise contours, flatness, and awkward proportions found in nineteenth-century naïve art—the period in which the excavation took place. Yet the ancient burial sites predate this period, marking the antiquity of the “New World,” an era prior to the settlement by European Americans and the enslavement of Africans. Walker, on the other hand, created the work in the recent past and we view it in the present, focusing on the drawing as well as its title, upon which I now elaborate.

The Meaning(s) of Walker’s Title(s)

The characteristically verbose and complex title is part of the work itself, and enables us to further unpack the complex meanings within this history drawing.40 When the drawing had been exhibited, the title appeared on a framed blue index card directly to the left of it, (fig. 7). The small size of the title, the space between the two framed “texts,” the difference of color and no color, the distinction between typed words and drawn images—all these qualities make the title stand apart from the visual representation. For Walker, “the word is a completely separate thing” that “really sits off to the side,” which is the case here.41 The text exists as an element of the work, separate from, yet connected to the drawing. By combining and separating word and image, insisting that the title appear beside the drawing, containing both texts within black frames, and drawing/writing both image and text in black pencil or black typewriter ribbon, Walker clearly calls on “the dear viewer” to pay attention to both “antiquated mediums.”42 Walker claimed that her texts of artworks hold “a strange thread” that connects “from writing to image to writing again,” forming another connective tissue that is manifested here.43

This descriptive title departs in some ways from the ones Walker gave her tableaux such as Gone and The End of Uncle Tom. The latter derives from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1852, while Walker’s title for Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart combines portions of Margaret Mitchell’s title Gone with The Wind, 1937, and Thomas Dixon, Jr.’s The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, 1905.44 In her titles, Walker also wryly constructed a fictitious historical personality, what she called “the invented construct” for the artist/author—“Miss K. Walker, a Free Negress of Noteworthy Talent.” 45 This persona appears in other works such as “Kara Elizabeth Walker” and “the Young, Self-Taught Genius of the South Kara E. Walker.”46 Although the “Negress” is not named as the artist in the title of About the title, she nevertheless is present in the form of the nearly life-size enslaved woman on the right who resembles Walker’s persistent stock image whom she described as having “grotesquely large lips” and “dirty ribbons” in her braided hair. The “Negress” can also be found, for example, in End of Uncle Tom—who also appears as her proxy in those works.47 The title, moreover, mimics the wordy and lengthy ones of nineteenth-century panoramas, imitating their awkward, much punctuated syntax with long phrases that directly address her audience.48

Walker similarly included the mimetic authenticity of nineteenth-century panoramas, by calling “this “work, About the title, a “sketch after my Mississippi youth.” In the accompanying booklet to James Presley Ball’s Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States, 1855, for example, he claims the panorama was “taken by the artist upon the spots which they represent.”49 This statement provides, according to Jarenski, a sense of “evidentiary truth” just as Walker’s ownership does.50 Panoramas call on proof in two ways: suggesting that their authors (often through the conceit of a sketch) presented sights that they had authentically witnessed, and offering viewers the chance to see these scenes themselves. Experience, then, seems to be a principal vector of the visual/material rhetoric of panoramas: of the author and the viewers, resulting here not in rememory, but instead, in experience and re-experience.

Rather than naming herself as Miss K. Walker, Kara Elizabeth Walker, or Kara E. Walker as she did in other titles, she instead referred to herself through the possessive adjective, “my,” assuming the viewer’s familiarity with the artist, and/or bewilderment about who actually sketched the drawing. Walker’s claim in the title that she created the work during her youth suggests that once again, she constructed a fictional artist, for she grew up not in Mississippi, but in Stockton, California, and later in Stone Mountain, Georgia, the site of the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915, and of notorious lynchings. In the title of the history drawing, as on other typed note cards, she created what she referred to elsewhere as “a voice that seems to shift character in midsentence,”51 or in this case, amid sentence and phrases.

In her title, by using the first person and the possessive adjective both twice, Walker set in motion a series of paradoxes that encompass the state of both/and in terms of authorship. Both Walker and Egan, both an African American artist and a European American one, both a woman and a man, sketched this work in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries respectively.

Walker’s extensive and complex title includes words with specific meanings that elaborate upon the traumas the artist has reenacted. “I had wanted to title this . . . excavation” suggests a multitude of connotations. The word “excavation” means to “make hollow by removing the inside”; “the action or process of digging out a hollow in the earth”; “to form or make (a hole . . .) by hollowing out”; “a cavity or hollow”; and “an unearthing.”52 It certainly refers to the actual digging away to uncover what had been buried, an excavation in the past that Walker has drawn. The activity of excavation itself becomes a metaphor for excavating or unearthing wrongs, but this takes place at the sacred burial site of another culture, signifying an additional violation—now against the indigenous body and culture. Here, however, African Americans, pictured as assisting in digging up native remains, must cooperate with the destruction of the culture of the indigenous peoples.

Her “dear viewer,” however, cannot imagine trauma as residing solely in the past, but instead witnesses it as relentlessly and continuously invading the present. Therefore the word “excavation” in the title also refers to the artist’s digging out egregious aspects of United States history—not to remove them, but to expose their haunting, ghostly, and shadowy presences in the present as a “rememory.” At the same time, her history drawing of an excavation appropriately describes the recovery of painful and repressed traumatic memories that Walker reenacted in her panorama and reveals what occurs to the psyche of a trauma victim, suggesting that this wounded psyche impacts more than the individual to become a cultural phenomenon.

Walker’s title includes other words with specific meanings within her oeuvre that help to further clarify the traumas represented. Consider “from which we suckle life.” The act of suckling—“to nurse (a child) at the breast” and “to nourish”53—becomes complicated in her phrase, for she suggests that rather than providing nourishment, “we”—“the dear viewer” take away from “another place.” This certainly applies to the excavation in which the slaves and slave masters remove the native remains. At the same time, the enslaved woman’s seemingly swollen exposed breast could signify that she is in the process of nursing a baby, probably her own as well as that of the slave master and mistress; within this context, the white child now “suckle[s] life” by taking the enslaved mother’s milk intended for her own child. The drawing of the “panorama” indeed “remind[s] the dear viewer of another place altogether, from which we suckle life”: slavery and the nineteenth-century violence of indigenous peoples, a traumatic mistreatment that forms a connective tissue that adversely affects later generations.

Walker elaborated on the meanings of her nursing women in her various works:

My constant need or, in general, a constant need to suckle from history, as though history could be seen as a seemingly endless supply of mother’s milk represented by the big black mammy of old. For myself I have this constant battle—this fear of. It’s really a battle that I apply to the black community as well, because all of our progress is predicated on having a very tactile link to a brutal past.54

For her, the nursing “big black mamm[ies] of old” signifies literally how the artist “suckle[s] life,” by appropriating images, titles, and ideas from a history filled with racialized and sexualized topos, all of which become source material for her visual and textual imagination that indicate her inability to sever the link to the brutal past of slavery. Within this context, the mound itself resembles a breast that could be seen as both nurturing and imprisoning the buried and living bodies. The mound-as-breast, a black protrusion from the earth, echoes the enslaved woman’s white projecting breast. Both exemplify the topos of women-as-nature to suggest fertility. A connective tissue exists between Walker’s desire to “suckle from history” its “brutal past,” one that also refers to the brutal past of indigenous peoples who are buried within the mound-as-breast.

Performing an Act of Remembrance

Significantly, Walker represented just one scene from Egan’s panorama that originally contained twenty-five panels. In doing so, she deliberately disrupted Egan’s linear narration, suggesting another type of traumatic rupture; in other words, she selected just one panel from a continuous whole to embody traumatic woundedness and disruption in her own “panorama to come” that she never fully realized. The artist’s admitted inability to complete the panorama therefore exists as yet another signifier of trauma—the fragmented memories that can never be fully recovered. At the same time, this image from the past occurs, as Walker explained in an interview about her working method, at “a certain moment [when] a fissure and all the past comes flooding in.”55 The fissure of the past that floods into the present marks how trauma victims are, according to trauma theorist Ruth Leys, “haunted or possessed by intrusive traumatic memories represented as past, but . . . perpetually re-experienced in a painful, dissociated, traumatic present,”56 which I argue, results in the present by way of transgenerational trauma. This is manifested in a blog, in which an individual expressed her anxiety in having viewed this drawing:

Kara Walker’s art disturbs me. . . . This piece shook me out of my comfort level. I value Walker’s ability to force a deeper conversation and confront extremely uncomfortable themes of race, sexuality, power, bias and violence in the context of our past while also reflecting the realities of our present.57

Walker significantly ended her title in ellipses, suggesting an unfinished (and somewhat dismayed) thought that this viewer also articulated. These significant ellipsis marks in the title could indicate what the art historian Richard Meyer refers to within a different context as “secrets and structuring absences” that express “both ignorance and knowledge” and function as a kind of hole or wound in the text that cannot be filled in (or that Walker refuses to fill in).58 It performs the kind of impasse that trauma often creates—the place that one cannot get around, the site that embodies the unspeakable or visually indescribable nature of trauma.

By not including living natives in her composition, her work may be interpreted as reinforcing the timeworn view that they have become extinct as the Vanishing American. Indeed the workers and the enslaved blacks, by desecrating the Indian mound and its remains, attempt to remove traces of their existence, their cultural practices, and their monuments. Walker’s history drawing, however, clarifies that she refused to erase the past and accept the racial status quo; she instead “reminds the dear viewer of another place altogether,” a time during which whites attempted to desecrate and remove the existence of native peoples through the forced assistance of enslaved blacks. The drawing adds aggression against Native Americans to the artist’s many representations of historical violence, which suggests the transgenerational and intertwined histories of traumatic cultural displacement significantly suffered by both native peoples and enslaved African Americans. In other words, About the title indeed shares a connective tissue to her other works in its representation of transgenerational trauma and its disruption to the conventional United States histories that often romanticize the antebellum Southern plantation and, in this case, also the settlement of the West. In this work, she collapsed past and present, textual and visual, the fictional and actual to indicate that the past wrongs against African Americans and Native Americans still haunt “the dear viewer” as a “rememory.”

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to my colleagues in the year-long fellows’ program, “Trauma Studies,” at the Robert Penn Warren Center of the Humanities at Vanderbilt University (2008-2009) for assisting me in unpacking this topic and applying it to art history: Laura Carpenter, Claire Sisco King, Kate Daniels, Linda Manning, Jon Ebert, Charlotte Pierce-Baker, Maurice Stevens, and Christina Karageorgou-Bastea. I would like to especially thank Erika Doss, Leonard Folgarait, Claire Sisco King, Angela Miller, Charmaine A. Nelson, Annette Stott, Cecelia Tichi, and Rebecca Vandiver for their suggestions. Sarah Burns and Jennifer Marshall as editors of Panorama contributed greatly to the improved clarity and organization of the article. I am also grateful to Cecelia Tichi for introducing me to this work and for George A. Davis, Assistant Registrar of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, for providing information and arranging for me to view this work while it was in storage.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1537

PDF: Fryd – Kara Walker’s About the title

Notes

- The work has been exhibited five times at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angles: “Recent Acquisitions,” MOCA Grand Avenue, November 20, 2005–January 9, 2006; “Collecting Collections, MOCA Grand Avenue, “February 10–May 19, 2008; “Highlights from the Permanent Collection, 1980–2005,” MOCA Grand Avenue, May 20–August 11, 2008; “Collection: MOCA’s First Thirty Years,” The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, November 15, 2009–July 12, 2010; and “Selections from the Permanent Collection,” MOCA Grand Avenue, February 8, 2014–April 12, 2015. Details of the drawing can be found at “Artist a Day Challenge No. 17: The Kara Walker Challenge,” Cultureshockart, February 17, 2015, https://cultureshockart.wordpress.com/2015/02/17/artist-a-day-challenge-no-17-the-kara-walker-challenge/, accessed February 2, 2016. ↵

- Kara Walker to the author, November 24, 2010. ↵

- Public sex was common between sexual predators and black enslaved females as a means of oppression and humiliation; one example is the overseer Thomas Thislewood who raped/sexually coerced enslaved women under his care in Jamaica, often publically. See Trevor Burnard, “The Sexual Life of an Eighteenth-Century Jamaican Slave Overseer,” in Sex and Sexuality in Early America, ed. Merril D. Smith (New York: New York University Press, 1998). ↵

- As David Wall observes about some of the artist’s other works, Walker forces the viewer into “a similar traumatic confrontation with that violent and terrible space between life and death, being and non-being, black and white, slave and master, voyeur and object” where “we are made conscious of the surplus of meaning routinely hidden, the excess of desire, fear, trauma, and self-hatred that is the cornerstone of racial representation.” See his “Transgression, Excess, and the Violence of Looking in the Art of Kara Walker,” Oxford Art Journal 33 (October 2010): 292. ↵

- Gwendolyn Dubois Shaw, Seeing the Unspeakable: The Art of Kara Walker (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 7. For others who address sexual exploitation of black women in slavery, see, for example, Deborah Gray, White Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1999); Hilary McD. Beckles, “White Women and Slavery in the Caribbean,” in Caribbean Slavery in the Atlantic World: A Student Reader, Verene Shepherd and Hilary McD. Beckles, eds., chapter 47 (Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle, 2000); Ann duCille, “‘Othered’ Matters: Reconceptualizing Dominance and Difference in the History of Sexuality in America,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 1 (July 1990): 102–27; and Burnard, “The Sexual Life of an Eighteenth-Century Jamaican Slave Overseer.” ↵

- Shaw discusses trauma in Seeing the Unspeakable, especially within the context of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 42, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, 46, and particular figures in The End of Uncle Tom, 42, 46, 48–-49, 52, 61, 65. She maintains that slavery “is arguably the most pervasively traumatic, guilt-ridden episode in U.S. history,” 39. ↵

- E. Ann Kaplan, Trauma Culture: The Politics of Terror and Loss in Media and Literature (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005), 19. ↵

- For a neuropsychological study of how memories bypass the cortex to be situated instead in the amygdala, the “flight and flee” area of the brain, see Stephen D. Smith, Bassel Abou-Khalil, and David H. Zald. “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in a Patient with No Left Amygdala.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 117 (May 2008): 479–84. See also Susan Jarosi, “Traumatic Subjectivity and the Continuum of History: Hermann Nitsch’s Orgies Mysteries Theater,” Art History 36 (September 2013): 849. ↵

- Kaplan, Trauma Culture, 106. ↵

- Marianne Hirsch, “Maternity and Rememory: Toni Morrison’s Beloved,” in Representations of Motherhood, ed. Donna Bassin, Margaret Honey, and Meryle Mahrer Kaplan (New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 1994), 96. See also Caroline Rody, “Toni Morrison’s Beloved: History, ‘Rememory,’ and a ‘Clamor for a Kiss,’” American Literary History 7 (Spring 1995): 92–119. She interprets “rememory” as functioning in Morrison’s “’history’ as a trope for the problem of reimagining one’s heritage,”101–2. ↵

- Ron Eyerman, “Cultural Trauma: Slavery and the Formation of African-American Identity,” in Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, eds., Jeffrey C. Alexander, Ron Eyerman, Neil J. Smelser, and Piotr Sztompka (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 60. ↵

- The material on postcolonialism is vast, but for a discussion of it in relation to African American art and slavery, see for example Charmaine A. Nelson, The Color of Stone: Sculpting the Black Female Subject in Nineteenth-Century America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); and Charmaine A. Nelson, Slavery, Geography and Empire in Nineteenth-Century Marine Landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica, (London: Ashgate, 2016). ↵

- Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, Writing Trauma (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), xi. For a discussion of Kara Walker’s film and video work and how she creates a repetitive traumatic site that surrounds, involves, and challenges the viewer to witness, acknowledge, and remember the individual and transgenerational trauma of slavery and contemporary racism in the United States, see Vivien Green Fryd, “Bearing Witness to the Trauma of Slavery in Kara Walker’s Videos: Testimony, Eight Possible Beginnings, and I was Transported,” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 24 (February 2010): 145–59. ↵

- LaCapra explains that “working through . . . means coming to terms with the trauma, including its details, and critically engaging the tendency to act out the past and even to recognize why it may be necessary and even in certain respects desirable or at least compelling.” He distinguishes between acting out, a repetitive process “whereby the past … is repeated as if it were fully enacted, fully literalized,” and working through, which “involves repetition with a significant difference . . . (it) is not linear, teleological, or straightforward developmental . . . process . . . . It requires going back to problems, working them over and perhaps transforming the understanding of them. See La Capra, Writing History, 144–48. ↵

- Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 71–136. ↵

- Ibid., 82. Also see Shelly Jarenski, “‘Delighted and Instructed’: Panoramic Aesthetics and African-American Challenges in J. P. Ball, Kara Walker, and Frederick Douglass,” American Quarterly 65 (March 2013): 139. Jarenski similarly argues that “much like an encounter with a panorama, the experience of being taken in by an image is equated with space; the critic imagines he is somewhere else, in a space and time separate from real space and time. His sensory perception and awareness of the outside world, of the natural horizon, are eliminated, and the image becomes the source of the real. However, the experience of the real space and time is not replaced with a comforting illusion that approximates reality, as it would be in a traditional panorama, nor are the troubling sensations of leaving the real placated by suturing linear narration.” ↵

- Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 204. ↵

- Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 8, 15. ↵

- Ibid., 21. ↵

- Webster’s Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary, 352 and 809. Carolyn Dever addresses the meaning of the noun and verb “trace” in Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White, 1859–60, addressing Derrida’s discussion of this word as “a signifier of absent presence.” Quotations about the meaning of “trace” derive from her text. See Carolyn Dever, Death and the Mother: From Dickens To Freud Victorian Fiction and Anxiety of Origins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 117–21. See also Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Baltimore, MD.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), 61, 65, 145. ↵

- “The Melodrama of ‘Gone with the Wind,”’ Kara Walker: Art in the Twenty-First Century, http://www.art21.org/texts/kara-walker/interview-kara-walker-the-melodrama-of-gone-with-the-wind, accessed June 3, 2005; and Jerry Saltz, “Kara Walker: Ill-Will and Desire,” Flash Art 29 (November–December 1996): 82. ↵

- Sidney Jenkins, “Interview with Kara Walker,” in Look Away! Look Away! Look Away! (Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, 1995), 11. ↵

- “Projecting Fictions: Insurrection! Our Tools Were Rudimentary, Yet We Pressed On,” Art in the Twenty-First Century, http://www.art21.org/texts/kara-walker/interview-kara-walker-projecting-fictions—insurrection-our-tools-were-rudimentary- accessed May 12, 2005. ↵

- Walker claimed she “probably” saw a reproduction of Egan’s image “minutes before I drew the drawing,” Walker to the author, November 24, 2010. For history texts that illustrate this particular vignette, see Robert Silverberg, Mound Builders of Ancient America (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1968), 99; George E. and Gene S. Stuart, Discovering Man’s Past in the Americas (Washington, DC: Washington National Geographic Society, rev. ed. (1969; repr., Washington DC: Washington National Graphic Society, 1973), 15; C. W. Ceram, The First American: A Story of North American Archaeology (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971), 186–87; Brian Fagen, The Adventure of Archaeology (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1985), 138–39; Philip Kopper, The Smithsonian Book of North American Indians: Before the Coming of the Europeans (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 1986), 70; Jennifer Westwood, ed., The Atlas of Mysterious Places (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987), 117; David Calhoun, ed., 1993 Yearbook of Science and the Future (Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1992), 13; The First Americans (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1992), 115; Duane Champagne, ed., Chronology of Native North American History (New York: Gale Research, 1994), 178; Sally A. Kitt Chappell, Cahokia: Mirror of the Cosmos (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 94; and Peter N. Peregrine, World Prehistory: Two Million Years of Human Life (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003), 11. ↵

- For a discussion of Egan’s panorama, see Angela Miller, “’The Soil of an Unknown America’: New World Lost Empires and the Debate Over Cultural Origins,” American Art 8, nos. 3/4 (Summer/Autumn 1994): 8–27. ↵

- The Minnesota Historical Society contains a panorama by Egan that documents Dickeson’s excavations. See “Notes and Documents: A Mississippi Panorama,” Minnesota History 30 (December 1942): 349–54. This quote derives from a broadside, a large sheet of paper printed on one side that functions as a poster or advertisement. See also Patti Carr Black, Art in Mississippi, 1790–1980, vol. 1 (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 89, and Thomas Ruys Smith, River of Dreams: Imagining the Mississippi Before Mark Twain (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2007), 133–34. ↵

- “Notes and Documents,” 350–51. ↵

- E. H. Davis, a contemporary of Egan and Dickeson, co-authored a book about the mounds of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, and criticized Dickeson’s excavation methods as unscientific and more akin to a picnic than an “accurate investigation,” although modern archaeologists consider him “an innovator in terms of archaeological techniques” and a leader in the field. See E. H. Davis and Ephraim G. Squier, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations (London: Putnam’s American Literary Agency, 1848), 301–3 and Robert E. Bieder, Science Encounters the Indian, 1820–1880: The Early Years of American Ethnology (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986), 116. See also Richard Veit, “A Case of Archaeological Amnesia: A Contextual Biography of Montroville Wilson Dickeson (1810–1882), Early American Archaeologist,” Archaeology of Eastern North America 25 (Fall 1997): 110, for Egan’s use of Dickeson’s field sketches for his composition and for being an innovator in the field, 104. Davis condemned Dickeson’s use of African slaves to dig while he sketched. ↵

- For information about the moundbuilders, see Lynda Norene Shaffer, Native Americans Before 1492: The Moundbuilding Centers of the Eastern Woodlands (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1992). For the citation of Feriday’s plantation, see Veit, “Case,” 97. ↵

- Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, 63. ↵

- Gene Zechmeister, “Jefferson’s Excavation of an Indian Burial Mound,” Thomas Jefferson Monticello, https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/jeffersons-excavation-indian-burial-mound, accessed July 17, 2015. ↵

- The composition conveys this dominant ideology in its progression from a peaceful native family on the right in front of tepees, to white nineteenth-century American men and women dressed in their finery and appreciating the vast wilderness in which other mounts exist, to the labor of African Americans who hold spades and the intellectual white men who hold paper or pencil to sketch, to the dead native peoples’ remains. For an examination of the chronological progression of the panorama, observation of the spade/paper dichotomy, and illustration of the vignette, see Michael A. Chaney, Fugitive Vision: Slave Image and Black Identity in Antebellum Narrative (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 117–18. ↵

- Jarenski, “’Delighted and Instructed,'” 127, 136. ↵

- For information about the relationship between Cherokees and black slaves, see Celia Naylor, African Cherokees in Indian Territory: From Chattel to Citizens (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008). ↵

- For a discussion of Peale’s painting, see Roger B. Stein, “Charles Willson Peale’s Expressive Design: The Artist in His Museum,” in Marianne Doezema and Elizabeth Milroy, ed., Reading American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), especially 68–70. ↵

- Veit, “Case,” 103, 110. Veit suggests that Egan derived his composition from Peale’s Exhumation of the Mastodon,1806. ↵

- For an analysis of Walker’s deconstruction of nineteenth-century panoramas and an analysis of their “imperialist pedagogy,” see Jarenski, “‘Delighted and Instructed,’” 55. ↵

- Kenneth Fletcher, “James Luna,” Smithsonian Magazine (April 2008), http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/james-luna-30545878/?no-ist, accessed 16 December, 2015. I would like to thank the anonymous reader of this essay for the suggestion that I consider his work in relation to Walker’s drawing. ↵

- Ibid. See also Jennifer A. Gonzalez, “James Luna: Artifacts and Fictions,” in Subject to Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 22–62.Ibid. See also Jennifer A. Gonzalez, “James Luna: Artifacts and Fictions,” in Subject to Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 22–62. ↵

- Walker again used the word “subtle” in her project of spring 2014 with its massive, sugar-coated sphinx-like woman: At the behest of Creative Time Kara E. Walker has confected: A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant. See “Creative Time/Presents, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/, accessed July 27, 2015. ↵

- Matthea Harvey, “Kara Walker: An Interview,” Bomb 100 (Summer 2007): 82. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Yasmil Raymond and Rachel Hooper, “Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love,” gallery guide (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2008), 6. ↵

- Harvey, “Kara Walker: An Interview,” 81. Walker elaborated: “Over the years, the persona has shifted here and there to reflect and hold onto this imaginary self of the past and reflect changes in my present circumstances. Like, at one point I added a ‘B’ for my married, hyphenated last name. Then I got rid of the “B.” I am less interested in reinventing that character, because she has to position herself against and sidle up next to white or institutional power in this seductive and cagey way, and I can only do that so often without feeling a little queasy.” ↵

- “Kara Elizabeth Walker, an Emancipated Negress and leader in her Cause” appears in the title of Slavery! Slavery! Presenting a GRAND and LIFELIKE Panoramic Journey into Picturesque Southern Slavery or ‘Life at ‘Ol’ Virginny’s Hole’ (sketches from Plantation Life) See the Peculiar Institution as never before!,1997. “The Young, Self-Taught Genius of the South Kara E. Walker” created the video, Eight Possible Beginnings; or the Creation of Africa-America. A Moving Picture, 2005. ↵

- “The Melodrama of ‘Gone with the Wind,”’ and Saltz, “Kara Walker: Ill-Will and Desire,” 82. ↵

- Consider, for example, the full and equally wordy title of an 1849 panorama: American Panorama of The Nile: Its ancient monuments, its modern scenery, and the varied characteristics of its life on the river, alluvium, and desserts; exhibited in a Grand Panoramic Picture explained in oral lectures and illustrated by a gallery of Egyptian antiquities, mummies, etc. with splendid tableaux of hieroglyphical writing, paintings and sculpture. It too contains nineteenth-century capitalizations, long phrases, awkward punctuated syntax, and abbreviations. ↵

- James Presley Ball’s title is equally wordy: Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States. Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade; of Northern and Southern Cities; of Cotton and Sugar Plantations; of the Mississippi, Ohio and Susquehanna Rivers, Niagara Falls, & C. ↵

- Jarenski, “’Delighted and Instructed,’” 134. ↵

- Harvey, “Kara Walker,” 79. ↵

- The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), 915. ↵

- Ibid., vol. 2 (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1971), 2, 3139. ↵

- Liz Armstrong, “Kara Walker Interviewed by Liz Armstrong,” No Place (Like Home) (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1997), 113. She also wrote in her notes about “the big black mammy” who is “sucked and fucked” as “the ultimate ‘earth mother’ wholly submissive yet defiant.” Kara Walker, Kara Walker (Chicago: Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago, 1997), n.p. ↵

- Harvey, “Kara Walker,” 78. ↵

- Ruth Leys, Trauma: A Genealogy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 2. ↵

- “Artist a Day Challenge No. 17: The Kara Walker Challenge.” ↵

- Richard Meyer uses the phrase about “secrets and structuring absences” that express “both ignorance and knowledge” to address the erasure of homosexuality in twentieth-century American art in Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 26. ↵

About the Author(s): Vivien Green Fryd is Professor of Art History at Vanderbilt University