As part of the History Project, I assist others in using archival materials to answer questions and conduct research. People who use the archives are undergraduates, grad students, staff, faculty, administrators, scholars from other institutions, and the general public.

Email & phone inquiries are the most popular methods of contacting me but the occasional letter or drop-in happens as well.

Using the archives and asking questions are free of charge and open to anyone. Some questions are easy to answer while others require time to review materials and dig a little deeper. And, sometimes a definitive answer cannot be found (although hopefully enough information can be obtained to at least support a conclusion).

A few examples of recent reference questions and the answers are below. Perhaps you where wondering the same thing. . .

Question: Could you verify for me that Powell Hall could have been a place where families might have stayed when they had family members in the hospital?

Answer: Yes. Powell Hall served a variety of purposes from its dedication in 1933 to its demolition in 1981. Powell Hall was primarily, and is most known for being, a residence hall for nursing students. During its last two decades it also provided dormitory housing for women from across campus, housed administrative office space for the School of Public Health, and was used as a resting space for on-call hospital staff. In the 1970s, families who traveled to the Twin Cities to be close to a family member at the University Hospitals had the opportunity to stay at the “Powell Hall motel as a convenience for patients and their relatives.”

Answer: Yes. Powell Hall served a variety of purposes from its dedication in 1933 to its demolition in 1981. Powell Hall was primarily, and is most known for being, a residence hall for nursing students. During its last two decades it also provided dormitory housing for women from across campus, housed administrative office space for the School of Public Health, and was used as a resting space for on-call hospital staff. In the 1970s, families who traveled to the Twin Cities to be close to a family member at the University Hospitals had the opportunity to stay at the “Powell Hall motel as a convenience for patients and their relatives.”

Question: I am looking for information about the establishment of a Learning Resource Center for the health sciences in the 1970s. It was one of the first in the nation to be housed within a biomedical library.

Answer: Yes, there is information related to the establishment of the Learning Resource Center (originally known as the Instructional Resource Center) for the health sciences, the precursor to the AHC Learning Commons, at the archives. In 1968 a subcommittee for long-range planning for the health sciences investigated the programmatic & spaces needs of a learning resource center. In 1970 a prototype center was established in Diehl Hall by the Medical School in conjunction with the Bio-Medical Library. A sampling of documentation related to this subcommittee originally chaired by Dr. Ramon M. Fusaro is available in the digital archives.

Answer: Yes, there is information related to the establishment of the Learning Resource Center (originally known as the Instructional Resource Center) for the health sciences, the precursor to the AHC Learning Commons, at the archives. In 1968 a subcommittee for long-range planning for the health sciences investigated the programmatic & spaces needs of a learning resource center. In 1970 a prototype center was established in Diehl Hall by the Medical School in conjunction with the Bio-Medical Library. A sampling of documentation related to this subcommittee originally chaired by Dr. Ramon M. Fusaro is available in the digital archives.

Question: Where were the original operating rooms in Elliot Memorial Hospital?

Answer: The exact answer to this question still eludes me but trying to answer it has been a very enjoyable process. Elliot Memorial Hospital was dedicated in September of 1911 as the first university teaching hospital. In subsequent years it was expanded to include the Todd and Christian wings and the Eustis Children’s Hospital. In 1954 this U-shaped configuration served as the east, south, and west sides of the new Mayo Memorial Building.

Answer: The exact answer to this question still eludes me but trying to answer it has been a very enjoyable process. Elliot Memorial Hospital was dedicated in September of 1911 as the first university teaching hospital. In subsequent years it was expanded to include the Todd and Christian wings and the Eustis Children’s Hospital. In 1954 this U-shaped configuration served as the east, south, and west sides of the new Mayo Memorial Building.

I have looked at original blueprints from 1911 although they mostly depict external details, reviewed floor plans from the late 1950s after the completion of the Mayo Memorial Hospital, and walked the halls. I’ve spoken with faculty and staff who have some insight but to no avail. Although I have not exhausted my sources, evidence indicates space on the 5th and 6th floors could have contained an observational gallery and sky lights that would have overseen the surgical room. Hopefully more on this to come.

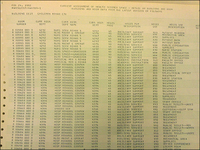

Question: I was told that the archives has faculty lists for the Urology service–right? I don’t need salary or any other info, only a list of those with title of assistant professor or higher after 1966.

Answer: There are a variety of sources to try and determine faculty lists, however, one of the easiest sources to use are the course catalogs and bulletins for undergraduate, graduate, professional, and non-degree programs. Within the description of each school and program there is almost always a list of affiliated faculty by their rank. Most bulletins were published on a biannual basis and may miss a name or two but are generally considered reliable in their accuracy. The bulletins date from 1871 to the present. A print set is available at the University Archives. Most of the bulletins from 1871 through the 1940s are also available online.

Have a question you’d like to ask? Have a better answer to any of the above? Please, feel free to contact me.

The strength of one’s bite and the force used to chew food appear to have intrigued dental students for centuries. The earliest investigation of jaw strength on record dates to 1681 in Rome by Professor Giovanni Borelli of the Jesuit College (see picture at right). The value of the early studies on bite force and jaw muscle strength was mainly in satisfying curiosity, however later interest existed in the effect of functional demands on tissue health and development.

The strength of one’s bite and the force used to chew food appear to have intrigued dental students for centuries. The earliest investigation of jaw strength on record dates to 1681 in Rome by Professor Giovanni Borelli of the Jesuit College (see picture at right). The value of the early studies on bite force and jaw muscle strength was mainly in satisfying curiosity, however later interest existed in the effect of functional demands on tissue health and development. In 1936, the University of Minnesota’s School of Dentistry determined that the principle difficulty encountered by researchers studying the muscles of mastication was the lack of an instrument to accurately measure the pressure exerted by the jaws. Along with the University of Minnesota Scientific Instrument Shop, the School of Dentistry developed the “Gnathodynamometer of the School of Dentistry, University of Minnesota”. Would you bite on this for science?

In 1936, the University of Minnesota’s School of Dentistry determined that the principle difficulty encountered by researchers studying the muscles of mastication was the lack of an instrument to accurately measure the pressure exerted by the jaws. Along with the University of Minnesota Scientific Instrument Shop, the School of Dentistry developed the “Gnathodynamometer of the School of Dentistry, University of Minnesota”. Would you bite on this for science?