Heritage and Hate: Teaching Confederate Monuments with Archives

I have been teaching with archives for at least eight years. Initially, my involvement with the University of Georgia Special Collections related to locating historical objects for my material culture students to study firsthand. While most of us think of archives as possessing paper-based artifacts, the library collections on my campus include a lot of wonderful three-dimensional material, from phrenological heads and antique typewriters to football helmets. Only gradually did I begin to include archival documents in my classes. Now, I use them regularly—in person, in digital form, and as printed facsimiles. Even in replica, the students are drawn to the unmediated document as a primary source; for them, it represents the real thing in an era of digital pastiche. Given license to wonder over the material residue left by someone from the past, students usually rise to the occasion—pondering the loop of a letterform, the hesitation of a pen, the crossing out of a mistake. It can be especially useful for first-year students to encounter the archives early in their careers, as they are just learning what the university has to offer. In this essay, I discuss how I built upon my use of archival materials in the classroom after participating in a fellowship program on my campus, how I use the university archives in teaching material culture and museum studies, and then how I focus on an assignment about the Athens Confederate monuments for my first-year seminar called Monuments and Commemoration in America.

Before getting into the details of my teaching, I need to explain a bit more the circumstances found on my campus. The Richard B. Russell Special Collections Libraries at the University of Georgia houses three separate collections: the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, The Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, and the Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection, which is the second-largest media archive in the country. Not all archives equally welcome visitors, so I had always been a little reluctant to bring students, especially new undergraduates, to archival collections, because of concerns about preservation of collections. However, our special collections staff at the University of Georgia have taken an exceptionally generous approach to access—even bringing collections out of the archives and into the public schools as part of their public outreach programs. The belief here is that there is no reason to have a collection that no one uses. In addition to this approach to use, our archivists have actively advocated to expand the definition of archival materials to include three-dimensional artifacts. In just the past decade, the contents of the Georgia State Capitol Museum were added to the university libraries collections. One can argue about what constitutes an archive versus a museum, but the University of Georgia (UGA) has long advocated that archives include artifacts.1

Although I had always been drawn to the archive, my teaching took a decidedly archival turn when I was accepted into the inaugural cohort of Special Collections Fellows at the University of Georgia in 2016. The program was modeled on the Brooklyn Historical Society Teach Archives program and included an interdisciplinary group of faculty members. This was one of the most eye-opening aspects of the fellowship, because it allowed me to learn from others who were doing things with archival material that I had not considered. The group included a faculty member from the theater department who was performing archival material with her classes, another from journalism who was using ephemera to inspire her graphic design students in their selection of poster fonts, and a literary scholar, whose students created a detailed blog based upon their analysis of a medieval manuscript.

My project involved museum studies students, who mined the archive to create a pop-up exhibition as their final exam project. The students developed themes relating to commemoration and war and divided into groups that located and selected artifacts from the collections. They then researched and prepared wall text to introduce their section of the exhibition and label copy for each of the objects. Using vitrines and book cradles from Special Collections, the students assembled an exhibition that occupied our scheduled three-hour exam period. With some advertising and the promise of free snacks, the exhibition attracted visitors from other classes as well as faculty and library staff. The students enjoyed the experience, and other faculty have followed this model with their courses.

I similarly make use of archival objects in my course on American material culture. While most archives are not as rich in artifacts as UGA’s special collections are, many archival collections come to their institutional hosts with objects that can be useful for teaching material culture. For this class, I take students during the first week of classes on what UGA archivist Jill Severn refers to as an “archival first date.” Jill also uses the “first date” concept with faculty when she leads the Special Collections Fellowship workshops. An archival first date at UGA is a group encounter with one or more archival objects (it could be a document, but for my material culture students, we work mostly with three-dimensional objects) during which you interrogate the artifact using description and deduction. The approach will be familiar to anyone who has read Jules Prown’s essays on Material Culture, especially “Mind in Matter”; however, our focus on description is a bit less intensive, as there is a lot of ground to cover in a single class period.2

To aid students’ efforts in examining the object, they are provided with a handout prepared by the Material Culture Caucus of the American Studies Association, called “Twenty Questions to Ask an Object.” During the class, we expect students to work together to become familiar with their object and to make an attempt at understanding what it is. In the last fifteen to twenty minutes of the class, the groups are asked to present their object to the rest of the class. Ideally, the first date is followed by a second archival session the following week, which reveals more about each of the objects that the students examined. We then look closely at the catalogue record for the object to discuss issues of provenance and collecting habits, as well as to give context for the object within the archival collections. This typically segues to a discussion of search strategies for locating additional objects. In the process, students learn about their object, the university collections, and how to use the online catalogue. What they also take away is a rare in-class experience to handle artifacts that they cannot get with other collections on campus. No matter how accommodating our art museum is, they are simply not able to offer this kind of direct engagement with an object.

A final archival teaching project, the one I really want to focus on here, involves the teaching of Civil War monuments in the South. I often teach the history of a Confederate monument (fig. 1) that stands just outside the Athens campus’s iconic arch on the main thoroughfare. Situated in a traffic median with cars whizzing by on either side of the monument, the monument is extremely difficult to examine with a class. Nonetheless, we visit the site—standing at a safe distance from the street. This visit prompts questions about the monument’s history, origins, and purpose.

Our next step includes the use of an interpretive template provided by the Atlanta History Center website. The template asks questions about the organization that spearheaded the building of the monument, the dedication ceremony at its unveiling, and any inscriptions on the work. In order to answer these questions, we look to the monument itself and I have students read an article about the monument from 1956 by UGA professor (and white supremacist) E. Merton Coulter.3 From Coulter, the students learn that the monument was built in 1872, through the efforts of the Athens Ladies Memorial Association, which was founded in 1866. Coulter’s writing is clear and his research is thorough, making use of newspaper accounts and archival sources, but his cheerful embrace of the Lost Cause, an interpretation of the Civil War that erases slavery as its cause and valorizes the Confederacy, is disturbing. My students hardly notice, requiring some structured discussion to consider what is said about the monument and what is not. For example, when Coulter writes that The Athens Thespian Club put on “a humorous performance” of “‘Box and Cox’ l’Africane” [sic], the students tend to miss that this is a reference to a minstrel show, even though Coulter goes on to quote the following praise of the performance in a local newspaper: “Our people do not seem to appreciate the drama but some of them are ‘great’ on monkey shows.”4 It is not that the students cannot see what this means, but between a lack of familiarity with the past, including general ignorance of minstrelsy, and a desire not to look too closely at overt racism of this type, they often rush past such statements to grasp at Coulter’s praise of the Athens Ladies Association’s hard work in spearheading the monument project and his repeated references to the valor of the dead and their noble cause.

From Coulter, we move to archival sources, including a few documents that Coulter collected for his article. There are relatively few documents that can speak to the history of the monument, which is both good and bad in terms of teaching. There is little to wade through, so students can stay on task, but the documents we have leave many questions unanswered. Students are encouraged to raise any and all questions that they have from the outset, as the contents of a nineteenth-century document are not always clear to a generation raised on social media. We begin with the founding document from the Ladies Memorial Association in Athens, a short, unsigned, handwritten text that tells us nothing about the Ladies members—it simply lists the bylaws of the organization.5

The first obstacle is in deciphering cursive writing, which many students no longer learn how to read or write. Yet, I learned from my colleague working on medieval manuscripts, who found that some of her students excelled at transcribing texts and others did not, to simply let the students sort out their comfort with this task. Allowing for a differentiation of skills can work well in a group setting, as long as everyone has a role to play. So I let the students who are good at deciphering the text do that for everyone else as long as the rest of the students are thinking about the content. In addition to this text, there are also a few broadsides relating to fundraising fairs hosted by the Ladies Association. The documents leave much unanswered but offer a solid case study for early postwar monument building in the South. There are few clearly provocative statements regarding race or slavery, including the Ladies Association’s declaration that they wanted a monument that was “as white and spotless, as the cause for which they died was pure and holy.” We parse the language used in these texts and the notable absence of any mention of slavery.

Students typically walk away confused—trusting a bit too much in the Ladies’ statements about honor and their duty to the dead. I try not to be too skeptical of the Ladies but push around the edges to get the students to read more deeply into the documents. For instance, the third bylaw in the document indicates that any member who misses a meeting would be fined one dollar, a seemingly small sum that can be put in perspective when we note the contributions made to the Association to build the monument were often in small amounts. That the ladies met the first Tuesday of every month at ten in the morning in Town Hall adds to the picture of well-off white women making use of town facilities to plan a monument to the Confederacy. The document also notes the involvement of many powerful men, challenging the long-held beliefs of historians that Confederate monuments were spearheaded by women. During Reconstruction, when the Athens monument was built, women provided cover, but men provided the funding, and the Ladies expected “every truehearted Southern man” to “give liberally of his means and his talents” to aid in building the monument.

Gender is, of course, central to our in-class discussions of the monument. One question that usually comes up is, “Why are the Ladies anonymous?” It is possible to determine who some of them were, but only two names appear on the broadside for “A Grand Fair”: C. Barrow and L. Rutherford.6 Both names hail from the leading families in Athens, names that are still enshrined in the landscape in streets and elementary schools today. L. Rutherford was Laura Rutherford (née Cobb), mother to Mildred Rutherford, who became an important promoter of the Lost Cause as the historian general for the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

None of the Ladies Association members spoke at the dedication, with the primary oration given by Alexander Smith Erwin, a Confederate veteran and judge. A broadside of his lengthy speech makes tedious reading but is a great example of the Lost Cause at work. Slavery goes unmentioned. Erwin’s speech dwells upon noble ideals, patriotism, and honor. He valorizes the Southern cause as motivated by “love of country,” a curious phrase to describe the acts of secessionists—and my students argue over what country the text is referring to. Erwin’s speech echoes the language on the monument itself.7

Another thing that becomes very clear as we examine historic newspapers of Athens, which have been helpfully digitized by the Digital Library of Georgia, is that while this is not a campus monument, university actors were very active in the project, and the campus was used for fundraisers hosted by the ladies and students. Turning to vintage postcards in the library collections, we also see how the monument migrated from its original site to its current location just outside the university entrance. This is important because my students often fall back on the facile belief that monuments should stay where they are because they have always been there, or that to move them somehow changes history.

After lengthy discussion, teasing out information from the documents, there are still many questions remaining, but playing historian is only part of the class, so I ask the students to decide how they would handle the monument if they were “in charge.” The answers vary, but most see the problem as complicated, which is actually what I hope to achieve, since they usually feel at the beginning of the course that these monuments should stay put because they represent Southern heritage.

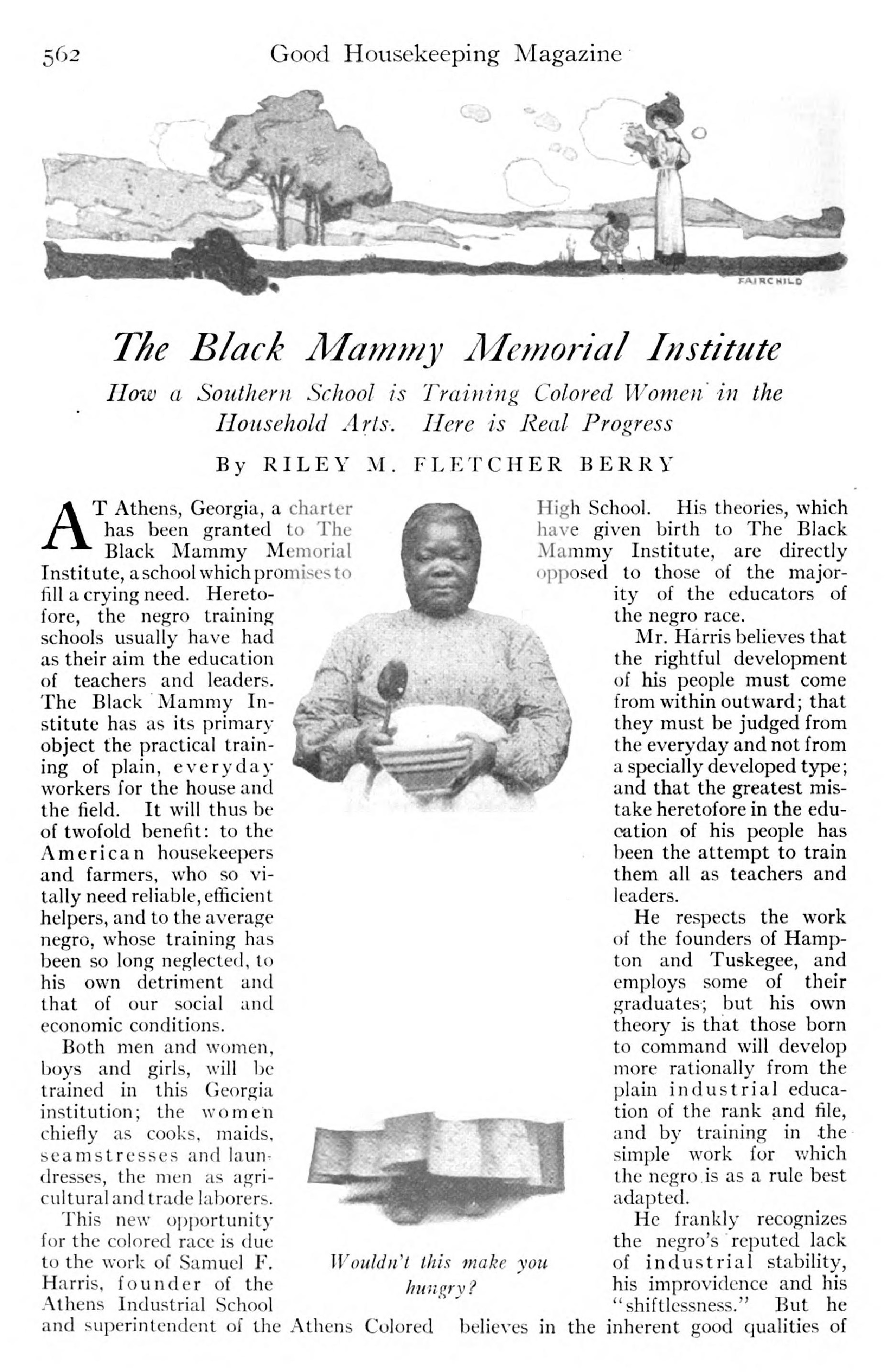

And then I show them the prospectus for the Athens Black Mammy Memorial (fig. 2), from around 1910.8 This was a proposal for a school intended to train “the average Negro” for service positions in the South. The prospectus is not shy about making a case that blacks needed to learn how to be better servants, just like “in the good old days” of slavery. This is explicitly stated in the school promotional literature, which was also excerpted in an article on the school in Good Housekeeping that reads: “This new school represents the South and suggests the special training given the negroes of the old regime, by the best class of Southern slave-holders.”9 My students get uncomfortable in ways that they are not when we talk about the Confederate Monument. The prospectus is overtly racist even in its celebratory descriptions of the faithful mammy that the school commemorates. Looking through the document we see the same family names among the trustees of the Mammy Memorial as those who contributed to the Confederate Monument. And the university was also deeply involved in this project. To hammer home this connection, a photograph of the Confederate memorial appears on the final page of the prospectus.

The Mammy Memorial does not exist, but documents help bring to life the ways that Athenians felt about slavery and commemoration that would be harder to get at without these texts. When confronted with clear racism, it is harder for the students to justify the intentions of these Southern monument builders as being motivated purely by love of their heritage. This connection is something that I would struggle to convey at a Southern school where students’ thoughts about the Confederacy are shaped by the continuing regional embrace of the Lost Cause and by familial notions of heritage. In spite of the lingering potency of the Lost Cause, most students like to believe that they are racially inclusive and see the absence of slavery in the Confederate Monument inscriptions as evidence that the monument is about honor and heritage, and not as a sign of white supremacy. The Black Mammy Memorial prospectus does work that I could never do through other means—it shows how white elites in Athens, the same class as those who erected the Confederate Monument, felt about African Americans. Not just that they personally felt that blacks were inferior, but also that these whites wanted to relegate African Americans to menial positions of continued servitude in white households. And more, that they continued to honor the institution of slavery by looking to the “best class of Southern slave-holders” as their model. The document shocks and offends, but it also helps students understand what white supremacy means and that it can take different forms: it may be found in a both Confederate monument and a Mammy Memorial.

Cite this article: Akela Reason, “Heritage and Hate: Teaching Confederate Monuments with Archives,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2216.

PDF: Reason, Heritage and Hate

Notes

- Jill Robin Severn, “Adventures in the Third Dimension: Reenvisioning the Place of Artifacts in Archives,” in Karen Dawley Paul, Glenn R. Gray, and Rebecca Johnson Melvin, eds. An American Political Archives Reader (Lathan, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009), 221–33. ↵

- Jules David Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” Winterthur Portfolio 17 (Spring 1982): 1–19. ↵

- E. Merton Coulter, “The Confederate Monument in Athens, Georgia,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 40 (September 1956): 230–47. ↵

- Coulter, “The Confederate Monument in Athens, Georgia,” 237. ↵

- Athens Ladies Memorial Association Collection, Hargrett Library, University of Georgia. ↵

- E. Merton Coulter Collection, Hargrett Library, University of Georgia. ↵

- Memorial Address, Delivered on the Dedication of the Monument to the Confederate Dead of Clarke County, Athens. June 3, 1872, by A. S. Erwin, Broadside Collection, Hargrett Library, University of Georgia. ↵

- “The Black Mammy Memorial,” Hargrett Library, University of Georgia. ↵

- Riley M. Fletcher Berry, “The Black Mammy Memorial Institute: How a Southern School is Training Colored Women in the Household Art: Here is Real Progress.” Good Housekeeping Magazine 53 (July 1911): 563. ↵

About the Author(s): Akela Reason is Associate Professor of History at the University of Georgia